When It Comes to Section 230, the Ninth Circuit is a Chaos Agent–Estate of Bride v. YOLO

The Ninth Circuit is interpreting Section 230 again. Time to grab your tissue box.

The Ninth Circuit is interpreting Section 230 again. Time to grab your tissue box.

* * *

The Jenga-ing of Section 230 continues in the Ninth Circuit. This time, the court blows up the Barnes precedent, which created a promissory estoppel bypass to Section 230, and says a claim based on pretty much any site disclosure can get around Section 230. By lowering what counts as a “promise” that 230 doesn’t apply to, the court has ensured that virtually every plaintiff can easily bypass Section 230 (they might still lose on the merits, but usually only after more costly litigation).

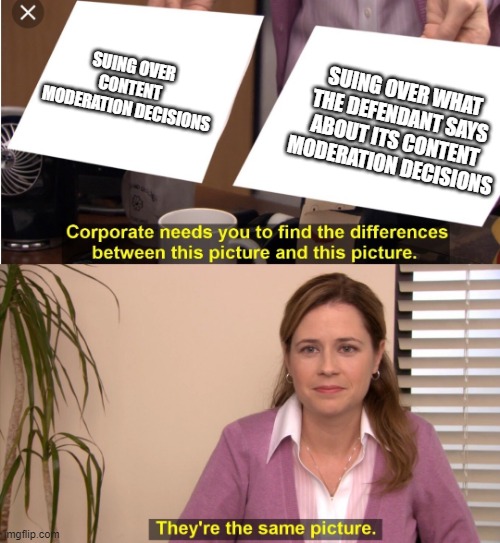

How so? Instead of suing the defendant on content moderation decisions, plaintiffs can sue on what the defendants said about their content moderation decisions. This will be trivially easy because plaintiffs can always find some site disclosure they think should have applied–as illustrated by this case, where the plaintiffs appear to be overinterpreting YOLO’s site disclosures. Thus, suing based on content moderation decisions versus what the site said about its content moderation decisions is a distinction without a difference–and that opens up the litigation floodgates.

EVEN WORSE…to reach this conclusion, the court had to:

- mangle the Barnes precedent by overassuming what “promises” satisfy its standards

- disregard part of the recent Calise v. Facebook case, where Section 230 preempted a promise-based false advertising claim

- disregard the California state courts, which have repeatedly held that Section 230 applies to contract breach claims

Other than that, this ruling was completely consistent with the precedent. 🙄

On the plus side, the court rejects the plaintiffs’ negligent design claims per Section 230, reiterating that the Lemmon v. Snap case isn’t a free pass around Section 230. This ruling has substantial implications for the social media addiction cases heading towards the Ninth Circuit.

[If you’re not a 230 nerd, you might stop reading here.]

* * *

Procedural Note

The opinion is written by Judge Siler, a senior 6th Circuit judge guest-sitting in the 9th Circuit. He was first appointed a federal judge in 1975 by President Ford. (according to Wikipedia, 6 Ford appointees are still on the bench in senior status). The panel was unanimous, but still, I wonder if this is the right person to be defining and trail-blazing 9th Circuit law? This might be one of several reasons why this case might benefit from en banc review. (Given the split results, it wouldn’t surprise me if both sides ask for en banc review).

Background

YOLO made an app for the Snapchat platform that “allows users to communicate anonymously, send polls and questions, and send and receive anonymous responses.” Knowing the risks of anonymous online engagements, “YOLO added two ‘statements’ to its application: a notification to new users promising that they would be ‘banned for any inappropriate usage,’ and another promising to unmask the identity of any user who ‘sen[t] harassing messages’ to others.” This is the opinion’s most precise statement of YOLO’s so-called “promises” to its users. The court didn’t provide verbatim quotes of the exact statements or any context around them.

The plaintiffs are bullying victims that claim YOLO didn’t do enough to protect them, even after they asked for help, and never could have protected them because it only had a staff of 10 to supervise a 10M user base. Snap suspended the YOLO app in 2021.

The lower court dismissed the case on Section 230 grounds. The appeals court divides the issues into “misrepresentation” claims, which Section 230 does not preempt, and “products liability” claims, which are preempted.

Publisher-Speaker Claims

Like Calise, the court treats the legal “duty” as the way to parse if the claim treats the defendant as a publisher/speaker of third-party content. “If it requires that YOLO moderate content to fulfill its duty, then § 230 immunity attaches.” However, “this does not mean immunity attaches anytime YOLO could respond to a legal duty by removing content…. moderation must be more than one option in YOLO’s menu of possible responses; it must be the only option.” This all sounds logical in a whiteboard sense, but I have no idea what it means or how to apply it. The court half-heartedly says there isn’t “a bright-line rule allowing contract claims and prohibiting tort claims that do not require moderating content” (yet another double-negative). That sounds like an invitation to other courts to do what they want and cite this language as an excuse.

Misrepresentation Claims

The court says:

YOLO’s representation to its users that it would unmask and ban abusive users is sufficiently analogous to Yahoo’s promise to remove an offensive profile. Plaintiffs seek to hold YOLO accountable for a promise or representation, and not for failure to take certain moderation actions. Specifically, Plaintiffs allege that YOLO represented to anyone who downloaded its app that it would not tolerate “objectionable content or abusive users” and would reveal the identities of anyone violating these terms. They further allege that all Plaintiffs relied on this statement when they elected to use YOLO’s app, but that YOLO never took any action, even when directly requested to by A.K

I have so many problems with this.

- What exactly were the “representations”? The court never provided them in full.

- Was YOLO’s representation an actual commitment? In other words, did reasonable consumers interpret it as a promise to unmask and ban every abusive user? What evidence does the court have that a reasonable consumer would have believed YOLO was guaranteeing those outcomes?

- Did YOLO even make a “representation” at all? Or was it content submission guidelines coupled with a scary-sounding remedy to encourage compliance?

- The court says obliquely that “it is certainly an open question whether YOLO has any defenses to enforcement of its promise.” Hold up–the plaintiffs have to establish the prima facie elements before we get to any defenses. I am highly skeptical that they can, and the court can’t ease the plaintiff’s burdens before shifting to defenses.

- The promise made in Barnes was personal to the plaintiff. It was an individual response to an individual removal request. That’s why promissory estoppel was plausible in Barnes’ case and isn’t plausible with respect to standard website disclosures. The court says that YOLO’s disclosures were “sufficiently analogous” to Yahoo’s promises to Barnes, but that seems like it needs more explanation. Or perhaps the court is suggesting that every website disclosure could be the basis of promissory estoppel claims…?

- The Calise case said “The predicate duty [under the state unfair competition law] is to not engage in unfair competition by advertising illegal conduct. Such a duty not only touches on quintessential publishing conduct, but it is also indeed the very conduct that § 230(c)(1) addresses.” As I wrote then, “How can the contract promise-based ‘duty’ be excluded from Section 230 but a false advertising-based ‘duty’–also a promise-based duty–be ‘the very conduct that § 230(c)(1) addresses???'”

- Several California state courts have held that Section 230 applies to contract-based claims that describe possible content moderation responsibilities. For example, in the Lady Freethinker case, the CA appeals court said: “Google’s actions allowing the animal abuse videos to be shown on YouTube thus fall squarely within the scope of a publisher’s traditional editorial functions—deciding whether to publish, withdraw, postpone or alter content….Google’s actions in allowing the animal abuse videos to be shown and failing to remove them amount to publishing decisions not to prevent or remove the videos…numerous courts have recognized the limited scope of [the Barnes] holding on this issue and have rejected attempts to evade section 230 liability by asserting distinguishable contract-based causes of action.” The 9th Circuit ignored the California state court rulings completely. This reinforces a growing divergence between California federal vs. state courts about the interplay between Section 230 and promise-based claims.

So where does this discussion leave services who hope to rely on Section 230? One way of reading the court’s opinion is that if the claim is based on website disclosures, it automatically gets around Section 230 (despite the court’s weak disclaimer against this result). Plaintiffs can frame the claim as contract breach, promissory estoppel, or false advertising and get a free pass.

The services’ countermove could be to clean up its language sufficient that no consumer could rely on it. This isn’t a practical option because (a) promise-like language lives in many places, and (b) tendentious plaintiffs can always find some way to read the language in a decontextualized and not-credible way.

Indeed, I’m sure that looking at YOLO’s supposed “representations,” there’s no way to reach the conclusions the plaintiffs are arguing–especially if viewed in the entire context. For this reason, the plaintiffs in this case aren’t likely to win on remand–and as other plaintiffs contort their interpretations of site disclosures to reach implausible interpretations, those will fail too. This seems destined to be yet another situation where a 230 exception creates another doctrinal dead-end (see the roster of 9th Circuit exceptions below), but everyone bears higher litigation costs to reach that outcome.

Worse, if further proceedings show that YOLO never made a legally actionable “misrepresentation,” then Section 230 should have applied now. That would be basically a redux of the Roommates.com case, where 8 years after the lawsuit was brought (and 4 years after the court said Section 230 apply to aspects of the claims), the Ninth Circuit held there never was a legal violation in the first place and Roommates.com always deserved to win its Section 230 defense. The Ninth Circuit appears to be making this same error again, having learned nothing from its Roommates.com debacle.

Even worse, the Roommates.com exceptions to Section 230 proved to be fairly minor in practice, but an exception for claims based on any site disclosures is a bonanza for every plaintiff’s lawyer because they can always find something on the defendant’s website to get around Section 230. (At this point, if a plaintiff’s lawyer can’t figure out how to survive a Section 230 motion to dismiss in the Ninth Circuit, they should hand in their bar card). So this ruling will cause much more damage than the Roommates.com ruling did.

Perhaps recognizing that it was blowing up Section 230 and the Barnes precedent, the court concluded:

In holding that the Plaintiffs’ misrepresentation claims may proceed, we adhere to long-established circuit precedent. We must strike a delicate balance by giving effect to the intent of Congress as expressed in the statute while not expanding the statute beyond the legislature’s expressed intent in the face of quickly advancing technology. Today’s decision does not expand liability for internet companies or make all violations of their own terms of service into actionable claims. To the degree that such liability exists, it already existed under Barnes and Calise, and nothing we do here extends that legal exposure to new arenas. Section 230 prohibits holding companies responsible for moderating or failing to moderate content. It does not immunize them from breaking their promises. Even if those promises regard content moderation, the promise itself is actionable separate from the moderation action, and that has been true at least since Barnes. In our caution to ensure § 230 is given its fullest effect, we must resist the corollary urge to extend immunity beyond the parameters established by Congress and thereby create a free-wheeling immunity for tech companies that is not enjoyed by other players in the economy.

The last line brought to mind this GIF:

It’s like the court thinks Internet companies are enjoying a no-fucks-given joyride, with Section 230 as their sweet wheels. The truth is completely opposite of that. Section 230 is the tool that empowers users to talk with each other online, and services are clinging onto that protection (increasingly vainly) to enable those conversations. Also, the court’s anti-exceptionalism attitude is misdirected. There are many good reasons why Congress favored Internet services over other industries. Maybe the court would like to consult the extensive literature on that very question?

Overall, this concluding paragraph felt defensive, like the court was trying to gaslight readers into thinking that this opinion doesn’t change anything when it’s changing a lot.

Product Liability Claims

The plaintiffs claimed “YOLO’s app is inherently dangerous because of its anonymous nature, and that previous high-profile suicides and the history of cyberbullying should have put YOLO on notice that its product was unduly dangerous to teenagers.” The court responds:

all Plaintiffs’ product liability theories attempt to hold YOLO responsible for users’ speech or YOLO’s decision to publish it. For example, the negligent design claim faults YOLO for creating an app with an “unreasonable risk of harm.” What is that harm but the harassing and bullying posts of others? Similarly, the failure to warn claim faults YOLO for not mitigating, in some way, the harmful effects of the harassing and bullying content. This is essentially faulting YOLO for not moderating content in some way, whether through deletion, change, or suppression.

This gives the court an opportunity to clarify Lemmon v. Snap:

Plaintiffs allege that anonymity itself creates an unreasonable risk of harm. But we refuse to endorse a theory that would classify anonymity as a per se inherently unreasonable risk to sustain a theory of product liability. First, unlike in Lemmon, where the dangerous activity the alleged defective design incentivized was the dangerous behavior of speeding, here, the activity encouraged is the sharing of messages between users. Second, anonymity is not only a cornerstone of much internet speech, but it is also easily achieved. After all, verification of a user’s information through government-issued ID is rare on the internet. Thus we cannot say that this feature was uniquely or unreasonably dangerous.

As the court reiterates, Lemmon v. Snap doesn’t help plaintiffs when the claim is based on “the sharing of messages between users.” However, the court’s fact claim that online authentication is “rare” is dicey. Governments are requiring authentication broadly, including California’s Age-Appropriate Design Code that the 9th Circuit just addressed without addressing the age authentication requirement. Authentication requirements will remain rare only if the courts continue to strike down the multitudinous authentication requirements that governments seek to impose.

