Three Keyword Advertising Decisions in a Week, and the Trademark Owners Lost Them All

If you are a trademark owner suing over competitive keyword ads, you are almost certainly making a bad business decision, and your attorney might be milking your bank account. If you are an attorney representing a trademark owner in a competitive keyword ad lawsuit, please reexamine your professional decision-making to ensure that you are, in fact, prioritizing the best interests of your clients.

If you are a trademark owner suing over competitive keyword ads, you are almost certainly making a bad business decision, and your attorney might be milking your bank account. If you are an attorney representing a trademark owner in a competitive keyword ad lawsuit, please reexamine your professional decision-making to ensure that you are, in fact, prioritizing the best interests of your clients.

This is my first time blogging keyword ad cases in almost a year. However, in an odd coincidence, we got three rulings in the same week. When it rains, it pours. This post rounds up how trademark owners are doing in these cases (TL;DR: they lose). I don’t have a conclusion at the end of this post because, honestly, what’s left to say? If the conclusion to this post isn’t obvious after reading it, take off your plaintiff-colored glasses.

Passport Health, LLC v. Avance Health System, Inc., 2020 WL 4700887 (4th Cir. Aug. 13, 2020). Prior blog post.

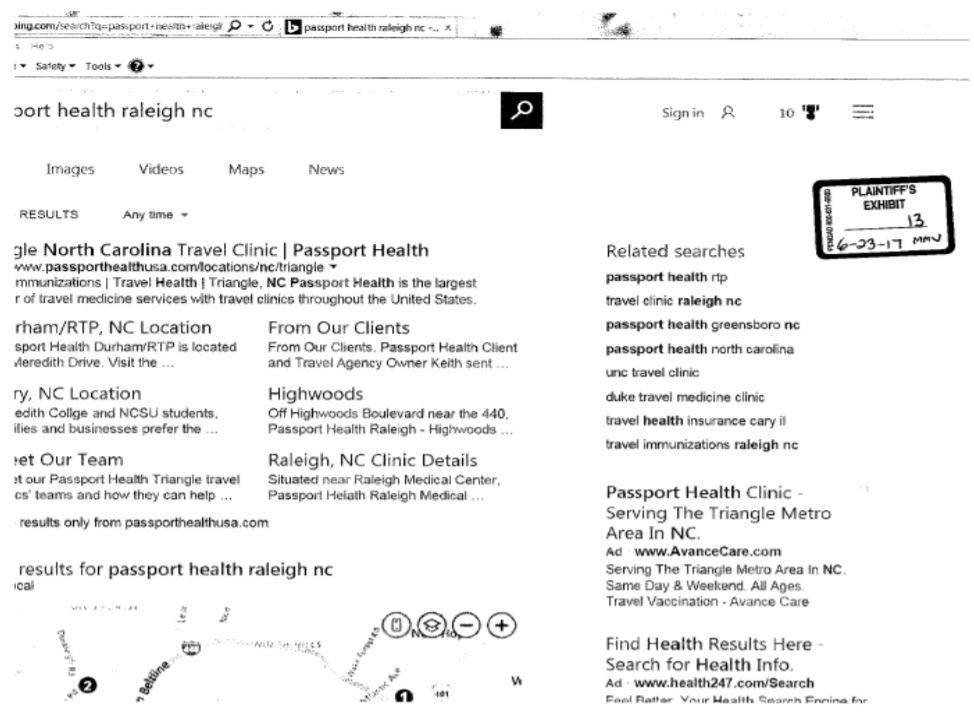

Avance bid on the term “Passport Health” at Google and Bing from 2011 to 2013. It ignored a C&D letter but, when sued, wrote a letter saying it had stopped the ads and wouldn’t resume. Avance then switched SEM firms, but for unexplained reasons, the new firm bid on “Passport Health” in Bing until 2017:

I know what you’re thinking: who gives a 🐀🍑 about Bing keyword ads??? Your skepticism is justified in this case:

Data from Bing shows that from 2014 to 2017 (when the campaign was in fact stopped), the advertisement resulting from the campaign generated forty-one clicks, seven of which occurred in the same month this suit was filed.

So here we are, in the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, fighting over the legal consequences of 41 clicks, generated at the rate of about 1 click per month. I’m not sure what emotional reaction to include. Uncontrollable sobbing? Maniacal laughing and finger pointing at the plaintiff? Disgust that this lawsuit has consumed judicial resources for years? Help me out here.

The court says that the trademark owner didn’t develop its arguments over competitive keyword advertising that doesn’t include the trademark in the ad copy. So the only question on the table is whether the ads including the trademark in the ad copy infringe.

The appeals court runs through a streamlined multi-factor LOCC test. Some highlights:

Mark similarity. Following the Lamparello approach for domain names, the court says that comparing mark similarity requires consideration of both the mark and the linked website: “the proper context here includes Avance’s website…Passport focuses on whether the use of its marks will lure consumers to its competitor’s website, regardless of whether the content of the website will dispel the consumers’ confusion. Thus, though Passport never references the initial interest confusion doctrine, its argument relies on it. As in Lamparello, we decline to adopt the doctrine here.”

My obligatory reminder that the only thing stupider than competitive keyword advertising lawsuits are IIC lawsuits. This appears to be about as emphatic as the court will express that IIC doesn’t exist in the Fourth Circuit. This does require the court to do some fancy footwork to distinguish the Rosetta Stone v. Google precedent.

Regarding the combination of the ads with the promoted pages, “any confusion from Avance’s use of Passport’s marks in its advertisement is dispelled when consumers reach the website.” The court explains:

The website’s domain name is “www.avancecare.com,” it features the “Avance Care” mark at the top of every page, and it doesn’t mention “passport health.” The home page also doesn’t mention travel health services, and once a consumer reaches the travel health services page, it too bears the “Avance Care” mark and doesn’t mention “passport health.” No reasonable juror could conclude that consumers would be confused as to whether Passport provides the services described on the website or is affiliated with them.

Intent. Because Avance stopped the keyword ads in 2013 and told its SEM to stop, and no one can explain why the new SEM continued with Bing, the trademark owner didn’t adequately show bad intent.

Actual Confusion. “No reasonable juror could find a likelihood of confusion where there were six years of overlapping use and there’s no evidence of actual confusion. And even assuming that all forty-one clicks on the advertisement were by confused consumers, that confusion is de minimis.” THIS IS A WARNING TO LITIGIOUS TRADEMARK OWNERS, AND THEIR ENABLING LAWYERS, WHO THINK THAT A FEDERAL APPEAL OVER 41 BING CLICKS IS A WISE DECISION: “DE MINIMIS CONFUSION.”

Thus, the court says not enough factors indicate LOCC.

In my prior post, I wondered if Avance might get a fee shift under federal trademark law as an extraordinary case. The tenor of this appellate decision makes me think not; despite the obvious bases to do so, the court didn’t mock the trademark owner. Still, if I were Avance, I’d ask for it. The appellate opinion repeatedly says that “no reasonable juror” could agree with the case, and the court says it’s all de minimis confusion in the end. This case never should have been brought, and definitely should not have been appealed. WHAT A WASTE.

This opinion partially corrects the Fourth Circuit’s lousy Rosetta Stone opinion from 2012. However, because this opinion isn’t precedential, the Rosetta Stone precedent lives on. I think attitudes towards keyword advertising have changed so much since 2012 that Rosetta Stone doesn’t predict how future keyword ad cases will go. I think this ruling is a better predictor.

Smash Franchise Partners LLC v. Kanda Holdings Inc., 2020 WL 4692287 (Del. Ct. Chancery Aug. 13, 2020)

This is an unusual venue for a trademark dispute over keyword ads. On the plus side, it’s nice to get a fresh perspective on the issue.

This case involves the “mobile trash compaction” industry. Yes, this case is literally trash. The defendant is “Dumpster Devil.” Much of this case involves a failed franchise acquisition that prompted the defendant to create a competitive franchise offering.

I’ll focus on Dumpster Devil’s purchase of competitive keyword ads. The court’s entire analysis:

Proving actual confusion is a “very fact intensive” undertaking. The burden is significantly heavier if the buyers have expertise in the field or the goods are relatively expensive.

