A 512(f) Plaintiff Wins at Trial! 👀–Alper Automotive v. Day to Day Imports

Background

A refresher: in 1998, Congress created a notice-and-takedown scheme for user-submitted items that allegedly infringe copyright. Copyright owners send takedown notices, and service providers either remove the items or lose the safe harbor. Congress recognized how much power it was giving copyright owners in this scheme, so it tried to curb takedown notice abuse in a few ways. For example, it defined what qualified as a 512(c)(3) takedown notice and required submitters to declare under penalty of perjury that they were acting on the copyright owner’s behalf. I’m not aware of any associated perjury prosecutions in the last 23 years, even though I’m sure prosecutors could find violations if they looked hard enough.

The DMCA’s main counterbalance to copyright owner overreach was supposed to be 512(f). 512(f) is a cause of action for abusive takedown notices. In theory, 512(f) makes copyright owners do their homework and think carefully before they weaponize a copyright takedown notice.

As I’ve blogged many, many times on this blog (see list below), 512(f) has been a complete failure. In 2004, the Ninth Circuit eviscerated it (in the Rossi case) by requiring plaintiffs to show that senders subjectively believed their takedown notices were abusive. Plaintiffs can’t show this because they don’t have the evidence of subjective belief when they file their complaints. As a double-insult, 512(f) preempts related state law claims over abusive takedown notices, so it actually leaves victims worse off than if 512(f) didn’t exist by clearing out the field.

As a result, we’ve seen very, very few successful 512(f) enforcements. The Lenz case got a lot of press, but it ended with a confidential settlement. A few plaintiffs have won default judgments (including one I blog below). To my knowledge, the only litigated case that resulted in a 512(f) win was Online Policy Group v. Diebold from 2004, which led to a $125k damages award.

A New 512(f) Plaintiff Win!

To this paltry record of plaintiff success, we can now add this case. After a 3 day bench trial, the court ruled for the 512(f) plaintiff. But even this win reiterates how 512(f) is mostly useless.

The Proxy War at Amazon

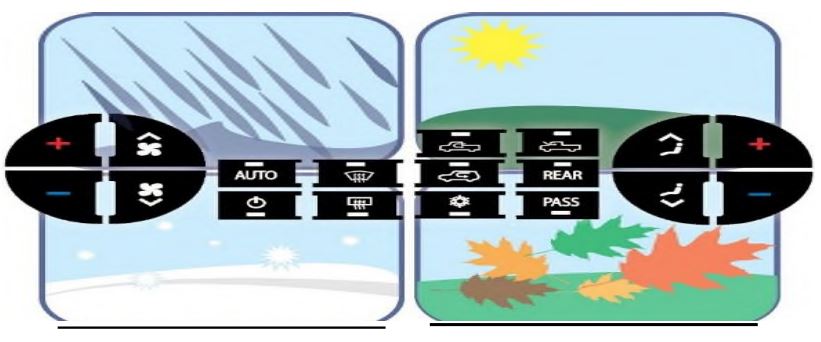

The facts are pretty confusing. The precedent work is “a set of replacement stickers for the dashboard climate controls for certain GM vehicles”:

The Copyright Office registered this design.

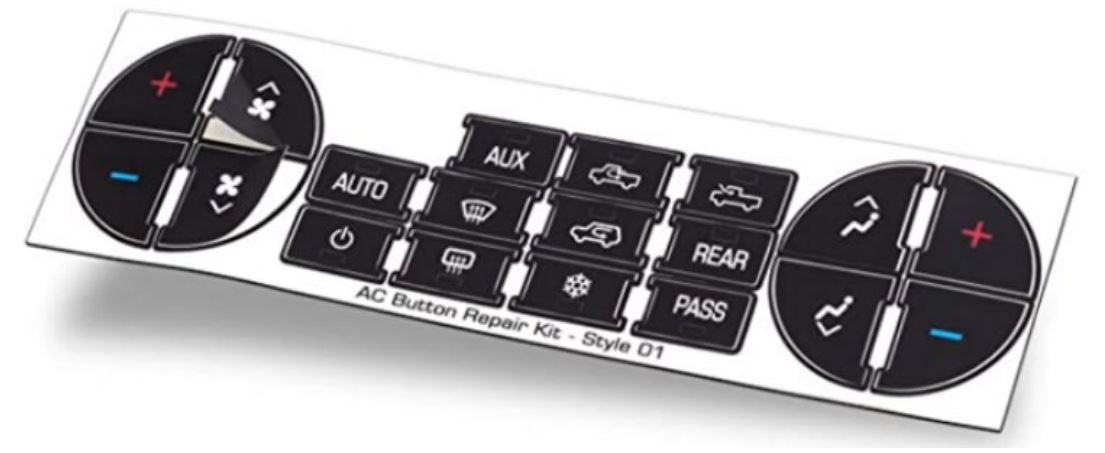

This is the initial copying design (without the background graphics in the precedent work):

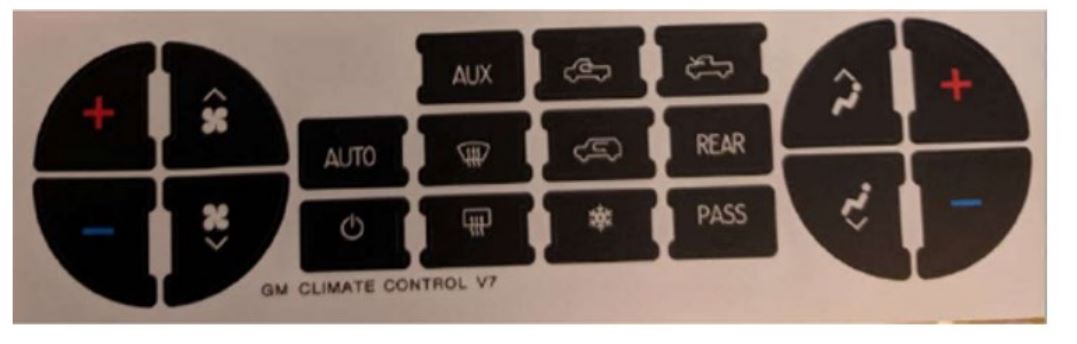

The copyright registrant alleged this copying design constituted copyright infringement. To settle that dispute, the parties worked out an “exclusive” license: the second-comer could sell the design on Amazon, and the registrant could keep selling it on eBay. The second comer/licensee assigned the exclusive license to a successor licensee, the defendant in this case. The registrant then offered the following sticker for sale on Amazon:

The registrant claimed this sticker design was not “proprietary because it was basically the factory control panel from a General Motors vehicle printed onto a sticker sheet.” Nevertheless, the successor licensee sent DMCA takedown notices to Amazon targeting the registrant’s stripped-down sticker. The registrant counternoticed each time. The wranglings caused the registrant’s sticker to be removed from Amazon for a total of 44 days in 2018 across several different incidents.

[Can you see why this case is so confusing? The copyright registrant is the target of takedown notices from a licensee who is trying to claim that its exclusively licensed rights are bigger than the copyright registrant thinks they are, so the copyright registrant basically has to talk down the scope of its registration. Also, I’m not sure who drafted the exclusive license, but it looks like their drafting made everyone’s life worse.]

The court found that the registrant sold about 8.3 stickers per day with an average profit of $8.46 per sticker set.

512(f) Analysis

The court lays out the legal principles (citing 11th Circuit law and this case in particular, though there aren’t major difference from 9th Circuit law):

because the DMCA Takedown Notice requires the complainant to certify that they have a good faith belief that infringement is occurring, if (in fact) they lack such a good faith belief, a misrepresentation occurs…a party that fails to consider fair use before submitting a DMCA Takedown Notice cannot form a reasonable good faith belief that infringement is occurring

Applying those principles, the court finds:

Plaintiff has proven by a preponderance of the evidence that (1) Defendant knowingly and materially misrepresented that copyright infringement occurred when Defendant submitted DMCA Takedown Notices of Plaintiff’s listing on November 19, 2018; (2) Amazon, the service provider, relied on those misrepresentation; and (3) Plaintiff was injured as a result of Defendant’s actions.

Before November 19, 2018, the previous takedown notices to Amazon didn’t violate 512(f) because the successor licensee didn’t have the requisite bad intent. The registrant’s attorney had numerous exchanges with the successor licensee’s attorney trying to explain the error of his ways, but the scienter bar is quite high. The court says that sending the August 2018 notice “was at least negligent (bordering on reckless)” but didn’t rise to the level of willful blindness. By November 1:

Defendant had knowledge of the facts described above, yet conducted no further investigation. Plus, Defendant knew that Plaintiff’s listing had been reinstated six days after it was taken down a second time. The Court finds that it was reckless of Defendant to submit the November 1, 2018, DMCA Takedown Notice, but that this takedown notice does not meet the high standard of willful blindness.

The court also credits the self-serving claim by the successor licensee that it considered fair use by comparing the works and evaluating if the works were being sold commercially or for other purposes. As I’ve mentioned before, 512(f) defendants will always say “I thought about fair use,” so that representation isn’t very enlightening, but the court was persuaded here.

What changed by November 19, 2018?

By this point, in addition to the information known to Defendant after the May DMCA Takedown Notice, Defendant knew that Plaintiff’s Amazon listing had been reinstated three times. Defendant had not tried to find out why Amazon kept reinstating Plaintiff’s listing. Defendant had not obtained the Deposit Design from the Copyright Office. And, the November 19 DMCA Takedown Notice acknowledged that many of the ASINs listed in the Notice were ones that had already been taken down and are “back up somehow.” All of these facts placed Defendant on actual notice that it was highly likely that, in fact, Plaintiff’s Sticker Sheet was not infringing the Subject Design. It also put Defendant on acute notice that there was a problem with its copyright infringement claim. Therefore, Defendant’s decision to not pursue information that would have helped confirm whether Plaintiff was infringing on a protected copyright constituted willful blindness.

I further find that by November 19, 2018, Defendant had a motive not to investigate further – filing DMCA Takedown Notices was less expensive and more immediate than pursuing a claim for copyright infringement on the merits. In making this finding I draw an adverse inference from Defendant’s failure to initiate litigation against Plaintiff…by November 19, 2018, Defendant was using the DMCA Takedown Notices to suppress a market competitor rather than to enforce a legitimate good faith claim of copyright infringement.

OK, I guess, but this is a reminder of how hard it is to win 512(f). The plaintiffs got three free bites at the apple before the fourth crossed over the line; and it mattered that the copyright work at issue here–stickers for car consoles–is so clearly subject to minimal or no copyright protection that no one realistically should have thought the sticker design was copyrightable, despite the registrant’s earlier settlement with the second comer. (For that reason, we can see how the Copyright Office’s registration of the sticker design with the background images was ultimately pernicious on the public by confusing everyone about the copyright scope, even though it’s a standard work for registration purposes). Plus, it mattered that the successor licensee never fully understood the scope of the exclusive license despite many, many (over?)assertions. I don’t think we’ll see many cases with this confluence of facts (assuming that they even survive an initial motion to dismiss, which most 512(f) cases can’t).

[UPDATE: I’ve been thinking more about this case and the judge’s move to a “willful blindness” standard is quite noteworthy. Putting aside the question of whether it’s actually consistent with the statutory scienter requirement (“knowingly materially misrepresents”), what it does in practice is open up the door for the judge to evaluate the defendant’s behavior objectively despite the Rossi case. This helps explain why this plaintiff won despite not having any “smoking gun” evidence or admissions that the plaintiff knew it was misrepresenting. Now, in this particular case, the judge could still claim that it was evaluating the plaintiff’s subjective beliefs because the judge didn’t believe the plaintiff’s testimony at trial based on body language, vocal inflections, etc. In other words, perhaps the judge could not have found for the plaintiff on summary judgment with the creditable evidence at that point; and perhaps the judge could not have found for the plaintiff if the judge concluded that the plaintiff was credible. The combination of the “willful blindness” standard, plus the possibility that the judge used an objective evaluation of the standard, could be a weak point on appeal.]

Financial and Other Implications

Hooray! The 512(f) plaintiff wins after 3 years of litigation and a bench trial. So what did it win? The registrant had its listings removed for a total of 5 days (based only on the November 19, 2018 notice). 8+ lost sticker sales a day at a profit of $8+ each x 5 days = $351.95. The registrant also claims he spent 40 hours working on this matter, but the court says it only should have required 3 hours to push back on the Nov. 19, 2018 notice, and the court values this time at $15/hr. So the court awards damages of $396.95…about the cost of a meal at the French Laundry, or not even 1 hour of the registrant’s time that it claims is worth $450/hr. Not exactly a financial windfall.

The court says that it will entertain motions for attorneys’ fees and costs. The registrant already submitted costs of $14k, which it seems likely to get if this result stands. I don’t see how the registrant gets much, if any, of its attorneys’ fees, however. The defense won with respect to three of the four DMCA notices, so the defense can justify its litigation decisions and has a good argument that it won a lot of the case. At most, the court would grant the attorneys’ fees that can be attributed just to the Nov. 19, 2018 notice, which should be a fraction of the total attorneys’ fees.

No money is moving yet because the successor licensee has already appealed the case to the 11th Circuit. I’m baffled why the successor licensee appealed. The appellate filing fee alone exceeds the awarded damages, so it’s obviously not about that money. Maybe it is worried about the attorneys’ fees? Maybe it plans to still send more takedown notices to Amazon to thwart its competitors? Even if so, the sales volume is low enough (the registrant is making a total of about $3k/yr in profits) that an appeal doesn’t seem financially prudent. I feel like I’m missing something here.

So kudos to the registrant for winning the 512(f) case. It achieved a rare outcome. But given the ridiculous economics of this still-ongoing litigation, don’t expect to see many plaintiffs pursuing the same course of action–and certainly not to a trial, which was financially illogical for both parties here.

Finally, how do you feel about Amazon’s role in this process? Was it simply a punching bag in the competitive battle between an overzealous successor licensee and a registrant/licensor? We could criticize its willingness to keep honoring the takedown notices; or we could celebrate that it honored the counternotices. Amazon is a key player in this litigation, but the court doesn’t address its responsibility at all.

Case Citation: Alper Automotive, Inc. v. Day to Day Imports, Inc., 2021 WL 5893161 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 3, 2021). The complaint filed in December 2018. The CourtListener page.

Other 512(f) Quick Links

Some other 512(f) cases I’ve not previously blogged:

* Paul Rudolph Foundation v. Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, 2021 WL 4482608 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 30, 2021):

Plaintiff alleges that Defendants knew that Defendant Wagner did not own the copyright to the images that Plaintiff posted on its social media channels, because Wagner abandoned the copyrights when he executed the Stipulation of Settlement, which dedicated the intellectual property rights of the images to the public domain. While the truth of these allegations must be ascertained at a later stage of litigation, they are sufficient as stated to survive a motion to dismiss.

* Signal 23 Television v. Anthony, 2020 WL 11206863 (N.D. Ga. Sept. 1, 2020). Plaintiff wins a default judgment under 512(f):

The Court also looked to the total loss in net revenue across all of Signal 23’s shows since Signal 23 explained during the hearing that YouTube took down Signal 23’s entire YouTube channel. This prevented Signal 23 from marketing for ABOUT HIM in addition to seven or eight other shows it had available for purchase on Vimeo. Using a similar calculation for the net monthly revenues of all of Signal 23’s shows would yield losses of more than five times the requested $35,000.00.

Further, § 512(f)’s broad damages language would permit Signal 23 to recover for other forms of harm it suffered, even though it did not ascribe a dollar value to such harm. During the hearing, Signal 23 stated that its calculation does not take into account the loss of its fan base; Signal 23’s ability to advertise and grow its audience; the value of the time and effort spent responding to issues such as reimbursements to customers who paid for episodes on Vimeo that were then taken down; the time and effort spent rebuilding its audience after Vimeo, YouTube, and Facebook restored its access to those platforms; the lost revenue from advertisements on its YouTube channel while the channel was disabled; and, losses from reduced sales on Vimeo after 2017 because of Defendants’ misrepresentations, which continue to plague Signal 23 today.

Accordingly, the evidence presented by Signal 23 shows that it suffered harm of at least $35,000.00 in damages stemming from Defendants’ violations of the DMCA.

* Tierra Caliente Music Group SA v. Serca Discos, Inc., 2019 WL 13109708 (S.D. Tex. Aug. 14, 2019):

Plaintiffs allege that YouTube removed the YouTube Videos from user Remex’s account upon receipt of Serca’s Takedown Notices, which allegedly made the “fraudulent” claim that Serca held the copyrights to the content included in the Videos. Plaintiffs’ ensuing claim that Serca violated § 512(f) (and in particular, subsection (1)), draws from the plain language of the statute, which allows an “alleged infringer” to recover against “any person” who “knowingly materially misrepresents” in a takedown notice “that material or activity is infringing.” Plaintiffs’ pleading offers a plausible theory as to why it enjoys the status of an “alleged” infringer with standing to sue Serca: that the Exclusivity Agreement and subsequent assignments gave Plaintiffs the exclusive rights to distribute and administer rights to La Leyenda songs and videos recorded under the Agreement, and that Serca’s claim to hold the copyrights to the content of the YouTube Videos, as communicated to YouTube through the Takedown Notices, was “fraudulent.” Plaintiffs have stated a claim against Serca within the meaning of § 512(f), and Serca’s Rule 12 Motion must be denied.

* BMaddox Enterprises LLC v. Oskouie, 2021 WL 3675072 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 18, 2021)

Plaintiff claims that he was injured by Oskouie’s misrepresentations in two counternotices sent to the DMCA, on June 20, 2016 and January 23, 2017. In both cases, Oskouie represented to the service provider that Plaintiff lacked the copyright to the material in question. The Court notes, however, that Plaintiff did not register his copyrights in his website until more than six months after Oskouie sent his second challenged notice. Plaintiff has not alleged, or adduced any evidence, that it owned a copyright in this website other than those embodied in those registrations. Consequently, it has not established that Oskouie’s statements were false when made, let alone that Oskouie did not have a good-faith belief that Plaintiff lacked copyright protection over those materials. As a result, the Court cannot determine that Oskouie is liable, as a matter of law, under the DMCA. The motions for default judgment and summary judgment are therefore denied.

* Doggie Dental, Inc. v. Shahid, 2021 WL 4582112 (N.D. Cal. June 17, 2021)

In Defendant’s DMCA Counter Notice, purportedly issued under the authority of 17 U.S.C. § 512, Defendant stated “that material or activity was removed or disabled by mistake or misidentification.” Plaintiff contends that this was a misrepresentation, because Defendant knew that he did not possess a valid and enforceable copyright in the infringing material. In fact, Plaintiff holds the exclusive rights to the Photographs and did not consent to Defendant’s use. Plaintiff claims that it was injured by Defendant’s knowing and material misrepresentations and willful actions portraying Plaintiff’s Device and Photographs as belonging to Defendant. These damages include lost profits and goodwill, monetary damage, and damage to reputation. Accordingly, Plaintiff states a claim for misrepresentation.

Prior Posts on Section 512(f)

* Satirical Depiction in YouTube Video Gets Rough Treatment in Court

* 512(f) Preempts Tortious Interference Claim–Copy Me That v. This Old Gal

* 512(f) Claim Against Robo-Notice Sender Can Proceed–Enttech v. Okularity

* Copyright Plaintiffs Can’t Figure Out What Copyrights They Own, Court Says ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

* A 512(f) Case Leads to a Rare Damages Award (on a Default Judgment)–California Beach v. Du

* 512(f) Claim Survives Motion to Dismiss–Brandyn Love v. Nuclear Blast America

* 512(f) Claim Fails in the 11th Circuit–Johnson v. New Destiny Christian Center

* Court Orders Rightsowner to Withdraw DMCA Takedown Notices Sent to Amazon–Beyond Blond v. Heldman

* Another 512(f) Claim Fails–Ningbo Mizhihe v Doe

* Video Excerpts Qualify as Fair Use (and Another 512(f) Claim Fails)–Hughes v. Benjamin

* How Have Section 512(f) Cases Fared Since 2017? (Spoiler: Not Well)

* Another Section 512(f) Case Fails–ISE v. Longarzo

* Another 512(f) Case Fails–Handshoe v. Perret

* A DMCA Section 512(f) Case Survives Dismissal–ISE v. Longarzo

* DMCA’s Unhelpful 512(f) Preempts Helpful State Law Claims–Stevens v. Vodka and Milk

* Section 512(f) Complaint Survives Motion to Dismiss–Johnson v. New Destiny Church

* ‘Reaction’ Video Protected By Fair Use–Hosseinzadeh v. Klein

* 9th Circuit Sides With Fair Use in Dancing Baby Takedown Case–Lenz v. Universal

* Two 512(f) Rulings Where The Litigants Dispute Copyright Ownership

* It Takes a Default Judgment to Win a 17 USC 512(f) Case–Automattic v. Steiner

* Vague Takedown Notice Targeting Facebook Page Results in Possible Liability–CrossFit v. Alvies

* Another 512(f) Claim Fails–Tuteur v. Crosley-Corcoran

* 17 USC 512(f) Is Dead–Lenz v. Universal Music

* 512(f) Plaintiff Can’t Get Discovery to Back Up His Allegations of Bogus Takedowns–Ouellette v. Viacom

* Updates on Transborder Copyright Enforcement Over “Grandma Got Run Over by a Reindeer”–Shropshire v. Canning

* 17 USC 512(f) Preempts State Law Claims Over Bogus Copyright Takedown Notices–Amaretto v. Ozimals

* 17 USC 512(f) Claim Against “Twilight” Studio Survives Motion to Dismiss–Smith v. Summit Entertainment

* Cease & Desist Letter to iTunes Isn’t Covered by 17 USC 512(f)–Red Rock v. UMG

* Copyright Takedown Notice Isn’t Actionable Unless There’s an Actual Takedown–Amaretto v. Ozimals

* Second Life Ordered to Stop Honoring a Copyright Owner’s Takedown Notices–Amaretto Ranch Breedables v. Ozimals

* Another Copyright Owner Sent a Defective Takedown Notice and Faced 512(f) Liability–Rosen v. HSI

* Furniture Retailer Enjoined from Sending eBay VeRO Notices–Design Furnishings v. Zen Path

* Disclosure of the Substance of Privileged Communications via Email, Blog, and Chat Results in Waiver — Lenz v. Universal

* YouTube Uploader Can’t Sue Sender of Mistaken Takedown Notice–Cabell v. Zimmerman

* Rare Ruling on Damages for Sending Bogus Copyright Takedown Notice–Lenz v. Universal

* 512(f) Claim Dismissed on Jurisdictional Grounds–Project DoD v. Federici

* Biosafe-One v. Hawks Dismissed

* Michael Savage Takedown Letter Might Violate 512(f)–Brave New Media v. Weiner

* Fair Use – It’s the Law (for what it’s worth)–Lenz v. Universal

* Copyright Owner Enjoined from Sending DMCA Takedown Notices–Biosafe-One v. Hawks

* New(ish) Report on 512 Takedown Notices

* Can 512(f) Support an Injunction? Novotny v. Chapman

* Allegedly Wrong VeRO Notice of Claimed Infringement Not Actionable–Dudnikov v. MGA Entertainment