The court also distinguishes the Internet Brands case, saying that “the defendant in Internet Brands failed to warn of a known conspiracy operating independent of the site’s publishing function.” (I guess that’s one way to put it. Internet Brand’s only role in the equation was publishing messages between criminals and victims). The court sees it differently here:

here, there was no conspiracy to harm that could be defined with any specificity. It was merely a general possibility of harm resulting from use of the YOLO app, and which largely exists anywhere on the internet. We cannot hold YOLO responsible for the unfortunate realities of human nature.

That last sentence is powerful, and one I expect defendants to cite extensively. The court essentially adopts the “Internet as a mirror of society” theory.

The court also “clarifies” the Dyroff opinion. Normally, “clarification” announces the overturning of precedent, but the court says the rejection of product liability claims here is consistent with Dyroff despite some fact differences:

the communications between users were direct, rather than suggested by an algorithm, and YOLO similarly provided users with a blank text box. These facts fall within Dyroff’s ambit.

The court summarizes:

Those product liability claims that fault YOLO for not moderating content are foreclosed; otherwise, nothing about YOLO’s app was so inherently dangerous that we can justify these claims, and unlike Lemmon, YOLO did not turn a blind eye to the popular belief that there existed in-app features that could only be accessible through bad behavior. And to the degree that the online environment encouraged and enabled such behavior, that is not unique to YOLO. It is a problem which besets the entire internet.

The court doesn’t expressly address the social media addiction cases, but this is not a good ruling for those plaintiffs. The defendants will surely point out the rejection of the negligent design claims–a central piece of the addiction lawsuits–and all of the “features” at issue involve the republication of third-party content. i.e., what’s being autoscrolled? Third-party content. What are users “addicted” to? Third-party content. The addiction plaintiffs can still respond that they are suing over the “design choices” per Lemmon v. Snap, but the limiting language about Lemmon makes that argument a little harder. At minimum, this opinion should end the obviously preempted claims where the plaintiffs are just pretextually citing negligent design to impose liability for third-party content (exactly as the YOLO plaintiffs tried).

Case Citation: Estate of Carson Bride v. YOLO Technologies, Inc., 2024 WL 3894341 (9th Cir. Aug. 22, 2024)

Also of note: The FTC recently settled with a sketchy app, NGL, similar to YOLO. This opinion rejects a number of the premises that the FTC relied on, reinforcing the likely lawlessness of the FTC’s enforcement action.

Keeping Track of the Ninth Circuit’s Section 230 Common Law Exceptions

A list of the ever-growing Section 230 exceptions in the Ninth Circuit:

- Batzel v. Smith: exclusion for third-party content not intended for publication

- Roommates.com: exclusions for (1) encouraging illegal content, (2) requiring the input of illegal content, and (3) materially contributing to content illegality. Recall the tortured history of that case: the initial panel decision prompted en banc review and a new en banc opinion, which was later rendered dicta by further proceedings.

- Barnes v. Yahoo: exclusion for promissory estoppel (expanded in this case to all contract claims). The panel had to amend its initial opinion.

- Doe v. Internet Brands and Beckman v. Match.com: exclusion for failure-to-warn. The panel had to completely replace its initial Internet Brands opinion.

- HomeAway v. Santa Monica: exclusion for consummating third-party transactions.

- Enigma v. Malwarebytes: exclusion when the plaintiffs allege “anti-competitive animus.” This case went back to the Ninth Circuit.

- Gonzalez v. Google: exclusion for funding third-party content. I’m not sure what’s left of this exclusion after the Supreme Court ruling.

- Lemmon v. Snap: exclusion for “negligent design” (when not based on third-party content).

- Vargas v. Facebook: exclusion for discriminatory ad targeting. Non-precedential opinion.

- Quinteros v. Innogames: exclusion for moderators’ activities. Non-precedential opinion.

- Diep v. Apple: exclusion for first-party marketing representations. Non-precedential opinion.

- Calise v. Facebook: exclusion for contract-based claims.

- Bride v. YOLO: exclusion for all first-party disclosures, even if they aren’t part of a contract.

The last four are from 2024 (and it’s only August). The pace of Section 230’s demise is quickening…. 📉

Pingback: Bonkers Opinion Repeals Section 230 In the Third Circuit-Anderson v. TikTok - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()