Competitive Keyword Advertising Still Isn’t Trademark Infringement, Unless…. –Adler v. Reyes & Adler v. McNeil

Competitive keyword advertising lawsuits are still stupid, and they are still typically doomed in court. This is especially true in keyword advertising disputes between rival lawyers, something that I spoke out against in 2016. Despite that, one of these two companion cases survives a motion to dismiss, which might slightly encourage plaintiffs. Note that it took a combination of very specific facts and a sympathetic judge relying on very old law just to get past a motion to dismiss. YMMV.

Adler v. Reyes

[Note: Angel and I have worked together before, including co-authoring this article]

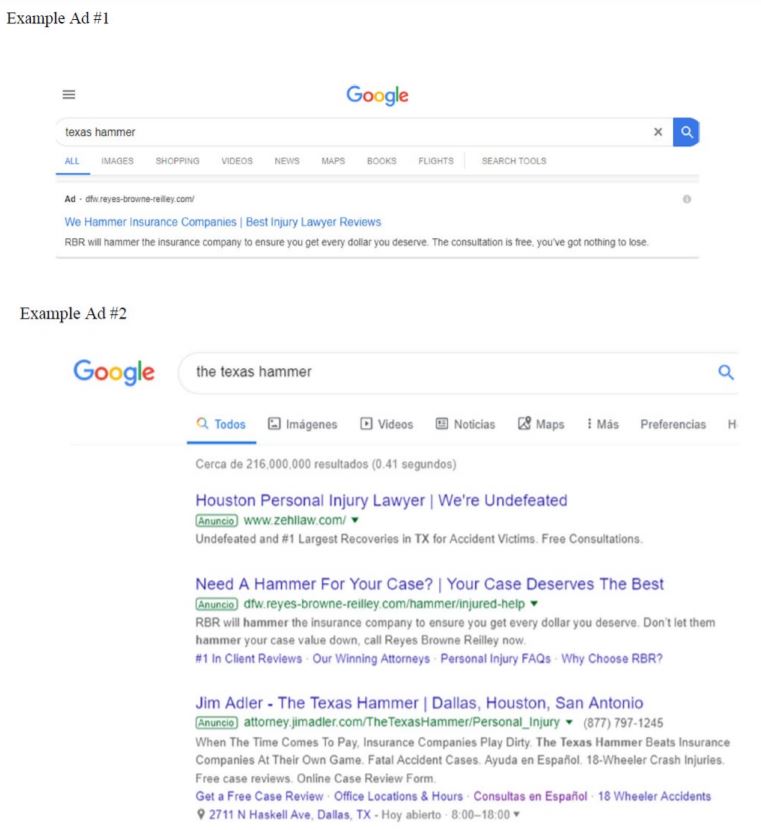

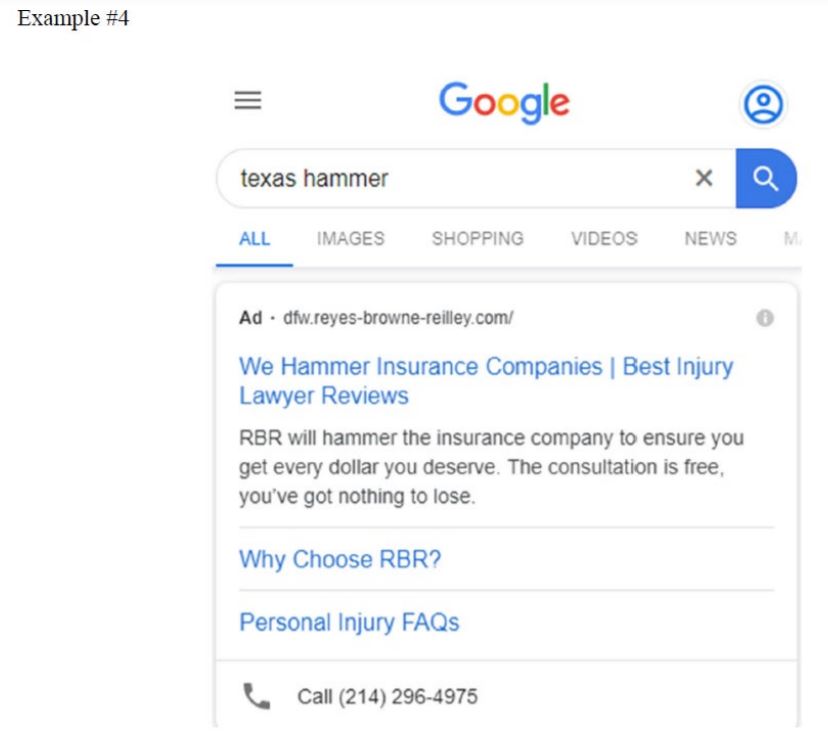

Jim Adler and Angel Reyes are rival personal injury lawyers in the Dallas metro area. “Defendant purchases the Adler Marks as keyword advertisements through Google’s search engine on mobile devices and uses them in conjunction with similar ads that incorporate Plaintiffs’ marks into the text of Defendant’s advertisement….As a result, Google searches for ‘Jim Adler,’ ‘The Texas Hammer,’ and ‘El Martillo Tejano’ result in search pages that display Defendant’s advertisements, often directly below one or more of the Adler Marks – and before Plaintiffs’ own similar ads – while often incorporating Plaintiffs’ marks into the text of Defendant’s advertisements.” For example:

The Reyes firm also did mobile advertising with click-to-call:

“Defendant’s employees are directed to answer the calls with a generic greeting like ‘did you have an accident’ or ‘tell me about your accident’ instead of identifying Defendant.”

Trademark Infringement

The court takes the competitive keyword ad purchases off the table legally. “The purchase of a competitor’s trademark as a keyword for search-engine advertising, without more, is not sufficient for a claim of trademark infringement.” However, the plaintiff alleged more than just the keyword ad buys, including:

that Defendant: (1) used confusing advertisements with Adler keywords, often incorporating the Adler marks into the text of the ads in conspicuous fonts; (2) bid increasing higher amounts so that its ads were placed near or before Plaintiffs’ ads; (3) created special landing pages incorporating the Adler marks for those who clicked on the infringing ads; (4) used click-to-call technology in the ads to cause consumers searching for Plaintiffs to mistakenly call Defendant before obtaining further information; and (5) had call-center operators follow scripts designed to further confuse callers seeking Plaintiffs in the hopes of keeping them on the phone and ultimately convincing them to hire Defendant instead of Plaintiffs

Point #1 is critical, as the companion McNeil case (discussed below) indicates. The McNeil case suggests that the court should throw out all claims predicated on ads that don’t include the plaintiff’s trademarks in the ad copy. Also, I don’t understand the significance of #2–bidding more than the trademark owner is a problem how exactly?

The court says that the plaintiff pled enough to survive the motion to dismiss. The court articulates its legal standard:

The crux of the issue is whether a defendant’s keyword purchases, combined with the look and placement of the ads, creates a search results page that misleads, confuses, or misdirects a consumer searching for a brand to the website of a competitor

What? No. This is a bastardized version of the initial interest confusion doctrine, along the lines of the now-fully-discredited 1999 Ninth Circuit Brookfield decision. Alternatively, this legal standard is a variant of bait-and-switch, but with only “bait” and no “switch” required. Even worse, this recapitulation is pointless because the court nevertheless does a standard multi-factor likelihood of consumer confusion test without further reference to the legal standard.

A few standout points in the multi-factor test:

- regarding mark similarity, the court accepts the plaintiff’s allegation that “Defendant uses terms similar to Plaintiffs’ registered trademarks and uses the identical marks as keywords to manipulate search engine results and confuse consumers, including using Alder’s marks in the ads themselves.”

- For all of the following propositions that point towards consumer confusion, the court cites to the dubious 2011 Binder v. Disability Group case, even though it probably is not considered good law in the Ninth Circuit after the Network Automation decision:

- “use of a competing law firm’s marks in keyword ads when the parties provide the same type of legal services is strong evidence of likelihood of confusion”

- “When a competing law firm uses another’s marks for keyword advertising to reach the same potential clients, there is strong evidence of likelihood of confusion”

- “When two competing law firms both use the internet to market their services and rely on it to obtain clients, this factor weighs in favor of finding the likelihood of confusion.” (I believe most circuits now discount overlaps in Internet marketing because that factor is true in every case)

All of these bullet points are in tension with the court’s earlier statement that the “purchase of a competitor’s trademark as a keyword for search-engine advertising, without more, is not sufficient for a claim of trademark infringement.” All of these points will be true in every competitive keyword advertising case, ensuring they always weigh against the defense, and none of them are predicated on the inclusion of the plaintiff’s trademark in the ad copy. So, like the pre-Network Automation caselaw, this court seems to be misapplying the standard likelihood of consumer confusion test without recognizing how poorly that test fits competitive keyword advertising. To solve this problem, the Network Automation court also noted the relevance of any labeling of the ads as ads, something this court doesn’t address.