A claim of confusion based on paid website advertisements will not succeed if the search engine “partitioned their search results pages so that the advertisements appear in separately labeled sections for sponsored links” and “the labeling and appearance of the advertisements as they appear on the results page includes more than the text of the advertisement.” [cite to Network Automation]

Smash has grounded its claim of confusion on an AdWords campaign where Dumpster Devil’s product appeared as a paid advertisement. Although Smash does not necessarily market to experts in the field, it sells an expensive product to individuals who are likely to conduct research before making a purchase. According to Smash’s Disclosure Documents, it costs between $220,000 and $240,000 to start a Smash franchise. Smash and Dumpster Devil market their products to individuals who are interested in starting a business. A prospective purchase is likely to perform due diligence before making this type of investment.

Given these facts, the likelihood of actual confusion is quite low. Smash’s only evidence consists of a picture of Google’s current landing page for Dumpster Devil’s advertisement. The advertisement states, “Compare Our Dumpster Smasher–No Franchise Fees, Higher ROI.” Google marks Dumpster Devil’s listing with the bolded word “Ad” on the upper right-hand corner. The advertisement does not display Smash’s mark.

Under established precedent, this quantum of evidence is not sufficient to support a claim of actual confusion. Smash has failed to establish a reasonable likelihood of success on its trademark infringement claim.

As it turned out, the only thing that got smashed here is the trademark owner’s claim. The court put that claim in the dumpster where it belongs.

Sen v. Amazon.com, Inc., 2020 WL 4582678 (S.D. Cal. Aug. 10, 2020). Prior blog post; and also referenced here.

This is a long-running litigation campaign over the “Baiden Mitten” trademark. The trademark owner doesn’t like that Amazon purchases search engine keyword ads on the term to bring customers into Amazon’s virtual premises, where rival goods may be promoted. This bears some commonalities with the Multi-Time Machine litigation, though that dealt with search results from Amazon’s internal search, not from Amazon’s ads placed at third-party search engines.

In 2013, the parties settled the lawsuit in a messy way–via a binding MOU that contemplated the preparation of a more formal settlement agreement they never agreed upon. The court upheld the binding MOU. The trademark owner claimed the MOU only covered past infringements, not future ones. The court says the MOU signals the parties’ intent to waive all claims, including future ones. So the release in the settlement applies here.

Further, the court says the trademark owner loses even if MOU doesn’t apply. The court applies the modified 4-factor LOCC test from Network Automation:

Mark strength. The court says “Baiden Mitten” is suggestive (of what, though?), others are using the mark in commerce, and the trademark owner didn’t show commercial strength of the mark.

Actual confusion. The trademark owner pointed to a single email that allegedly showed a confused customer, but the court says the email wasn’t clear who was confused about what. Thus, the court calls this single email “de minimis evidence.”

Purchaser care. “Although Plaintiff’s products appear to be inexpensive, Amazon’s online marketplace shows that they can be viewed as above market standard when compared alongside a competitor’s similar products.” You can buy an exfoliating rag for $5, while the trademark owner’s mittens cost $48. “[C]onsumers are likely to be more aware when purchasing products of higher value and price. Additionally, a reasonably prudent consumer is likely to exercise a high degree of care when purchasing facial and body products. Specifically, to avoid a potential outbreak or allergic reaction.”

Ad labeling. Everyone seems to agree that the ad labeling is clear, and “even if potential consumers were to click on Amazon’s keyword advertisement, this would be intentional and not due to confusion as the sponsored advertisements are clearly distinguishable from the objective search results.”

An easy win for Amazon in courtroom tussles that have been on-going for 8 years and probably will make a trip to the Ninth Circuit again.

More Posts About Keyword Advertising:

* Competitor Gets Pyrrhic Victory in False Advertising Suit Over Search Ads–Harbor Breeze v. Newport Fishing

* IP/Internet/Antitrust Professor Amicus Brief in 1-800 Contacts v. FTC

* New Jersey Attorney Ethics Opinion Blesses Competitive Keyword Advertising (…or Does It?)

* Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Dr. Greenberg v. Perfect Body Image

* The Florida Bar Regulates, But Doesn’t Ban, Competitive Keyword Ads

* Rounding Up Three Recent Keyword Advertising Cases–Comphy v. Amazon & More

* Do Adjacent Organic Search Results Constitute Trademark Infringement? Of Course Not…But…–America CAN! v. CDF

* The Ongoing Saga of the Florida Bar’s Angst About Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Your Periodic Reminder That Keyword Ad Lawsuits Are Stupid–Passport Health v. Avance

* Restricting Competitive Keyword Ads Is Anti-Competitive–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* Another Failed Trademark Suit Over Competitive Keyword Advertising–JIVE v. Wine Racks America

* Negative Keywords Help Defeat Preliminary Injunction–DealDash v. ContextLogic

* The Florida Bar and Competitive Keyword Advertising: A Tragicomedy (in 3 Parts)

* Another Court Says Competitive Keyword Advertising Doesn’t Cause Confusion

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Doesn’t Show Bad Intent–ONEpul v. BagSpot

* Brief Roundup of Three Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Developments

* Interesting Tidbits From FTC’s Antitrust Win Against 1-800 Contacts’ Keyword Ad Restrictions

* 1-800 Contacts Charges Higher Prices Than Its Online Competitors, But They Are OK With That–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* FTC Explains Why It Thinks 1-800 Contacts’ Keyword Ad Settlements Were Anti-Competitive–FTC v. 1-800 Contacts

* Amazon Defeats Lawsuit Over Its Keyword Ad Purchases–Lasoff v. Amazon

* More Evidence Why Keyword Advertising Litigation Is Waning

* Court Dumps Crappy Trademark & Keyword Ad Case–ONEPul v. BagSpot

* AdWords Buys Using Geographic Terms Support Personal Jurisdiction–Rilley v. MoneyMutual

* FTC Sues 1-800 Contacts For Restricting Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Will Go To A Jury–Edible Arrangements v. Provide Commerce

* Texas Ethics Opinion Approves Competitive Keyword Ads By Lawyers

* Court Beats Down Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit–Beast Sports v. BPI

* Another Murky Opinion on Lawyers Buying Keyword Ads on Other Lawyers’ Names–In re Naert

* Keyword Ad Lawsuit Isn’t Covered By California’s Anti-SLAPP Law

* Confusion From Competitive Keyword Advertising? Fuhgeddaboudit

* Competitive Keyword Advertising Permitted As Nominative Use–ElitePay Global v. CardPaymentOptions

* Google And Yahoo Defeat Last Remaining Lawsuit Over Competitive Keyword Advertising

* Mixed Ruling in Competitive Keyword Advertising Case–Goldline v. Regal

* Another Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Infogroup v. DatabaseLLC

* Damages from Competitive Keyword Advertising Are “Vanishingly Small”

* More Defendants Win Keyword Advertising Lawsuits

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails Badly

* Duplicitous Competitive Keyword Advertising Lawsuits–Fareportal v. LBF (& Vice-Versa)

* Trademark Owners Just Can’t Win Keyword Advertising Cases–EarthCam v. OxBlue

* Want To Know Amazon’s Confidential Settlement Terms For A Keyword Advertising Lawsuit? Merry Christmas!

* Florida Allows Competitive Keyword Advertising By Lawyers

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Unceremoniously Dismissed–Infostream v. Avid

* Another Keyword Advertising Lawsuit Fails–Allied Interstate v. Kimmel & Silverman

* More Evidence That Competitive Keyword Advertising Benefits Trademark Owners

* Suing Over Keyword Advertising Is A Bad Business Decision For Trademark Owners

* Florida Proposes to Ban Competitive Keyword Advertising by Lawyers

* More Confirmation That Google Has Won the AdWords Trademark Battles Worldwide

* Google’s Search Suggestions Don’t Violate Wisconsin Publicity Rights Law

* Amazon’s Merchandising of Its Search Results Doesn’t Violate Trademark Law

* Buying Keyword Ads on People’s Names Doesn’t Violate Their Publicity Rights

* With Its Australian Court Victory, Google Moves Closer to Legitimizing Keyword Advertising Globally

* Yet Another Ruling That Competitive Keyword Ad Lawsuits Are Stupid–Louisiana Pacific v. James Hardie

* Another Google AdWords Advertiser Defeats Trademark Infringement Lawsuit

* With Rosetta Stone Settlement, Google Gets Closer to Legitimizing Billions of AdWords Revenue

* Google Defeats Trademark Challenge to Its AdWords Service

* Newly Released Consumer Survey Indicates that Legal Concerns About Competitive Keyword Advertising Are Overblown

Pingback: News of the Week; August 19, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall()