Uber’s Contract Upheld in Second Circuit–Meyer v. Uber

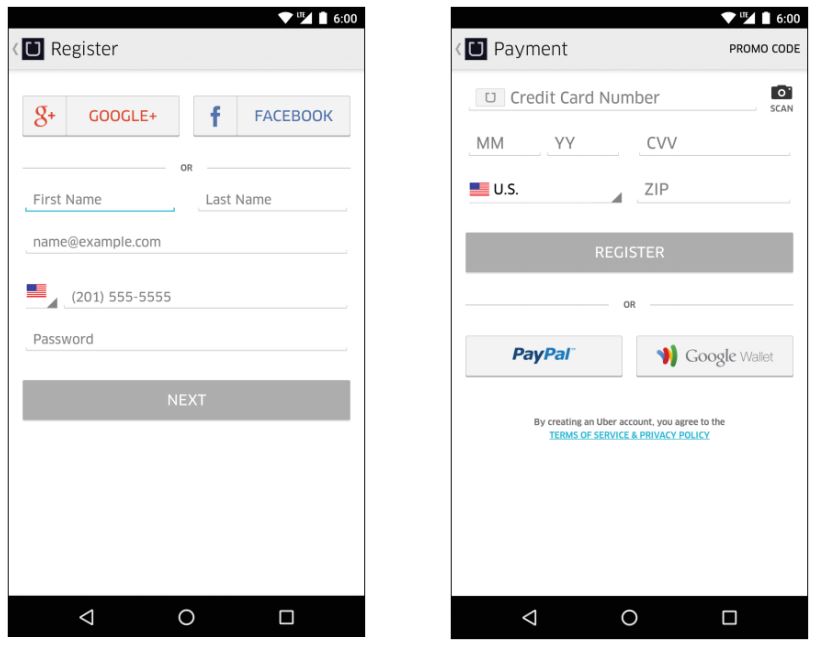

This is a lawsuit alleging price fixing against Uber and its former CEO Travis Kalanick. Uber (and Kalanick) moved to compel arbitration on the basis of the arbitration clause in Uber’s terms of service. The district court found that Uber’s sign-up process failed to effectively form an agreement, so it declined to send the case to arbitration. (My blog post on the trial court ruling here: “Judge Declines to Enforce Uber’s Terms of Service–Meyer v. Kalanick“). The Second Circuit reverses and orders arbitration. Here are the relevant screenshots, helpfully included in the opinion:

Uber does not force its users to check the box during the sign up process indicating users’ assent to the terms. The court is thus forced to evaluate whether the plaintiff (Meyer) is on actual or inquiry notice, and whether he indicated assent.

The court takes a tour through the familiar landscape of online agreements, ranging from “browsewraps” to “sign-in wraps” to “scrollwraps.” This particular agreement does not appear to fit neatly into any of those categories, in that at the time of sign-up, the user is presented with hyperlinks to bold text that states:

By creating an Uber account, you agree to the TERMS OF SERVICE & PRIVACY POLICY.

The key question is whether Uber’s presentation of this text and (link) was reasonably conspicuous. The court says yes. Looking at the question from the perspective of a “reasonably prudent smartphone” user, and taking into the account the ubiquity of apps, the court presumes some familiarity with the phone-based contracting process:

a reasonably prudent smartphone user knows that text that is highlighted in blue and underlined is hyperlinked to another webpage where additional information will be found.

The court further says that the sign-in (payment screen) is “uncluttered,” the user does not need to scroll to see the hyperlinked terms, and the terms are in dark print which contrasts with the bright white background. The court contrasts the placement of the hyperlinked terms with those of Nicosia, where the court said that it was debatable whether an Amazon user was on inquiry notice of the terms.

The court also distinguishes another case, Schnabel, where the court declined to enforce online terms (in that instance emailed after the fact). The court says that the notice is “temporally coupled” with the registration process.

Citing Fteja, the court says the availability of the terms by hyperlink doesn’t change the analysis:

As long as the hyperlinked text was itself reasonably conspicuous ‐‐ and we conclude that it was ‐‐ a reasonably prudent smartphone user would have constructive notice of the terms. While it may be the case that many users will not bother reading the additional terms, that is the choice the user makes

Finally, the court says that the manifestation of assent is sufficient. The fact that clicking the register button has two functions does not undermine Meyer’s assent.

__

Courts’ treatment of the online contracting process is a mess, as an August round up post from last year noted. This case, and the conflicting conclusions between the district court and the appeals court, is a good illustration of the unpredictable outcomes. Courts make a lot of assumptions in employing the reasonably prudent consumer (or in this case smartphone user) test, so the outcome is truly judge-dependent.

There is an easy solution: courts should force companies to set up contracting processes that leave little room for doubt. Perhaps courts take the perspective that it’s all academic anyway. Even if Uber had required a consumer to check the box, this is no guarantee that a customer read and agreed to the terms. Perhaps courts are simply dispensing with the legal fiction of user assent to online terms?

