Another Confused Entry in the Social Media Account Ownership Jurisprudence–JLM v. Gutman

This is a lawsuit between a wedding gown company, JLM, and Hayley Paige Gutman, a designer/influencer who worked for JLM. For background, check out my post on the district court’s ruling here: “Social Media Ownership Disputes Part II: Bridal Wear Company Takes Back Control of Instagram Account from Ex-Employee”.

Gutman signed an employment agreement with JLM. It did not specifically address ownership of social media accounts. It contained a non-compete clause that said Gutman wouldn’t compete directly or indirectly with JLM during her employment. The agreement also granted a license to JLM in Gutman’s name (“Hayley, Paige, Hayley Paige Gutman, Hayley Gutman, Hayley Page, or any derivative thereof”). Gutman gave JLM the “exclusive” right to use her name in connection with bridal wear for the term of the agreement and two years following (provided she participated in the design of such clothing). She also granted JLM rights in the trademarks relating to her name.

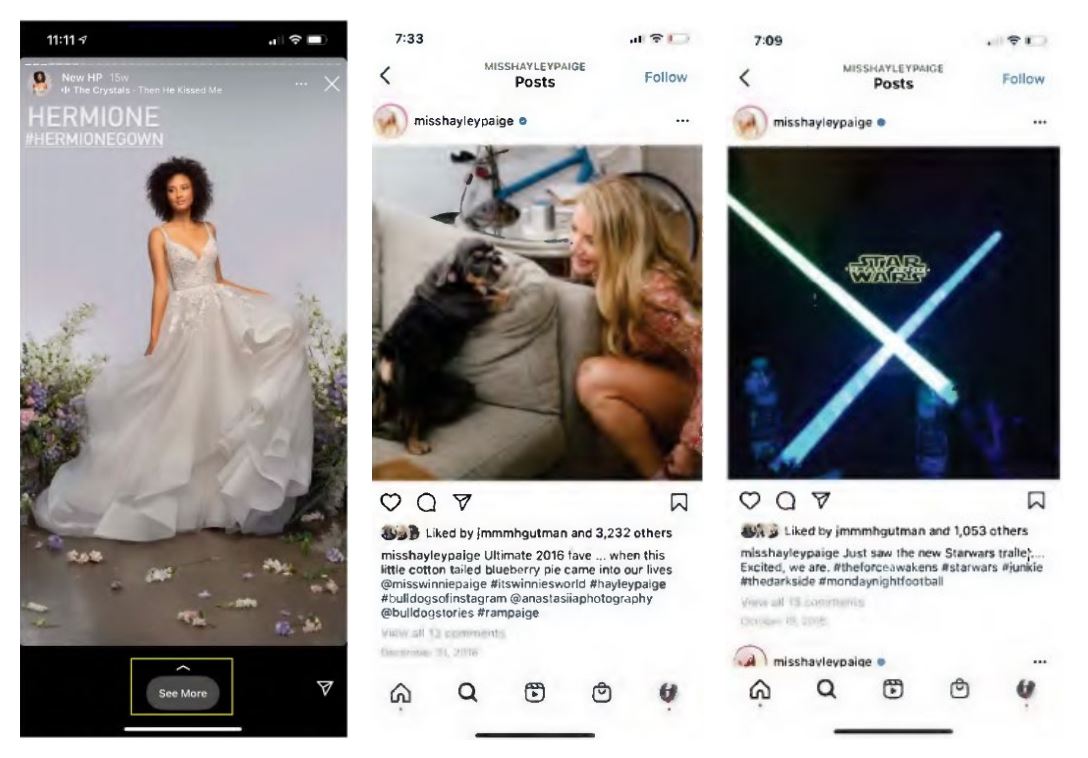

Gutman operated several Hayley Paige-themed accounts before her employment (on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn) and five accounts during her employment with JLM (on Pinterest, Instagram, Snapchat, Spotify, and TikTok). The Instagram account contained a blend of personal and professional posts. The posts promoted JLM’s “Hayley Paige brand,” but also included photos of Gutman with her dog and her “reflections on a recently released Star Wars movie trailer.” Gutman largely operated the account, but another JLM employee also had responsibility for “managing” it. On occasion, JLM’s CEO gave input on what Gutman should post.

During the first several years of Gutman’s employment, the parties had a productive relationship. Sales of apparel she designed were substantial, and her profile grew as well. At some point, the parties discussed revisiting the contract terms; these discussions ended up blowing up the relationship. According to court filings, Gutman changed the @misshayleypaige Instagram account’s password (to lock out JLM) and changed the bio to reflect it was a personal account. She also created a “misshayleypaige” account on TikTok. Finally, she promoted third party products from the Instagram account without JLM’s permission. She also promoted her upcoming appearance at a bridal expo that referenced her personally and not JLM.

In late 2020, JLM sued, asserting, among other claims, that Gutman: (1) violated her non-compete by agreeing to appear at the bridal expo; (2) breached the name-rights agreement by using the “misshayleypage” Instagram account for third-party promotions; and (3) converted the Instagram, TikTok, and Pinterest accounts by refusing to cede control of them (and by locking JLM out of the Instagram account).

The court says the three accounts JLM claimed ownership over (Instagram, TikTok, and Pinterest), “especially the Instagram account, are valuable assets.” One expert opined that “a single post on the [Instagram] account is worth nearly $30,000.” The Instagram account receives the most attention from the parties and the court.