Adler calls himself the TEXAS HAMMER, and he objected to the defendant’s use of the term “hammer” in the defendant’s ad copy statements like “we hammer insurance companies.” The defendant unsuccessfully argued the “hammer” references qualified as descriptive fair use:

Plaintiffs allege that Defendant uses the word “hammer” in a way that deceives internet consumers searching for the Adler Marks on mobile phones. In the mobile-ad context, which requires ads occupy minimal screen space and use only small amounts of screen space, they allege that Defendant’s use of the term “hammer” multiple times in a single ad deceptively directs consumers searching the Adler Marks away from Plaintiffs to Defendant

It was also irrelevant to the fair use defense that the Texas State Bar green-lighted competitive keyword ads.

I’m not sure how faithful the court’s ruling is to the KP Permanent Makeup decision, which said that descriptive fair use can apply even if there is consumer confusion. Furthermore, the companion McNeil case says that the “Lanham Act includes safeguards to prevent the commercial monopolization of language,” and I wonder if the court’s rejection of the descriptive fair use defense tends towards monopolizing the term “hammer.”

Other Claims

The state dilution claim survived because Adler alleged enough in-state fame. The tortious interference claim also survived, partially as a derivative to other claims. However, the publicity rights claim did not survive the motion to dismiss because the allegations sounded more in trademark than publicity rights.

Implications

This is an old-school opinion; the kind we used to see before the Network Automation case and rarely see now. Things like the court’s standard for what confusion counts (initial interest confusion in all but the name), and the frequent citations to Binder, are antiquated approaches. Since Network Automation, trademark infringement cases over keyword ads have largely failed, even on motions to dismiss. We’ll have to see if the plaintiff can succeed when the legal tests become more stringent.

Case citation: Jim S. Adler PC v. Angel L. Reyes & Associates PC, 2020 WL 5099596 (N.D. Tex. Aug. 7, 2020). The district court judge approved the magistrate report without comment, No. 3:19-cv-2027-K-BN (N.D. Tex. Aug. 29, 2020).

Adler v. McNeil

This is a companion case to the Reyes case, except that the defendant is a lawyer referral service rather than a competing law firm. Otherwise, this case has the same plaintiff and same magistrate judge as the Reyes case.

Phrasing the baseline law slightly differently than in the Reyes case, the magistrate says: “The purchase of a competitor’s trademark as a keyword for search-engine advertising, without more, is insufficient for a claim of trademark infringement” (cite to College Network v. Moore). Thus, “Where an advertisement does not incorporate the plaintiff’s trademark, there is no likelihood of confusion as a matter of law” (cites to 1-800 Contacts v. Lens.com, Infogroup v. Database, USA Nutraceuticals v. BPI, Tartell v. South Florida Sinus & Allergy, JG Wentworth v. Settlement Group).

That legal standard makes this an easy case:

Because Defendants do not use any portion of Plaintiffs’ marks in their ads, and Plaintiffs base their infringement claim on the use of generic terms, consideration of the “digits of confusion” is not necessary to determine that Plaintiffs fail to allege a likelihood of confusion, and, as a matter of law, fail to state a claim for violation of the Lanham Act.

In approving the magistrate opinion, the district court judge says laconically: “Plaintiffs’ claim is based solely on the purchase of Plaintiffs’ trademarks as keywords for search engine advertising and Defendants do not include Plaintiffs’ trademarks in their advertisements.”

Case citation: Jim S. Adler PC v. McNeil Consulting, LLC, 2020 WL 5134774 (N.D. Tex. Aug. 10, 2020). That is the magistrate’s report. The district court judge approved the magistrate report without change in 2020 WL 5106849 (N.D. Tex. Aug. 29, 2020).

More Posts About Keyword Advertising

* Three Keyword Advertising Decisions in a Week, and the Trademark Owners Lost Them All

* Competitor Gets Pyrrhic Victory in False Advertising Suit Over Search Ads–Harbor Breeze v. Newport Fishing

* IP/Internet/Antitrust Professor Amicus Brief in 1-800 Contacts v. FTC

* New Jersey Attorney Ethics Opinion Blesses Competitive Keyword Advertising (…or Does It?)

* Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Dr. Greenberg v. Perfect Body Image

* The Florida Bar Regulates, But Doesn’t Ban, Competitive Keyword Ads

* Rounding Up Three Recent Keyword Advertising Cases–Comphy v. Amazon & More

* Do Adjacent Organic Search Results Constitute Trademark Infringement? Of Course Not…But…–America CAN! v. CDF

* The Ongoing Saga of the Florida Bar’s Angst About Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Your Periodic Reminder That Keyword Ad Lawsuits Are Stupid–Passport Health v. Avance

* Restricting Competitive Keyword Ads Is Anti-Competitive–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* Another Failed Trademark Suit Over Competitive Keyword Advertising–JIVE v. Wine Racks America

* Negative Keywords Help Defeat Preliminary Injunction–DealDash v. ContextLogic

* The Florida Bar and Competitive Keyword Advertising: A Tragicomedy (in 3 Parts)

* Another Court Says Competitive Keyword Advertising Doesn’t Cause Confusion

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Doesn’t Show Bad Intent–ONEpul v. BagSpot

* Brief Roundup of Three Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Developments

* Interesting Tidbits From FTC’s Antitrust Win Against 1-800 Contacts’ Keyword Ad Restrictions

* 1-800 Contacts Charges Higher Prices Than Its Online Competitors, But They Are OK With That–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* FTC Explains Why It Thinks 1-800 Contacts’ Keyword Ad Settlements Were Anti-Competitive–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* Amazon Defeats Lawsuit Over Its Keyword Ad Purchases–Lasoff v. Amazon

* More Evidence Why Keyword Advertising Litigation Is Waning

* Court Dumps Crappy Trademark & Keyword Ad Case–ONEPul v. BagSpot

* AdWords Buys Using Geographic Terms Support Personal Jurisdiction–Rilley v. MoneyMutual

* FTC Sues 1-800 Contacts For Restricting Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Will Go To A Jury–Edible Arrangements v. Provide Commerce

* Texas Ethics Opinion Approves Competitive Keyword Ads By Lawyers

* Court Beats Down Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit–Beast Sports v. BPI

* Another Murky Opinion on Lawyers Buying Keyword Ads on Other Lawyers’ Names–In re Naert

* Keyword Ad Lawsuit Isn’t Covered By California’s Anti-SLAPP Law

* Confusion From Competitive Keyword Advertising? Fuhgeddaboudit

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Permitted As Nominative Use–ElitePay Global v. CardPaymentOptions

* Google And Yahoo Defeat Last Remaining Lawsuit Over Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Mixed Ruling in Competitive Keyword Advertising Case–Goldline v. Regal

* Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Infogroup v. DatabaseLLC

* Damages from Competitive Keyword Advertising Are “Vanishingly Small”

* More Defendants Win Keyword Advertising Lawsuits

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails Badly

* Duplicitous Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuits–Fareportal v. LBF (& Vice-Versa)

* Trademark Owners Just Can’t Win Keyword Advertising Cases–EarthCam v. OxBlue

* Want To Know Amazon’s Confidential Settlement Terms For A Keyword Advertising Lawsuit? Merry Christmas!

* Florida Allows Competitive Keyword Advertising By Lawyers

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Unceremoniously Dismissed–Infostream v. Avid

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Allied Interstate v. Kimmel & Silverman

* More Evidence That Competitive Keyword Advertising Benefits Trademark Owners

* Suing Over Keyword Advertising Is A Bad Business Decision For Trademark Owners

* Florida Proposes to Ban Competitive Keyword Advertising by Lawyers

* More Confirmation That Google Has Won the AdWords Trademark Battles Worldwide

* Google’s Search Suggestions Don’t Violate Wisconsin Publicity Rights Law

* Amazon’s Merchandising of Its Search Results Doesn’t Violate Trademark Law

* Buying Keyword Ads on People’s Names Doesn’t Violate Their Publicity Rights

* With Its Australian Court Victory, Google Moves Closer to Legitimizing Keyword Advertising Globally

* Yet Another Ruling That Competitive Keyword Ad Lawsuits Are Stupid–Louisiana Pacific v. James Hardie

* Another Google AdWords Advertiser Defeats Trademark Infringement Lawsuit

* With Rosetta Stone Settlement, Google Gets Closer to Legitimizing Billions of AdWords Revenue

* Google Defeats Trademark Challenge to Its AdWords Service

* Newly Released Consumer Survey Indicates that Legal Concerns About Competitive Keyword Advertising Are Overblown

Pingback: News of the Week; September 9, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall()