2024 Internet Law Year-in-Review

My ranking of the top 10 Internet Law developments of 2024.

10) X/Twitter Embraces Partisan Bias. For years, MAGA has claimed that Internet company employees are liberals and therefore surely moderate content to favor their preferred team (the Democrats) and hurt their rivals (the Republicans). This is such a foundational tenet of MAGA discourse that it was one of the few substantive platforms the Republican party adopted running up to the 2024 Presidential election.

As the expression goes, every accusation is an admission. The reason Republicans suspect a partisan editorial skew is because that’s exactly what they would do if they controlled the reins, and they assume that everyone else plays the game their way.

Empirically, MAGA’s presumptions were wrong. For years, the empirical literature has consistently refuted the allegations of “liberal bias” by Internet companies. Instead, the literature has shown that Internet companies sometimes affirmatively favored MAGA content or adopted facially neutral policies that implicitly benefited MAGA content.

But MAGA got one thing right: some social media owners would find the temptation to embrace partisanship irresistible.

Specifically, when a MAGA stan (Musk) got control over an Internet company (Twitter), guess what happened? Musk intentionally turned X/Twitter into a MAGA promotion engine, adopting putatively “neutral” policies that preferenced MAGA voices (e.g., the blue check program) and making partisan interventions such as Musk’s personal pro-MAGA tweeting and manual targeting of MAGA-disfavored accounts.

MAGA has also complained that the government improperly pressured social media to make content moderation decisions (the so-called “censorship-industrial complex”). Those fears were routinely overstated, but look where we stand now: very soon, Musk and Trump will both wear dual hats as government employees and owners of social media. (There are supposed to be conflicts-of-interest laws that prevent this, but America has become a post-conflicts kleptocracy). So when Musk and Trump make decisions, whether as government employees or owners of their social media, their actions will be a toxic brew of self-interest, partisanship, and state action. If MAGA is worried about too much government interference with social media editorial decisions, THIS IS WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE. 👉👈

All told, Musk single-handedly actualized all of the false allegations that MAGA had previously made about partisan bias in social media–and proved that other social media’s historical biases came nowhere close to Musk’s partisan capture.

From my perspective, Musk has the discretion to run his social media service as he sees fit (subject to conflicts-of-interest/state action restrictions once he becomes a government actor). His actions may be troubling and ill-advised, but regulatory limits would be impermissible censorship.

Meanwhile, Twitter’s marketplace decline has demonstrated (once again) that market mechanisms–including users and advertisers voting with their “feet”–still carry a potent sting online. Seeing X/Twitter’s self-caused implosion acts as a fact-check on everyone who argued that Twitter was creating antitrust problem because it had an unassailable market position in social media (because network effects something something). The exodus of users and advertisers from Twitter proved those Twitter-&-antitrust “hot takes” were always the pundit’s censorial or partisan fever dreams.

Finally, my Twitter account is still active, but I haven’t posted there in many months. I’ve instead made Bluesky my primary social media home. FOLLOW ME THERE!

9) Supreme Court Tamps Down on Jawboning and Government Social Media Lawsuits. The Supreme Court is taking a steady stream of Internet Law cases, a trend that will continue for some time. Tomorrow, the Supreme Court will hear the TikTok ban, and Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton regarding mandatory age authentication.

In Lindke and O’Connor-Ratcliff, the court addressed when a government employee’s social media account becomes state action. The court’s holding ensures that most social media accounts operated by government employees will not qualify as state action, even if the accountholder is loudly boasting about their official government work and engaging constituents to discuss it. I haven’t done a comprehensive analysis of the post-Lindke rulings, but anecdotally I’m seeing a lot of defense wins.

In Murthy, the court addressed when government contacts with social media constitute censorial “jawboning.” The court resolved the matter on standing grounds, but in a way that made it harder for plaintiffs to win those cases as well. The court did address substantive jawboning issues in the NRA v. Vullo case, but the facts there were pretty egregious. Most social media conversations with the government come nowhere close to the Vullo level.

8) Courts to Trademark Owners: Stop Suing Over Competitive Keyword Ads. I can’t believe trademark owners are still suing keyword advertisers over competitive keyword ads, and neither can the courts. Two major appellate courts pushed back on trademark owners in 2024. The Second Circuit said that the trademark owner can’t compare its trademark against the purchased keyword, and the resulting absence of mark similarity decisively favors the advertiser. Not to be outdone, the Ninth Circuit held that three of the four Network Automation expedited confusion factors for keyword ad cases should be interpreted to categorically favor the defense, essentially making it impossible for trademark owners to win. The writing is on the wall: competitive keyword ad cases are a dead-end.

The news was only slightly soured by a concurrence in the Ninth Circuit opinion, which said that buying keyword ads shouldn’t be a use in commerce (which, if true, would categorically end all competitive keyword ad cases) but selling keyword ads could be a use in commerce. The last thing we need is to reignite the “use in commerce” debates that raged 15 years ago, and some trademark owners would be willing to take a flyer on suing Google even though Google functionally resolved its liability a dozen years ago.

7) The Rise–and Fall?–of Generative AI. We’re still figuring out how to use Generative AI in our society, but it’s unclear that Generative AI will remain available to help us. Generative AI faces an onslaught of legal threats. Copyright owners are hoping to take down Generative AI (as indefatigably catalogued by my colleague Ed Lee). If any of those lawsuits succeed, they pose a potential existential threat to the entire industry. Worse, state legislatures are also going ham to regulate every aspect of Generative AI, as if they can freely override the model-makers’ editorial discretion. It remains to be seen if the First Amendment will invalidate some or all of those efforts. If the constitution doesn’t adequately check the legislatures, Generative AI is destined for regulatory oblivion.

6) Ninth Circuit Drama on Section 230. The Third Circuit set the pace this year for awful Section 230 rulings (discussed below), but the Ninth Circuit wasn’t far behind.

In Calise v. Meta, the Ninth Circuit addressed the publisher/speaker prong of the 230 prima facie defense. The court said that rather than looking at the names of the claims, the court should look at what “duties” the claim would impose. This all sounds logical enough, but “duties” is just an empty vessel for courts to insert their normative and doctrinal biases. In other words, the court took what used to be an easy prong–all claims were publisher/speaker claims unless they were the statutory exclusions–and issued a blank check to judges to do whatever the hell they want with Section 230 cases.

In Bride v. YOLO, the Ninth Circuit extended the Calise “duties” approach to suggest that all promise-based claims are categorically insulated from a Section 230 defense. That outcome conflicts with both prior Ninth Circuit precedent and the jurisprudence in the California state courts, and at least one lower-court judge has already pushed back on it. If the YOLO promise-based exclusion to Section 230 stands up, plaintiffs will have no problem tendentiously parsing a defendant’s site disclosures to find something–anything–as the anchor for a promise-based claim that bypasses Section 230.

5) Social Media “Addiction.” During the pandemic, the Internet became the critical lifeline for students: it was their school, their source of entertainment, their social outlet, their “Third Place.” Unsurprisingly, as the pandemic partially abated, children kept using the Internet heavily, but now they are being accused of being “addicted” to the Internet. No doubt some children (and adults) overuse the Internet to an unhealthy degree, but there is also no clinical diagnosis of “Internet addiction,” so the term is imprecise at best.

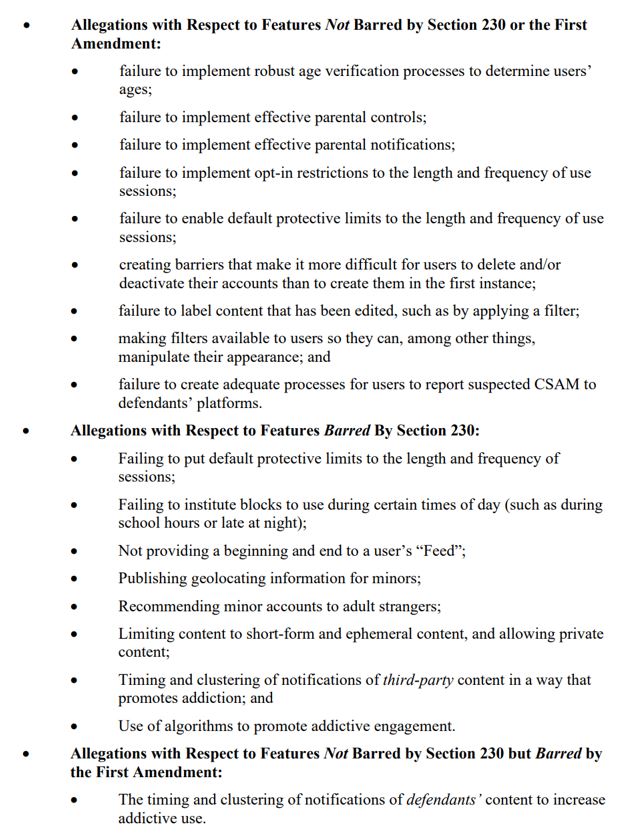

The battles over social media addiction are taking place in both the courts and legislatures. In the courts, there are massive cases pending in California state and federal courts. I think this chart gives you a flavor for how those cases are going:

What a mess. These cases definitely will be appealed, and I’m waiting to see how the appeals fare before drawing any conclusions.

Meanwhile, state legislatures are getting into the action, including New York’s SAFE for Kids Act and California’s SB 976, which partially survived the First Amendment challenge. These legal challenges will also head to appeals courts, also with uncertain fates.

The US Senate passed the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) despite it being a terrible bill, but fortunately the bill stalled in the House. I’m sure Congress will pursue multiple similar bad bills in the new Congressional term.

The regulatory crackdown is taking place beyond the US too. Australia categorically banned all under-16s from social media, and the UK implemented its Online Safety Act (and in response, the Internet shrunk immediately). These foreign laws aren’t subject to First Amendment limits, either.

I will harshly criticize these so-called child online safety laws in my Segregate-and-Suppress article.

I will harshly criticize these so-called child online safety laws in my Segregate-and-Suppress article.

4) The Third Circuit Unilaterally Repeals Section 230. Many judges have turned against Section 230, so we’re seeing a proliferation of jurisprudential experimentation with ideas of how to gut it. But I don’t think anyone realistically expected to succeed with the argument that the plaintiffs made to the Third Circuit in the Anderson v. TikTok case. The Third Circuit said that the Moody case (discussed below) overturned 28 years of Section 230 jurisprudence. Instead of the longstanding interpretations of Section 230, the court held that because the First Amendment protects social media’s editorial decisions towards third-party content, all third-party content magically transforms into first-party content for Section 230 purposes.

This is spectacularly bad reasoning. I’ll highlight two problems. First, the Moody majority opinion never once mentioned Section 230, so the Third Circuit is taking the position that the Supreme Court overturned over 1,000 Section 230 cases sub silento. Hmm. Second, Moody interpreted the First Amendment, not legislation that exists alongside the First Amendment. It is entirely logical and consistent that First Amendment protection for editorial decisions has no bearing on interpretations of the Section 230 statute.

This is spectacularly bad reasoning. I’ll highlight two problems. First, the Moody majority opinion never once mentioned Section 230, so the Third Circuit is taking the position that the Supreme Court overturned over 1,000 Section 230 cases sub silento. Hmm. Second, Moody interpreted the First Amendment, not legislation that exists alongside the First Amendment. It is entirely logical and consistent that First Amendment protection for editorial decisions has no bearing on interpretations of the Section 230 statute.

Will other courts follow this misguided reasoning? Will the Supreme Court intervene to explain the Moody opinion to the Third Circuit? Unless and until it gets fixed, the Third Circuit’s ruling casts a dark shadow over all of Section 230 jurisprudence.

3)  The Implications of Trump’s Election for Section 230. There are many reasons to be concerned about Trump 2.0, but for this post, I’m going to focus solely on its implications for Section 230.

The Implications of Trump’s Election for Section 230. There are many reasons to be concerned about Trump 2.0, but for this post, I’m going to focus solely on its implications for Section 230.

If you recall, Trump 1.0 tried to repeal Section 230. In May 2020, Trump issued an anti-230 executive order, but that was pointless because the executive branch can’t unilaterally amend legislation passed by Congress. (However, the EO did stir up MAGA against Section 230, a pathogen that continues to infect Section 230 discussions to this day). Then, in his lame duck session of Congress, Trump vetoed raises for the military because the bill didn’t also repeal Section 230. (What do military raises and Section 230 have to do with each other? Only a “very intelligent person” like Trump can connect those dots). Even Trump’s loyalists couldn’t abide by this non-sequitur, so Congress overrode his veto, gave military personnel raises, and left Section 230 in place.

Trump 2.0 will be different in important ways. First, the Republicans have a federal trifecta (majorities in both legislative chambers plus the presidency). Second, Section 230’s reputation has continued to slide. As a result, there is almost no member of Congress who would vote against a Section 230 repeal, Democrat or Republican. A Section 230 repeal bill would pass with supermajorities in both chambers–the Senate filibuster would not save it. Literally all Trump has to do is ask. Third, if Congress doesn’t repeal Section 230, Trump has appointed chairs of the FCC and FTC who have both railed against Section 230 and the “censorship-industrial complex.” This activates two powerful agencies to do what they can to undermine Section 230–even unconstitutional actions that exceed the agencies’ statutory authorities. There are very few scenarios where Section 230 survives these attacks and retains any structural integrity.

Trump 2.0 will be different in important ways. First, the Republicans have a federal trifecta (majorities in both legislative chambers plus the presidency). Second, Section 230’s reputation has continued to slide. As a result, there is almost no member of Congress who would vote against a Section 230 repeal, Democrat or Republican. A Section 230 repeal bill would pass with supermajorities in both chambers–the Senate filibuster would not save it. Literally all Trump has to do is ask. Third, if Congress doesn’t repeal Section 230, Trump has appointed chairs of the FCC and FTC who have both railed against Section 230 and the “censorship-industrial complex.” This activates two powerful agencies to do what they can to undermine Section 230–even unconstitutional actions that exceed the agencies’ statutory authorities. There are very few scenarios where Section 230 survives these attacks and retains any structural integrity.

I’ve heard some chatter that maybe Trump will go easy on Secton 230. After all, he has billions of dollars tied up in Truth Social, which benefits from Section 230. (Of course, in a pre-MAGA America, such stock holdings would be an impermissible ethics conflict, but again, no one seems to care about conflicts any more). And then there’s Musk, the power pulling Trump’s strings, who also has billions tied up in a social media entity that benefits from Section 230. On the other hand, the fact that Musk has voluntarily lit tens of billions of dollars on fire through his mismanagement of X/Twitter seems to suggest he’s willing to lose it all. Finally, newly emboldened MAGA stans Zuckerberg and Bezos have billions of dollars of wealth tied up in services that benefit from Section 230 and are currying favor with Trump by throwing million-dollar checks at his inauguration. Maybe they will bend Trump’s ear favorably to preserve their wealth?

To anyone who thinks that any of these factors will save Section 230, I wonder: WHAT TIMELINE ARE YOU LIVING IN? I am living in the 2025 MAGA timeline where nothing makes sense and Trump can and will exercise raw power to achieve the worst possible outcomes. He certainly cares about his personal wealth, but he will extract so many profits from his presidency that he won’t care if Truth Social gets vaporized.

As a result, Section 230 is on the extinction watch list in 2025. I will be shocked if it survives to see 2026. If you don’t already have a Section 230 tattoo, now is probably not the time to get one.

As a result, Section 230 is on the extinction watch list in 2025. I will be shocked if it survives to see 2026. If you don’t already have a Section 230 tattoo, now is probably not the time to get one.

2) Congress Banned TikTok. Can It? The old model of censorship was to ban certain categories of speech. The modern model of censorship is to ban entire speech venues. Bigger censorship payoffs for the same amount of legislative work.

Pursuing this line of thinking, Congress banned TikTok. The TikTok ban was a remarkable demonstration of bipartisan cooperation–the kind that can be produced in the modern era only by whipping up a toxic brew of Sinophobia, pretextual national security concerns, and censorship.

Given that the ban nukes a speech venue used by 170M Americans with the express legislative goal of suppressing political viewpoints that support China, surely the ban MUST be unconstitutional, right? Not to the D.C. Circuit, which found a way to bless the ban even if strict scrutiny applied. It didn’t seem like the D.C. Circuit applied a very strict version of strict scrutiny, especially when it came to credulously accepting Congress’ weak sauce about national security. The whole decision also seemed to run counter to the lessons the Supreme Court had just taught months ago in the Moody decision (discussed below). So will the Supreme Court hand legislatures the power to sprinkle some “national security” pixie dust over laws that ban speech venues and eviscerate the First Amendment at scale? We’ll find out very, very soon.

Given that the ban nukes a speech venue used by 170M Americans with the express legislative goal of suppressing political viewpoints that support China, surely the ban MUST be unconstitutional, right? Not to the D.C. Circuit, which found a way to bless the ban even if strict scrutiny applied. It didn’t seem like the D.C. Circuit applied a very strict version of strict scrutiny, especially when it came to credulously accepting Congress’ weak sauce about national security. The whole decision also seemed to run counter to the lessons the Supreme Court had just taught months ago in the Moody decision (discussed below). So will the Supreme Court hand legislatures the power to sprinkle some “national security” pixie dust over laws that ban speech venues and eviscerate the First Amendment at scale? We’ll find out very, very soon.

1) Supreme Court Rallies Behind Online Free Speech (For Now)–Moody v. NetChoice. In a stirring majority opinion written by Justice Kagan, the Supreme Court issued a strong endorsement that social media services are publishers that qualify for First Amendment protection.

1) Supreme Court Rallies Behind Online Free Speech (For Now)–Moody v. NetChoice. In a stirring majority opinion written by Justice Kagan, the Supreme Court issued a strong endorsement that social media services are publishers that qualify for First Amendment protection.

The decision dramatically undermined the foundation of many of the online censorship laws being adopted around the country, but it’s too early to celebrate the First Amendment’s protection for online free speech yet. First, the opinion remanded the cases for reconsideration, so the cases will end up back on the Supreme Court docket again, with uncertain prospects. Second, the coalition assembled by Justice Kagan could be fragile and could fall apart in future cases. Third, the forces of censorship aren’t exactly chastened. They are manufacturing censorship laws faster than the courts can enjoin them. Will the censors win by default, simply by flooding the zone?

For more on Moody, see my recap of the Supreme Court decision.

* * *

Honorable Mentions

Other things that caught my eye this year:

SAD Scheme. It’s been nice to see some judges finally pushing back on the scheme.

IAPs and Copyright Infringement. The news continues to be awful for IAPs being legally responsible for not terminating the Internet access of possible recidivist downloaders.

Pixel Cases. If you haven’t been watching the litigation tsunami over Meta Pixels, it’s been a sight to behold. Last time I checked, I think there were 150 pixel rulings in Westlaw. The early rounds have not gone well for the defendants in many cases. Some coverage from this year.

Suing a DAO. A DAO could be a partnership that exposes many/all participants to vicarious liability for the DAO’s actions. Yikes!

Tattoos and Copyrights. 2024 brought a couple interesting rulings limiting copyright enforcement over tattoos. Alexander v. Take Two, Hayden v. 2K.

