2023 Internet Law Year-in-Review

My roundup of the top Internet Law developments of 2023:

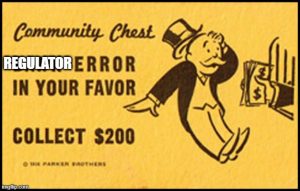

10) California court bans targeted advertising (?). Regulators have sought to suppress online targeted advertising for years, with only minimal success. Then, in Liapes v. Facebook, a California appeals court shocked the advertising community by suggesting that using common demographic criteria for ad targeting, such as age or gender, may violate California’s anti-discrimination law. The court got there by collapsing the distinction between (1) businesses discriminating against buyers based on their identity, and (2) advertisers allocating scarce advertising dollars to highlight their offerings to the most interested consumers. Advertisers must prioritize their advertising spend because advertisers can’t afford to educate the entire world about their offerings; nor would the widespread bombardment of untargeted ads benefit consumers. I hope that further proceedings in the case fix the court’s pretty obvious error–but that fix won’t come from the California Supreme Court, which unfortunately denied the petition for review.

9) Musk destroys Twitter. Say what you will about Musk, but he is making an important contribution to science. He has turned Twitter into a multi-billion dollar A/B experiment about the value of content moderation. Before Musk’s acquisition of Twitter, commentators would often assert that it wasn’t profitable to severely reduce or turn off content moderation because users and advertisers wouldn’t tolerate it. However, those arguments were more theoretical than empirical; there weren’t a lot of high-profile examples of a mass-market consumer service deploying this strategy. Musk has bridged that gap. Musk has progressively dismantled Twitter’s content moderation efforts, brought back suspended/terminated but noxious users, capriciously banned legitimate users (including journalists), blown up the identity verification (“blue check”) system and fostered inauthentic accounts, and personally engaged in countless incidents of asshattery.

These moves have devastated Twitter’s employees, Twitter’s investors, Musk’s personal finances, Musk’s personal reputation, and once-passionate Twitter users. Twitter has turned into a place you don’t want to be seen (i.e., seriously, are you still posting THERE???) unless you are a Nazi or wannabe. In turn, advertisers have fled Twitter. Going forward, any time someone wants to extol the virtues of content moderation, all they have to do is say “Twitter” and everyone will nod their head in silent tacit agreement.

8) The SAD Scheme is replacing the notice-and-takedown scheme. The venerable IP notice-and-takedown scheme is being replaced by the SAD Scheme, where rightsowners quietly obtain ex parte TROs that target online marketplace accounts. Thousands of SAD Scheme lawsuits have been filed because the TROs take the online merchant off the marketplace entirely and usually extract some cash. Why wouldn’t rightsowners prefer this option over the Sisyphean tedium of sending item-by-item takedown notices?

8) The SAD Scheme is replacing the notice-and-takedown scheme. The venerable IP notice-and-takedown scheme is being replaced by the SAD Scheme, where rightsowners quietly obtain ex parte TROs that target online marketplace accounts. Thousands of SAD Scheme lawsuits have been filed because the TROs take the online merchant off the marketplace entirely and usually extract some cash. Why wouldn’t rightsowners prefer this option over the Sisyphean tedium of sending item-by-item takedown notices?

Unfortunately, to get these benefits, rightsowners and the courts necessarily cut some due process corners. This inevitably produces SAD Scheme victims, who have their legitimate businesses and personal lives thrown into a tailspin. The public got a taste of the collateral damage when Luke Combs admitted that his enforcement team had used the SAD Scheme to upend the life of an enthusiastic fan. Behind that publicized incident are hundreds or thousands of additional stories of personal devastation. #StopTheSADScheme.

7) Governments loot Google and Facebook under the pretense of “saving” journalism. The term “link taxes” refer to the government compulsion of large Internet services, such as social media or search engines, to pay news media for indexing and publishing their headlines and links.

7) Governments loot Google and Facebook under the pretense of “saving” journalism. The term “link taxes” refer to the government compulsion of large Internet services, such as social media or search engines, to pay news media for indexing and publishing their headlines and links.

To me, the term “link tax” is a misnomer. It’s not a tax. The money doesn’t go to the government. Instead, it’s a compelled wealth transfer from some members of one industry (Google and Facebook, usually) to some members of another industry (journalist operations, whatever that means, or organizations that claim to be). Such mandatory wealth transfers between private parties should be way outside the zone of legitimate governmental authority. But because the news media is failing (accelerated by vulture funds like Alden Capital) and everyone is techlashing, this policy approach has gotten way more consideration than it deserves.

Canada’s C-18 provides a prime case study. Facebook turned off the links that would trigger compensation, because these links don’t generate much value for Facebook. Facebook’s exit devastated independent Canadian publishers, who begged the government to reverse its policy. Worse, the law created a major public safety issue when wildfires ravaged Canada but Facebook’s withdrawal hindered communication about the emergency.

The Canadian experiences proved several points that “link tax” opponents have been highlighting: the links produce social value that is not considered in the compelled wealth transfers; the tax can exceed the value of the links to the services, accelerating exits; and the links create value to news media, so the payments flow in the wrong direction.

Despite Canada’s experience, the California legislature continues to consider the compelled wealth transfers. Incredible.

6) Jawboning. Governments constantly pressure Internet services’ editorial decisions. Some of this pressure represents beneficial dialogues between the public and private sector, such as efforts to advance public health and safety. Other pressure is clearly censorial, such as when government officials seek to dictate editorial decisions to support their partisan goals. The line between the productive and condemnable government engagement is murky and fluid.

On July 4, 2023, a federal judge declared FREEDOM from government censorship of Internet services. Well, actually, the opinion only focused on the government’s flagging of some #MAGA issues to Internet services, typically to reduce threats to public health and safety. Shockingly, the judge ordered the executive branch to stop talking to Internet services about certain issues. The issue is now before the Supreme Court, though I doubt the Supreme Court’s resolution will satisfy anyone.

5) Europe’s anti-Internet initiatives (DSA and UK Online Safety Act). European regulators have increasingly asserted control over the Internet, with censorship as the predictable result.

In 2023, the EU launched its Digital Services Act. The DSA is a command-and-control style regulation, micromanaging services’ editorial operations and decisions. To me, the DSA resembles how governments regulate banks, with the same level of regulatory sensitivity towards the speech implications (i.e., none). DSA supporters promised that the DSA couldn’t be weaponized as a censorship tool. That was immediately disproven.

The UK Online Safety Act represents an even more holistic and comprehensive regulatory control over publication decisions. I expect many regulated entities will exit the UK UGC industry because it’s too costly/risky to play by those rules. If so, as I predicted in 2019, the UK Online Safety Act will accelerate the end of Web 2.0 and the transition to a Web 3.0 filled with paywalled professionally produced content instead of free-to-consume UGC.

4) Social media “defective design” lawsuits go forward. Many empirical studies have proven that social media materially benefits many, though not all, young users. Ideally, social media services should be studying this data to strike balances between various subpopulations. Instead, plaintiffs’ lawyers are marshaling legal theories built for an industrial era to cut short those nuanced deliberations. Following the Lemmon v. Snap opinion, plaintiffs are–with some preliminary successes–arguing that social media services defectively design how they gather, organize, and disseminate third-party content. If successful, these cases would place judges in the role of deciding how social media services should publish content–even if the outcomes will HURT some users.

3) Supreme Court dodges Section 230. The Supreme Court was positioned to interpret Section 230 for the first time in the Gonzalez v. Google case. Instead, the court punted and remanded the case. Don’t worry: the Supreme Court will have many future opportunities to muck up Section 230 and the Internet.

2) Legislators embrace faux “child safety” measures. US regulators are eager to do SOMETHING about the Internet, regardless of whether or not their interventions would solve problems or make things worse. This doomspiral cranked into high gear in 2023, as legislatures around the country passed “save kids online” laws that are unconstitutional–and harmful to kids and adults. In particular, age authentication mandates are riddled with unavoidable privacy and security concerns; they also make it harder to navigate the Internet and create an authentication infrastructure that censors and authoritarians will find easy to weaponize in the future.

Despite these obvious issues, the privacy community has been conspicuously quiet about age authentication. Why? For some community members, their techlash animus overrides all other considerations. Yet, all of the hard-won progress to date to enhance online privacy are in jeopardy by widespread online authentication requirements. It seems like any privacy lover should vigorously and publicly oppose those requirements.

1) AI. I see many parallels between AI Law circa 2023 and Internet Law circa 1995. We’re on the cusp of a technological revolution; everyone is arguing over analogies and metaphors to characterize the emergent technology; the academic literature is exploding; and regulators are gravitating towards myopic regulation (compare the 1996 CDA with, say, the EU AI Act).

1) AI. I see many parallels between AI Law circa 2023 and Internet Law circa 1995. We’re on the cusp of a technological revolution; everyone is arguing over analogies and metaphors to characterize the emergent technology; the academic literature is exploding; and regulators are gravitating towards myopic regulation (compare the 1996 CDA with, say, the EU AI Act).

Two big differences, however. First, the 1990s were an era of technological optimism which welcomed the Internet, while 2023 is an era of techlash where regulators are scared of AI. Second, there weren’t dominant Internet players in the mid-1990s aiming to protect their competitive position. In contrast, there are a few well-capitalized AI incumbents who would love to have regulators help them clean out their competition. These two differences create a fertile ground for disastrous regulation.

Thus, my feeling of deja vu is overwhelmed by an ominous sense of dread. In the 1990s, regulators fostered the Internet. Now, they aim to crush AI, and they may succeed.

Other noteworthy items.

- 9th Circuit’s YYGM ruling on contributory TM infringement. It’s probably impossible to define “willful blindness” without bumping into other scienter categories.

- Battles over politician-operated social media accounts. A tricky issue pending with the Supreme Court.

- The CCB celebrated its first birthday. Does anyone care?

- Constitutional challenge to AB587 fails. Twitter challenged the law without support from other industry players. The court couldn’t have been less interested. This challenge may be turbocharged, or shut down, by the Supreme Court’s decisions regarding the explanations requirements in the Florida and Texas social media censorship laws.

- TikTok bans. Techlash + Sinophobia = unconstitutional censorship.

Previous year-in-review lists from 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, and 2006. John Ottaviani and I previously listed the top Internet IP cases for 2005, 2004 and 2003.

* * *

My publications this year:

A SAD Scheme of Abusive Intellectual Property Litigation, 123 Columbia L. Rev. Forum 183 (2023)

Zauderer and Compelled Editorial Transparency, 108 Iowa L. Rev. Online 80 (2023)

How Santa Clara Law’s “Tech Edge JD” Program Improves the School’s Admissions Yield, Diversity, & Employment Outcomes, 27 Marq. IP & Innovation L. Rev. 21 (2023) (with Laura Lee Norris)

Internet Law: Cases & Materials (2023 edition)

Assuming Good Faith Online, Journal of Online Trust & Safety (forthcoming 2024)

The United States’ Approach to “Platform” Regulation (forthcoming)

Common Carriage and Capitalism’s Invisible Hand, Marquette Lawyer, Summer 2023, at 25 (critiquing James Speta, Can Common Carrier Principles Control Internet Platform Dominance?)

California’s Age-Appropriate Design Code Act Threatens the Foundational Principle of the Internet, Reason policy brief, September 7, 2023 (with Adrian Moore)

Advocacy Work

Moody v. NetChoice and NetChoice v. Paxton, amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of NetChoice and CCIA, December 2023 (with Michael Kwun)

Liapes v. Facebook, Amicus Curiae Letter to the California Supreme Court in Support of Petition for Review, November 2023 (with Horvitz & Levy)

Volokh v. James, amicus brief to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in support of the preliminary injunction, September 2023 (with TechFreedom)

Comments to the USPTO regarding Future Strategies in Anticounterfeiting and Antipiracy, Docket No. PTO-C-2023-0006, August 2023

Academics Letter to Congress regarding the Fourth Amendment Issues Posed by the EARN IT Act (S.1207, H.R.2732), May 2023

NetChoice LLC v. Bonta, amicus brief to the Northern District of California in support of a preliminary injunction, March 2023

Gonzalez v. Google LLC, amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of Google, January 2023

Pingback: Links for Week of January 19, 2024 – Cyberlaw Central()