Ninth Circuit Tells Trademark Owners to Stop Suing Over Competitive Keyword Ads–Lerner & Rowe v. Brown Engstrand

This is a major ruling validating the legitimacy of competitive keyword advertising, which occurs when an advertiser purchases and displays ads triggered in response to third-party trademarks. Recently, the “Second Circuit Tells Trademark Owners to Stop Suing Over Competitive Keyword Advertising.” Now, the Ninth Circuit similarly urges trademark owners to quit it. Will they get the message?

* * *

Background

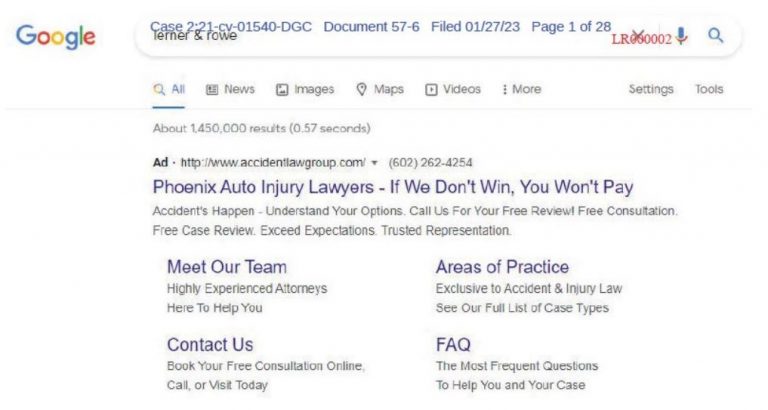

Lerner and Rowe is an Arizona law firm. It has spent $100M on advertising. Brown Engstrand is a start-up rival law firm (operating under the brand “Accident Law Group”). The rival bought competitive keyword ads (the court uses the term “conquesting,” which I objected to here) but didn’t include the third-party trademark in the ad copy. Here’s an example:

Competitive keyword advertising by law firms has been a source of trouble for years. I wrote a whole paper just about that in 2016–we’re still discussing it 8 years later 🙄. Many firms do it–“Lerner & Rowe has engaged in conquesting in other contexts,” so, um…unclean hands? The trademark owner sued the advertiser for trademark infringement and lost in the district court. Prior blog post on the district court ruling.

The Panel Opinion

The court says that Lerner & Rowe didn’t establish a likelihood of consumer confusion per the expedited 4-factor test for keyword advertising articulated in the Network Automation case. Lerner & Rowe invoked the initial interest confusion doctrine, but as the Network Automation case explained, IIC just merges back into the likelihood of confusion analysis and does not create any workaround or bypass.

Mark Strength: The court says the mark is strong, in part evidenced by the fact the plaintiff law firm has over 100k clients.

Actual Confusion: Some data about the advertiser’s campaign:

- The advertiser’s ads showed up in response to the “Lerner & Rowe” keyword trigger 109,322 times.

- Those ads produced 7,452 clicks (6.82% CTR–overall, pretty good).

- 236 incidents that Lerner & Rowe claimed were evidence of actual confusion (less than 0.25% of the total ad exposures). The court doesn’t necessarily believe that all 236 incidents actually demonstrated consumer confusion, but the court assumes they are. The court also observes that normally anecdotes of actual consumer confusion lack a “denominator” of the number of total consumer contacts, but both numerator and denominator data is available here.

Based on the ~0.2% confusion rate, the court says: “No reasonable jury would conclude that this percentage is anything but de minimis and fails to support a finding of likelihood of confusion….the evidence Lerner & Rowe has presented is so slight it may as well have presented none at all” (ouch). Because Lerner & Rowe brought in such weak sauce, the court says: “the nature of the actual confusion evidence paints a picture that affirmatively contradicts Lerner & Rowe’s assertions that ALG’s advertisements were likely to confuse an appreciable number of consumers, compelling us to conclude that this factor should weigh substantially in favor of ALG.” (OUCH).

Basically, this is the court’s plea to trademark owners suing over competitive keyword advertising to DO BETTER…if they can, but the data probably means they can’t…

Consumer Care. Check out this passage 🤯:

Google’s search engine is so ubiquitous that we can be confident that the reasonably prudent online shopper is familiar with its layout and function, knows that it orders results based on relevance to the search term, and understands that it produces sponsored links along with organic search results. Moreover, in this case, the relevant consumers specifically typed in “Lerner & Rowe” as a search term, suggesting that they would be even more discerning of the results they received. Therefore, because this case involves shopping on Google by using the precise trademark at issue, this factor weighs in favor of ALG.