Bonus EDNY track: Starke v. SquareTrade involved terms that were not presented to the user at the time of purchase. SquareTrade sells protection plans for consumer products. It emails the protection plan contracts after the purchase occurs. The court says post-sale confirmation emails sent by SquareTrade did not make the applicable terms “readily and obviously available.” The terms were not contained in the body of the email, and the link was buried. The court cites to a test from Berkson v. Gogo and says it has been cited favorably by federal and state trial courts. We have blogged a few cases where it’s not readily feasible for a company to present and obtain agreement to terms at the time of payment. There is not an easy solution in practice. Perhaps SquareTrade should have made the contract itself downloadable and forced the user to click that he or she agreed to it? SquareTrade had an opportunity to require the customer to check the box when the customer is asked to submit the underlying receipt which SquareTrade offers to track, but it failed to do so.

__

Eric’s Comments:

* I agree 100% with Venkat that the state of online contract formation law is a mess. Mostly I blame the proliferation of “wrap” nomenclature, with definitions that overlap and thus guarantee judicial confusion. The proliferation of “wrap” terminology has also effectively raised the bar for online contract formation. Not that long ago, it was 100% clear that a “clickthrough” agreement included a user interface where the “register” button (or whatever it was called) simultaneously communicated the user’s desire to proceed and agreement with terms that had been linked. Now, because of misconstruction of the “clickwrap” and “browsewrap” terms (and don’t get me started on BS like “scrollwrap” and “sign-in-wrap”), an online contract formation probably requires an extra checkbox and user click to assent to the terms, just to avoid courts reaching unexpected and even stupid results. As Venkat suggests, maybe this is a net win for our community, as companies adopt more “judge-proof” implementations that leave no room for doubt. Still, we should not have had to go this far, yet here we are.

* Another possible explanation for the doctrinal mess is the Second Circuit, which has swung between some strongly pro-contract-formation rulings like the Register.com v. Verio ruling and perhaps this one; and a number of strongly anti-contract formation rulings, such as the Sgouros or Nicosia cases. While it might be possible to draw a coherent line to show how all of the Second Circuit online contract formation cases cohere, it might be easier to show that the results aren’t really consistent with each other and the circuit is careening between formation jurisprudential extremes from panel to panel.

* Once again, the court reverts to standard principles of contract formation law rather than relying on categorizing the “wrap” flavor. That’s the good news. The bad news is that the court, in what is seemingly dicta, goes ahead and adopts definitions for the various “wrap” flavors, including the “scrollwrap” and “sign-in-wrap” terms first offered in the Berkson case. Oh great. So will future Second Circuit courts similarly revert to default formation principles, or will they cite the dicta definitions? We all know how that will turn out.

So here are the newly polished Second Circuit definitions:

– clickwrap/clickthrough agreements “require users to click an ‘I agree’ box after being presented with a list of terms and conditions of use.” Recall my assertion above that this definition has tightened up substantially over the years.

– “browsewraps” (a term I still believe you should never use except with derision) “generally post terms and conditions on a website via a hyperlink at the bottom of the screen”

– “scrollwraps” (Never use this term. NEVER) “require the user to scroll through the terms before the user can indicate his or her assent by clicking ‘I agree.'” This used to be a clickthrough agreement.

– “sign-in-wraps” (another term you should NEVER use) “notify the user of the existence of the websiteʹs terms of use and, instead of providing an ‘I agree’ button, advise the user that he or she is agreeing to the terms of service when registering or signing up.” This also used to be a clickthrough agreement.

Where did Uber’s presentation fit in this spectrum? The court doesn’t say! After some exposition of the definitions, the court says: “Classification of web‐based contracts alone, however, does not resolve the notice inquiry.” Great–I agree! But why then did the court discuss the classification system at all, especially if the court didn’t use any of the definitions to resolve where to place Uber’s presentation???

* As for default contract formation law, this case generates this legal standard:

Where there is no evidence that the offeree had actual notice of the terms of the agreement, the offeree will still be bound by the agreement if a reasonably prudent user would be on inquiry notice of the terms….only if the undisputed facts establish that there is ʺ[r]easonably conspicuous notice of the existence of contract terms and unambiguous manifestation of assent to those termsʺ will we find that a contract has been formed…

Insofar as it turns on the reasonableness of notice, the enforceability of a web‐ based agreement is clearly a fact‐intensive inquiry. Nonetheless, on a motion to compel arbitration, we may determine that an agreement to arbitrate exists where the notice of the arbitration provision was

reasonably conspicuous and manifestation of assent unambiguous as a matter of law.

The court doesn’t clearly explain why the plaintiff didn’t have actual notice of the terms. The court says “Meyer attests that he was not on actual notice of the hyperlink to the Terms of Service or the arbitration provision itself, and defendants do not point to evidence from which a jury could infer otherwise.” But plaintiffs will routinely deny getting actual notice, and the court doesn’t tell us what other persuasive evidence Uber could have adduced. As Venkat suggests, would a checkbox just for acknowledgement and acceptance of the terms have placed Uber in the “actual notice” category? Who knows.