France’s Prosecution of Telegram Principal. There was a lot of angst over France prosecuting Pavel for users’ content on Telegram, but personal liability for UGC is nothing new in Europe–or elsewhere for that matter.

Copyright and Bananas. A banana duct-taped to the wall–a work entitled Comedian–by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, sold at auction for $6.2M to a cryptobro who then ate the most expensive banana ever. This cash windfall was only possible because an 11th Circuit ruling held that Cattelan hadn’t committed copyright infringement of precedent works involving the duct-taping of a banana and an orange to the wall.

Privacy Lawyers May Be Why We Can’t Have Nice Things. If you’re a privacy hammer, everything looks like a privacy nail. That’s how we get some jaw-dropping privacy lawsuits seeking to kick socially beneficial offerings out of the market, including game avatars, augmented reality, and most shockingly, anti-CSAM filters.

Emoji Law Cases Are 👍. An important ruling from the Saschakewan Court of Appeals, affirming that a thumbs-up emoji could constitute assent to a contract with tens of thousands of dollars of economic consequence.

California Legislature’s Remarkable Track Record of Censorship. I didn’t prepare a comprehensive list of all of the times the courts have declared California’s Internet Laws unconstitutional, but I took special note of the Ninth Circuit’s rejection of the Age-Appropriate Design Code.

California Legislature’s Remarkable Track Record of Censorship. I didn’t prepare a comprehensive list of all of the times the courts have declared California’s Internet Laws unconstitutional, but I took special note of the Ninth Circuit’s rejection of the Age-Appropriate Design Code.

How will the California legislature react to the repeated judicial rejections of its efforts?

What is Trespass to Chattels Online? The trespass to chattels doctrine has become unteachable. I taught the X v. Bright Data ruling from May in my Internet Law course this Fall, only to have Judge Alsup whipsaw everyone in a November 2024 ruling. How can a server delimit access? What constitutes chattel harm? What do cases like hiQ and Van Buren stand for? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

I note a particularly odd ruling from 2021 in Best Carpet Values v. Google, a lawsuit over web page framing where the court held that trespass to chattels doesn’t actually require any chattels, which makes it just…trespass of, um, something? Trespass to butthurt feelings maybe? Fortunately, the Ninth Circuit reversed that ruling, reinforcing that you need a chattel to have trespass to chattels. Then again, we got this wacky ruling in a pixel case holding that placing a pixel or cookie could constitute trespass to chattels, so we are still not at a doctrinal equilibrium yet.

* * *

Previous year-in-review lists from 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, and 2006. John Ottaviani and I previously listed the top Internet IP cases for 2005, 2004 and 2003.

* * *

My publications in 2024:

Advertising Law: Cases and Materials (with Rebecca Tushnet), 7th edition

Internet Law: Cases & Materials, 15th edition

Generative AI is Doomed, Marq. IP & Tech. L. Rev. (in press). A shortened version republished in Marquette Lawyer, Fall 2024, at 16

“Speech Nirvanas” on the Internet: An Analysis of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Moody v. NetChoice Decision, Cato Supreme Court Review 2023-24, 125-155

Assuming Good Faith Online, Journal of Online Trust & Safety (Vol. 2, No. 2, Feb. 2024)

How the DMCA Anticipated the DSA’s Due Process Obligations, VerfBlog, Feb. 20, 2024 (with Sebastian Schwemer). Republished in From the DMCA to the DSA ebook (Joao Pedro Quntais ed. 2024)

Advocacy Work

Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton, amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of Free Speech Coalition, September 2024 (with Amber Greenaway of Bondurant Mixson & Elmore, LLP)

Neville v. Snap, amicus brief to the California Court of Appeals in support of review, March 2024 (primarily written by Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati)

NetChoice LLC v. Bonta, amicus brief to the Ninth Circuit in support of NetChoice, February 2024

Pingback: Links for Week of January 10, 2025 – Cyberlaw Central()