Look how far we’ve come in the last 15-20 years. Back in the old days, judges were baffled by keyword advertising. Now, they’re like “it’s so obvious…DUH!”

To be fair, the empirical data does not universally back up this judicial intuition. Consumers are still confused about a lot of things online. But the court basically says that if a consumer searches for the trademark, they will be MORE CAREFUL to actually get the trademark owner. This is a 180 from the old days, when judges assumed that any consumer searching for the trademark was unshakably brand-loyal–except in the face of an interloper competitor’s ad, which would instantly dissolve their loyalty and “divert” them to some unwanted outcome.

Ad Labeling. Lerner & Rowe provided three screenshots of searches for “Lerner & Rowe.” Two of them displayed results for Lerner & Rowe. For these, the court says: “we find it difficult to believe that consumers searching for the phrase ‘Lerner & Rowe’ would not choose to click on the link that matches their search query word for word.” Wow, talk about appellate judges making up facts. Consumer search behavior has been studied extensively, and consumers in fact click on non-identical searches all of the time.

The court doesn’t care if the advertiser’s ad appears above results for the trademark owner: “We think that reasonably prudent consumers shopping on Google would be accustomed to scrolling past advertisements at the top of a list of search results to find the organic result relevant to their query.” More manufactured empiricism.

The court says that if the trademark owner’s results appear anywhere in the search results, that dispels any consumer confusion (the search results “page invariably contains a result for Lerner & Rowe that includes the precise search term at issue, dispelling any confusion ALG’s advertisements might cause”–the “invariably” is more manufactured empiricism).

One of Lerner & Rowe’s screenshot showed search results displaying the rival ad and no result for Lerner & Rowe. The court says that even if a Lerner & Rowe result didn’t show up anywhere in the search results, it wouldn’t matter. The ad copy isn’t confusing enough to “reasonably prudent online shoppers into unwittingly clicking on them in search of Lerner & Rowe’s website.” Furthermore, in a mild surprise, the court blesses Google’s “ad” label: “the bolded “Ad” designation next to each of ALG’s advertisements sufficiently distinguishes ALG’s advertisements from the search’s organic results.” (There are a lot of government agencies and consumer advocates who would vociferously complain that Google’s current “ad” label is too obscure).

Other Sleekcraft Factors. The court goes beyond the 4-factor Network Automation test and acknowledges the other factors, but it dismisses them:

- Proximity of Goods. Not important in keyword ad cases.

- Marketing Channels. The court says “This factor might be relevant if ALG’s advertisements appeared on a lesser-known or product-specific search engine.” Huh? In any case, Lerner & Rowe cited a case from 2000 on this factor, and the court swats it away as outdated (“that may have been true over twenty years ago when internet advertising was new”). 💥

- Mark Similarity. The defendant displayed its own trademark in the ad copy, not the plaintiff’s, so the marks were dissimilar.

- Intent. The trademark owner “failed to distinguish between an intent to deceive and an intent to compete.” PREACH.

- Product Line Expansion. Not important in keyword ad cases.

The court concludes:

The district court was correct to conclude that this is one of the rare trademark infringement cases susceptible to summary judgment. The generally sophisticated nature of online shoppers, the evidence demonstrating that there is not an appreciable number of consumers who would find ALG’s use of the mark confusing, and the clarity of Google’s search results pages, convince us that ALG’s use of the “Lerner & Rowe” mark is not likely to cause consumer confusion.

I’m not sure why the court says that summary judgment is rare in trademark cases. Still, the implications are clear: Lerner & Rowe brought weak sauce to court and got the inevitable judicial roasting. 🔥

The Concurrence

In her concurrence, Judge Desai would have gone further to say that competitive keyword advertising isn’t a trademark use in commerce. 😲 On the one hand, I don’t relish the bruising battles over the Lanham Act’s confusing treatment of the “use in commerce” concept. On the other hand, the lack of “use of commerce” was always the appropriate path to resolve competitive keyword ad cases. Judge Desai says that Network Automation’s ruling on the use in commerce question should be reconsidered: “I am not convinced that we got it right or that our holding withstands the test of time and recent advancements in technology.” 💥

Judge Desai says in Network Automation, “we provided no analysis to support this holding, and we relied on cases with meaningfully different facts.” For example, the Rescuecom case involved keyword ad selling, not buying, and Google had to display the trademark to make its sales.

Keyword metatags are also distinguishable: “incorporating metatags consisting of a competitor’s trademark into a website code is comparable to displaying or presenting a mark….Even if metatags do not involve an external display, they are functionally equivalent to “affixing” the competitor’s mark to the product—a defendant affixes the competitor’s mark to its website through its code to gain the benefits of the mark.” Ugh, seriously, nooooo…. Keyword metatags are the trees that fall in the forest that no one hears. They should be legally irrelevant. Still, Judge Desai gets back on track when she says: “keyword bidding does not require the defendant to display or affix a mark—internally or externally—in the advertising of its services.” She says if anyone displays the mark, it’s Google, not the advertiser. Thus, “ALG’s actions look nothing like the ordinary case [of trademark infringement]. Indeed, ALG never presented Lerner & Rowe’s marks to the consumer on the other end of the search engine—or to any consumer at all.”

Judge Desai closes out with some truth bombs:

- “We should reconsider our holding in Network Automation en banc”

- “Network Automation’s holding is unsupported by existing case law”

- Noting how Network Automation’s bastardization of the standard Sleekcraft test basically turns on ad labeling: “Rather than continue relying on a nearly dispositive factor created exclusively for this context with little guidance, we should consider correcting our precedent.”

- “given the predominance of the internet in our lives, this type of advertising has become commonplace. Scrolling through sponsored ads at the top of a results page is often the rule—not the exception—when using a search engine.”

- “Consumers likely understand that, even when they search for a trademarked term, the sponsored results may not be associated with that trademark.”

🙏🙏🙏 to Judge Desai for speaking out.

Implications

Biden Appointees Bring Fresh Perspectives. The majority opinion was written by Judge de Alba and the concurrence was from Judge Desai. They share several key demographics: mid-40s, women of color, Biden appointees. What a breath of fresh air they bring compared to these venerable questions that have vexed the older generation of judges. I love to see it.

Who’s Up for Another Round of Tussling Over “Use in Commerce”??? Judge Desai’s concurrence creates a dilemma for Lerner & Rowe deciding if it should seek en banc review. Doing so could prompt the Ninth Circuit to open up the “use in commerce” question, which gives it another way it could lose. (And other trademark owners would be really bummed if Lerner & Rowe messes up the “use in commerce” doctrine for all of them too). At minimum, if Lerner & Rowe seeks en banc review, us OG Internet trademark nerds will take advantage of the opportunity to relitigate the “use in commerce” topic. You’ve been warned.

STOP. SUING. OVER. COMPETITIVE. KEYWORD. ADS. This opinion is categorically bad news for trademark owners hoping to sue over competitive keyword advertising. Multiple aspects of the opinion create seemingly insurmountable barriers for plaintiffs:

- there is no initial interest confusion bypass

- Google’s ad labeling is good enough to swing this factor in favor of the advertising

- the advertiser can win even if it shows up in the search results above or instead of the trademark owner

- if a consumer searches for a trademark, the purchaser care factor will weigh in favor of the defense

- 236 incidents of (alleged) actual confusion aren’t enough to swing the factor towards the trademark owner

- the court can compute actual confusion using either of the following two formulas: [number of alleged incidents of actual confusion]/[total ad impressions] OR [number of ad clicks]/[total ad impressions] (the latter formula is the clickthrough rate or CTR). If neither formula produces a result of over 10%, then the court should treat the alleged consumer confusion rate as de minimis and pro-defendant. But it is almost impossible for either formula to get close to 10%, so these formulas will ALWAYS favor defendants. This is not a new outcome–the Tenth Circuit adopted the CTR standard in 1-800 Contacts v. Lens.com over a decade ago–but the Ninth Circuit’s embrace it makes it likely that other courts around the nation will follow this.

Trademark owners have no way to navigate around this impenetrable doctrinal wall. The court is telling trademark owners, as plain as it can, to stop bringing competitive keyword advertising lawsuits.

The only qualification was the panel’s indication that summary judgment should be rare in trademark cases. This might embolden trademark owners to think that they should definitely survive a motion to dismiss for their competitive keyword ad cases and get into expensive discovery, including making invasive document requests to a competitor and possibly goading the advertiser-defendant to waste money on one or more expensive consumer surveys to prepare for summary judgment. Thus, surviving a motion to dismiss could enable pernicious trademark owner lawfare, and this gives trademark owners some incentives to bring doomed cases that the defendant will capitulate before summary judgment. Given the relatively low profitability of most competitive keyword advertising campaigns, the lawfare risks could discourage advertisers engaging in legitimate behavior. I hope lower courts will aggressively gatekeep trademark owner lawsuits over competitive keyword advertising to reduce this lawfare risk. Lower courts should routinely save everyone some money and end competitive keyword advertising cases before discovery.

Is This Opinion Good or Bad News for Google? Google was a major player in this lawsuit by proxy. Among other mission-critical issues for Google, the court opined on its “Ad” label and the legal efficacy of restricting third-party trademarks in ad copy,. The concurrence also opined on whether or not keyword ad sales by Google constitute a use in commerce.

This opinion was generally good news for Google. The court blessed some of its key practices, and anything that gives more legal breathing room to advertisers to do more advertising is an economic win for Google. For Google, the only dark cloud was the concurrence’s effort to hold that competitive keyword advertisers are categorically not making a trademark use in commerce, but keyword ad sellers are. This could prime trademark owners to reignite the litigation crusade against Google (there were over 2 dozen lawsuits 15 years ago) and then pursue their competitors as contributory trademark infringers. So much time and money was wasted on the trademark battles over keyword ad sales back in the old days, and it would break my heart if we do all of that over again.

Appellate Empiricism. Appellate courts typically should not make factual findings, but that rule is routinely honored in the breach in trademark law cases, where appellate judges all the time make assumptions about consumer behavior that have little or no empirical grounding.

This panel went ham as a empirical fact-finder. For example, the panel opinion says:

- “Google’s search engine is so ubiquitous that we can be confident that the reasonably prudent online shopper is familiar with its layout and function, knows that it orders results based on relevance to the search term, and understands that it produces sponsored links along with organic search results”

- “the relevant consumers specifically typed in “Lerner & Rowe” as a search term, suggesting that they would be even more discerning of the results they received”

- “we find it difficult to believe that consumers searching for the phrase ‘Lerner & Rowe’ would not choose to click on the link that matches their search query word for word”

- “We think that reasonably prudent consumers shopping on Google would be accustomed to scrolling past advertisements at the top of a list of search results to find the organic result relevant to their query”

The concurrence adds:

- “Consumers likely understand that, even when they search for a trademarked term, the sponsored results may not be associated with that trademark”

Overall, I’m happy to see the Ninth Circuit push back against bogus competitive keyword advertising lawsuits, but I hate that the panel had to make assumptions about consumer behavior to get there. Among other problems, judges are highly atypical of the average consumer, and judges are in a terrible position to extrapolate how other consumers navigate the marketplace (or, in this context, navigate Google search results pages).

To be fair, trademark owners routinely get the benefit of judicial assumptions. Indeed, pro-plaintiff doctrines like “initial interest confusion” exist solely because judges made unsupportable assumptions about consumer behavior. (Dilution is another concept that isn’t empirically supportable, but we blame the legislatures for that). The solution isn’t for judges to make counterbalancing pro-defense assumptions. Instead, judges need to demand greater empirical rigor from the litigants to justify their positions; failing that, consult the empirical literature; and failing that, not make assumptions.

The Overlay of Legal Ethics Rules. Competitive keyword advertising by lawyers is different from most other industry segments, because lawyers must also comply with their ethics rules in addition to trademark law. Unfortunately, some regressive state bars have taken the position that the ethics rules categorically ban lawyers’ competitive keyword advertising, even if there’s no evidence of any IP violation or any consumer deception or harm. These states have created a mutant species of IP law disconnected from both trademark law or false advertising law; and this mutant IP comes from an unelected group, not a legislature. The result of these laws is to tamp down on competition between lawyers–nothing new for state bars, but still a condemnable development.