The court turns to the reasonableness of Uber’s notice. First, it articulates the “reasonably prudent smartphone user” standard:

when considering the perspective of a reasonable smartphone user, we need not presume that the user has never before encountered an app or entered into a contract using a smartphone. Moreover, a reasonably prudent smartphone user knows that text that is highlighted in blue and underlined is hyperlinked to another webpage where additional information will be found

The court doesn’t say so expressly, but this ruling pretty clearly seems to overturn the June 2017 SDNY Applebaum v. Lyft ruling, where the court had said: “A reasonable consumer would not have understood that the light blue “Terms of Service” hyperlinked to a contract for review. Lyft argues that coloring words signals “hyperlink” to the reasonable consumer, but the tech company assumes too much. Coloring can be for aesthetic purposes. Courts have required more than mere coloring to indicate the existence of a hyperlink to a contract…. Beyond the coloring, there were no familiar indicia to inform consumers that there was in fact a hyperlink that should be clicked and that a contract should be reviewed, such as words to that effect, underlining, bolding, capitalization, italicization, or large font.” That sounds like it’s no longer good law in the Second Circuit.

As a result, the court expressly endorses Uber’s approach:

The Payment Screen is uncluttered, with only fields for the user to enter his or her credit card details, buttons to register for a user account or to connect the userʹs pre‐existing PayPal account or Google Wallet to the Uber account, and the warning that ʺBy creating an Uber account, you agree to the TERMS OF SERVICE & PRIVACY POLICY.ʺ The text, including the hyperlinks to the Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, appears directly below the buttons for registration. The entire screen is visible at once, and the user does not need to scroll beyond what is immediately visible to find notice of the Terms of Service. Although the sentence is in a small font, the dark print contrasts with the bright white background, and the hyperlinks are in blue and underlined.

[plus the “temporal coupling” Venkat mentions:] notice of the Terms of Service is provided simultaneously to enrollment, thereby connecting the contractual terms to the services to which they apply. We think that a reasonably prudent smartphone user would understand that the terms were connected to the creation of a user account.

The court concludes: ” A reasonable user would know that by clicking the registration button, he was agreeing to the terms and conditions accessible via the hyperlink, whether he clicked on the hyperlink or not.” Contract formed!

* So what implications does this ruling have for Uber’s other contract formation cases involving mandatory arbitration? This opinion is a powerful endorsement of Uber’s practices, so it seems to position Uber well to roll up the caselaw in other jurisdictions, at least those cases predicated on the same user interface interpreted here. Furthermore, Lyft’s contract formation process got an indirect boost as well, so expect it to enthusiastically cite this ruling too.

Case citation: Meyer v. Uber Technologies, Inc., 2017 WL 3526682 (2d Cir. Aug. 17, 2017)

Related posts:

Judge Declines to Enforce Uber’s Terms of Service–Meyer v. Kalanick

Anarchy Has Ensued In Courts’ Handling of Online Contract Formation (Round Up Post)

Evidentiary Failings Undermine Arbitration Clauses in Online Terms

Court Enforces Arbitration Clause in Amazon’s Terms of Service–Fagerstrom v. Amazon

‘Flash Sale’ Website Defeats Class Action Claim With Mandatory Arbitration Clause–Starke v. Gilt

Some Thoughts On General Mills’ Move To Mandate Arbitration And Waive Class Actions

Qwest Gets Mixed Rulings on Contract Arbitration Issue—Grosvenor v. Qwest & Vernon v. Qwest

Zynga Wins Arbitration Ruling on “Special Offer” Class Claims Based on Concepcion — Swift v. Zynga

“Modified Clickwrap” Upheld In Court–Moule v. UPS

Defective Call-to-Action Dooms Online Contract Formation–Sgouros v. TransUnion

Court Rejects “Browsewrap.” Is That Surprising?–Long v. ProFlowers

Telephony Provider Didn’t Properly Form a “Telephone-Wrap” Contract–James v. Global Tel*Link

2H 2015 Quick Links, Part 7 (Marketing, Advertising, E-Commerce)

Second Circuit Enforces Terms Hyperlinked In Confirmation Email–Starkey v. G Adventures

If You’re Going To Incorporate Online T&Cs Into a Printed Contract, Do It Right–Holdbrook v. PCS

Clickthrough Agreement Upheld–Whitt v. Prosper

The “Browsewrap”/”Clickwrap” Distinction Is Falling Apart

Safeway Can’t Unilaterally Modify Online Terms Without Notice

Clickthrough Agreement With Acknowledgement Checkbox Enforced–Scherillo v. Dun & Bradstreet

How To Get Your Clickthrough Agreement Enforced In Court–Moretti v. Hertz