Clickthrough Agreement Upheld–Whitt v. Prosper

I’m way behind in blogging clickthrough agreement cases, but I’m prioritizing this opinion because of its simplicity. Whitt, who is deaf, sought a loan via a “peer-to-peer lending service” called Prosper. To confirm his identity, Whitt needed to make a phone call. He tried to use a Video Relay Service, but Prosper allegedly refused a call made that way. Whitt claims the refusal violated the Americans With Disabilities Act and related state laws.

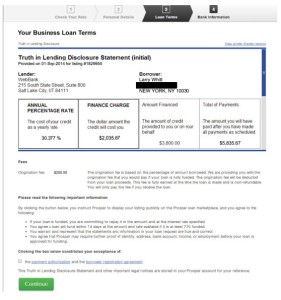

To apply for the loan, Whitt allegedly had to agree to Prosper’s Borrower Registration Agreement, which required applicants to click a box adjacent to the bolded text “Clicking the box below constitutes your acceptance of … the borrower registration agreement.” Here is the screenshot Prosper submitted:

The borrower registration agreement contained an arbitration clause that users could opt-out of by sending notice within 30 days of contract formation. Whitt didn’t opt out, so Prosper moved to send this to arbitration. The court upholds the contract formation even though the agreement terms were visible only if Whitt clicked on the hyperlink:

Whitt thereby indicated that he had at least constructive knowledge of the terms of the Agreement and that he assented to those terms. Thus, Prosper has demonstrated that Whitt accepted the terms of the Agreement, including its arbitration provision, when he applied for a loan.

In his opposition papers, Whitt suggests that he was not even constructively aware of the terms of the Agreement because those terms were viewable only by following a hyperlink. Whitt, however, does not contend that the hyperlink at issue was insufficiently conspicuous, and cites no authority indicating that a reasonably prudent website user lacks sufficient notice of terms of an agreement that are viewable through a conspicuous hyperlink. Moreover, Whitt simply ignores an abundance of persuasive authority—with which this Court agrees—supporting a proposition to the contrary.

The court’s cites include Fteja v. Facebook, Zaltz v. JDate, Nicosia v. Amazon, Starke v. Gilt and others.

Photo credit: Woman wrapped in bubble wrap // ShutterStock

Whitt also complained that he lost the ability to review the agreement terms when Prosper suspended his account 4 days later. The court calls that argument “frivolous.” As I blogged in the JDate case, “Courts Won’t Bail You Out If You Can’t Remember What Contract Terms You’ve Agreed To.” At one point, Denise Howell suggested that we need an app or plug-in that automatically collects and stores copies of online contracts as we enter into them. That still sounds a good idea to me.

Whitt also provided evidence that he was “impoverished” and therefore sending the case to arbitration was unconscionable. Prosper’s agreement specified that Prosper would cover some arbitration costs, and the selected arbitration provider (JAMS) had an arbitration rule reducing the costs borne by a consumer in a low-scale consumer arbitration. Collectively, these are enough to convince the court that the arbitration clause wasn’t unreasonable. This case supports the proposition that online vendors should voluntarily bear some extra costs of the arbitration to reduce the risk of an unconscionability challenge to the arbitration clause.

Case citation: Whitt v. Prosper Funding LLC, 2015 WL 4254062 (S.D.N.Y. July 14, 2015)