As the courts continue to eviscerate the legal challenges to competitive keyword advertising, I hope the regressive state bars will walk back their bans. Banning lawyers from engaging in competitive keyword ads is completely indefensible policy. Or perhaps an advertising lawyer will fight back in court and establish that such bans violate lawyers’ First Amendment rights to advertise.

Case Citation: Lerner & Rowe, PC v. Brown, Engstrand & Shely, LLC, 2024 WL 4537915 (9th Cir. Oct. 22, 2024)

BONUS: Blue Sky Endeavors LLC v. Henderson County Hospital Corp., 2024 WL 4539114 (W.D.N.C. Oct. 21, 2024):

The Plaintiffs have presented evidence that after Pardee Hospital began using the Pardee Mark, LFM received multiple phone calls from people who got LFM and Pardee Hospital “mixed up.” This evidence, though, is simply “initial interest confusion” because any confusion was easily “dispelled” before anyone was served by the wrong provider.

Actually, this is just evidence of actual confusion, not “initial interest confusion,” and I don’t believe any other court has used the IIC term in this way. But no one has any idea what IIC means, so why not create more new meanings? 😑

More Posts About Keyword Advertising

* Second Circuit Tells Trademark Owners to Stop Suing Over Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Catching Up on Two Keyword Ad Cases

* Competitor Isn’t Responsible for Google Knowledge Panel’s Contents–International Star Registry v. RGIFTS

* TIL: “Texas Tamale” Is an Enforceable Trademark–Texas Tamale v. CPUSA2

* Internal Search Results Aren’t Trademark Infringing–PEM v. Peninsula

* When Do Inbound Call Logs Show Consumer Confusion?–Adler v McNeil

* Court Denies Injunction in Competitive Keyword Ad Lawsuit–Nursing CE Central v. Colibri

* Competitive Keyword Ad Lawsuit Fails…Despite 236 Potentially Confused Customers–Lerner & Rowe v. Brown Engstrand

* More on Law Firms and Competitive Keyword Ads–Nicolet Law v. Bye, Goff

* Yet More Evidence That Keyword Advertising Lawsuits Are Stupid–Porta-Fab v. Allied Modular

* Griper’s Keyword Ads May Constitute False Advertising (Huh?)–LoanStreet v. Troia

* Trademark Owner Fucks Around With Keyword Ad Case & Finds Out–Las Vegas Skydiving v. Groupon

* 1-800 Contacts Loses YET ANOTHER Trademark Lawsuit Over Competitive Keyword Ads–1-800 Contacts v. Warby Parker

* Court Dismisses Trademark Claims Over Internal Search Results–Las Vegas Skydiving v. Groupon

* Georgia Supreme Court Blesses Google’s Keyword Ad Sales–Edible IP v. Google

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Claim Fails–Reflex Media v. Luxy

* Think Keyword Metatags Are Dead? They Are (Except in Court)–Reflex v. Luxy

* Fifth Circuit Says Keyword Ads Could Contribute to Initial Interest Confusion (UGH)–Adler v. McNeil

* Google’s Search Disambiguation Doesn’t Create Initial Interest Confusion–Aliign v. lululemon

* Ohio Bans Competitive Keyword Advertising by Lawyers

* Want to Engage in Anti-Competitive Trademark Bullying? Second Circuit Says: Great, Have a Nice Day!–1-800 Contacts v. FTC

* Selling Keyword Ads Isn’t Theft or Conversion–Edible IP v. Google

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Still Isn’t Trademark Infringement, Unless…. –Adler v. Reyes & Adler v. McNeil

* Three Keyword Advertising Decisions in a Week, and the Trademark Owners Lost Them All

* Competitor Gets Pyrrhic Victory in False Advertising Suit Over Search Ads–Harbor Breeze v. Newport Fishing

* IP/Internet/Antitrust Professor Amicus Brief in 1-800 Contacts v. FTC

* New Jersey Attorney Ethics Opinion Blesses Competitive Keyword Advertising (…or Does It?)

* Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Dr. Greenberg v. Perfect Body Image

* The Florida Bar Regulates, But Doesn’t Ban, Competitive Keyword Ads

* Rounding Up Three Recent Keyword Advertising Cases–Comphy v. Amazon & More

* Do Adjacent Organic Search Results Constitute Trademark Infringement? Of Course Not…But…–America CAN! v. CDF

* The Ongoing Saga of the Florida Bar’s Angst About Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Your Periodic Reminder That Keyword Ad Lawsuits Are Stupid–Passport Health v. Avance

* Restricting Competitive Keyword Ads Is Anti-Competitive–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* Another Failed Trademark Suit Over Competitive Keyword Advertising–JIVE v. Wine Racks America

* Negative Keywords Help Defeat Preliminary Injunction–DealDash v. ContextLogic

* The Florida Bar and Competitive Keyword Advertising: A Tragicomedy (in 3 Parts)

* Another Court Says Competitive Keyword Advertising Doesn’t Cause Confusion

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Doesn’t Show Bad Intent–ONEpul v. BagSpot

* Brief Roundup of Three Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Developments

* Interesting Tidbits From FTC’s Antitrust Win Against 1-800 Contacts’ Keyword Ad Restrictions

* 1-800 Contacts Charges Higher Prices Than Its Online Competitors, But They Are OK With That–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* FTC Explains Why It Thinks 1-800 Contacts’ Keyword Ad Settlements Were Anti-Competitive–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* Amazon Defeats Lawsuit Over Its Keyword Ad Purchases–Lasoff v. Amazon

* More Evidence Why Keyword Advertising Litigation Is Waning

* Court Dumps Crappy Trademark & Keyword Ad Case–ONEPul v. BagSpot

* AdWords Buys Using Geographic Terms Support Personal Jurisdiction–Rilley v. MoneyMutual

* FTC Sues 1-800 Contacts For Restricting Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Will Go To A Jury–Edible Arrangements v. Provide Commerce

* Texas Ethics Opinion Approves Competitive Keyword Ads By Lawyers

* Court Beats Down Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit–Beast Sports v. BPI

* Another Murky Opinion on Lawyers Buying Keyword Ads on Other Lawyers’ Names–In re Naert

* Keyword Ad Lawsuit Isn’t Covered By California’s Anti-SLAPP Law

* Confusion From Competitive Keyword Advertising? Fuhgeddaboudit

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Permitted As Nominative Use–ElitePay Global v. CardPaymentOptions

* Google And Yahoo Defeat Last Remaining Lawsuit Over Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Mixed Ruling in Competitive Keyword Advertising Case–Goldline v. Regal

* Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Infogroup v. DatabaseLLC

* Damages from Competitive Keyword Advertising Are “Vanishingly Small”

* More Defendants Win Keyword Advertising Lawsuits

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails Badly

* Duplicitous Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuits–Fareportal v. LBF (& Vice-Versa)

* Trademark Owners Just Can’t Win Keyword Advertising Cases–EarthCam v. OxBlue

* Want To Know Amazon’s Confidential Settlement Terms For A Keyword Advertising Lawsuit? Merry Christmas!

* Florida Allows Competitive Keyword Advertising By Lawyers

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Unceremoniously Dismissed–Infostream v. Avid

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Allied Interstate v. Kimmel & Silverman

* More Evidence That Competitive Keyword Advertising Benefits Trademark Owners

* Suing Over Keyword Advertising Is A Bad Business Decision For Trademark Owners

* Florida Proposes to Ban Competitive Keyword Advertising by Lawyers

* More Confirmation That Google Has Won the AdWords Trademark Battles Worldwide

* Google’s Search Suggestions Don’t Violate Wisconsin Publicity Rights Law

* Amazon’s Merchandising of Its Search Results Doesn’t Violate Trademark Law

* Buying Keyword Ads on People’s Names Doesn’t Violate Their Publicity Rights

* With Its Australian Court Victory, Google Moves Closer to Legitimizing Keyword Advertising Globally

* Yet Another Ruling That Competitive Keyword Ad Lawsuits Are Stupid–Louisiana Pacific v. James Hardie

* Another Google AdWords Advertiser Defeats Trademark Infringement Lawsuit

* With Rosetta Stone Settlement, Google Gets Closer to Legitimizing Billions of AdWords Revenue

* Google Defeats Trademark Challenge to Its AdWords Service

* Newly Released Consumer Survey Indicates that Legal Concerns About Competitive Keyword Advertising Are Overblown

Pingback: Links for Week of October 25, 2024 – Cyberlaw Central()

Pingback: 2-Live Termination - Entertainment Law Update 173 - Entertainment Law Update()