The district court granted an injunction that gave control over these key social media accounts to JLM during the pendency of the litigation. The Second Circuit opinion reviews the district court’s grant of injunctive relief. While it affirms the district court’s order, it remands with respect to the issue of who gets to control the social media accounts while the litigation is pending.

Noncompete Agreement: The court says preventing Gutman from competing with JLM during the term of the agreement was appropriate. The district court found that Gutman likely breached the agreement by ceasing to provide her services to JLM. While the district court did not force her to continue to work for JLM, the Second Circuit said the district court acted within its discretion in deciding that Gutman nevertheless could not compete with JLM. The court finds that the non-compete is enforceable under New York law, and given the unique nature of Gutman’s services, injunctive relief was reasonable and appropriate.

Name Rights: The court also ruled for JLM on the name rights issue. The agreement precludes Gutman from using the “Designer’s Name” (the defined term) commercially during the term. She argued that the language should be read to interpret “Designer’s Name” in the trademark sense (as limited by the rights JLM may have in the trademarks). The court says a catch-all provision in the name-rights section references “other names and marks,” so the Designer’s Name is intended to be distinct from the trademarks. The Second Circuit says the district court was correct in barring Gutman from using various iterations of her name “in trade or commerce” while the litigation was pending.

Social Media Accounts: The appeals court observes that the district court did not grapple with the merits of JLM’s conversion and trespass to chattels claims but nevertheless granted an injunction that essentially transferred ownership over the accounts to JLM. This was erroneous. The court notes the parties have divergent views on (1) when the accounts were created and whether they were personal or professional (or a mix), and (2) who had authority to post on the accounts. The court concludes that Gutman’s alleged contract breaches are not a sufficient basis to give total control of the account to JLM:

[the] contractual breaches identified by the district court do not correspond to the injunctive relief JLM sought, which was clearly structured to remedy JLM’s conversion and trespass claims.

The court is troubled by the fact that, during the pendency of the injunction, Gutman would be barred from posting content in a manner that violates her agreement with JLM and can’t even post personal content to the accounts. The injunction is thus overly broad:

The overbreadth of this part of the PI reflects the fact that the character of the district court’s relief—a grant of perpetual, unrestricted, and exclusive control throughout the litigation—sounds in property, not contract.

The court acknowledges Judge Lynch’s suggestion in his concurring and dissenting opinion of a possible slimmed-down version of the injunction (that perhaps envisions joint control over the account(s)). However, according to the panel opinion, even this does not do an adequate job of correlating the relief awarded to JLM to the breaches in question.

Judge Newman’s Dissent: Judge Newman dissented on the basis that prohibiting Gutman from using her own name is an “extraordinary step” that should not be taken lightly. He would find there is conflicting language in the agreement on the issue of whether Gutman signed away–without limitation–her ability to use her own name. One of the provisions of the agreement only envisioned that JLM had the right to use Gutman’s name in connection with apparel Gutman had a hand in designing or creating. In Judge Newman’s view, this more restrictive provision, along with the trademark-related terms, should be the anchor of the court’s analysis regarding name rights.

Judge Lynch’s Concurrence/Dissent: Judge Lynch concurred in the panel’s ruling on the non-compete and name restriction issues. However, he would have affirmed the district court’s opinion at least as to the Instagram account (the one the parties focused on). Judge Lynch found that the injunction only required Gutman to give JLM access to the account and prevented Gutman from posting unapproved content to the account (or generally altering content previously posted to the account). Unlike the majority, Judge Lynch doesn’t see this as tantamount to ownership of the account. Instead, this relief can be premised on JLM’s license to use Gutman’s name, and the fact that the account was a work-related account. The account was started after employment and bears a name that was licensed to JLM. The account was used to promote JLM’s business and JLM in fact exerted influence over what was posted to the account. In Judge Lynch’s view, the injunction just restores the parties to where they were before Gutman’s breach. Finally, in a footnote, he notes that he doesn’t want to speculate about the possibility that the injunction can be modified to provide for “joint management and control” of the Instagram account.

___

This may be the first appeals court ruling to confront the nature of ownership over a social media account. (Our first post on this topic, blogging the dispute over the @OMGFacts Twitter account, was over ten years ago!) Unfortunately, like many of the other cases in this genre, the court’s opinion does not provide a definitive take. The court focuses on the agreement between JLM and Gutman, but in the end, is the agreement between Instagram and Gutman equally important to answering the question of whether JLM is likely to succeed on its conversion or trespass to chattels claims? The property-vs-contract vibe from the panel ruling reminds me of domain name / collections cases. Perhaps it’s easy to say that spelling out ownership of social media accounts in the parties’ relationship is key, but I’m not sure that would have yielded an easy result with this panel. (The agreement was filed under seal in the district court.)

Eric recently posted about the By Chloe case, another license/sale of name rights that exploded into litigation. Another parallel with this case: the Chloe case also involved a millennial woman who sold name rights to a corporation.

We’ve blogged about state laws directed at ownership of (and privacy regarding) employee social media accounts. It’s doubtful those would have been helpful in this instance. One issue with these laws is that social media accounts often evolve and involve a mix of personal and professional. This makes it a challenge to define them. This theme came up in the Trump twitter account case that was also in front of the Second Circuit. For Eric’s critique of those laws generally, see this post: “The Spectacular Failure of Employee Social Media Privacy Laws“.

The dispute is raging on in the district court. Unfortunately, the pleadings haven’t been finalized, and although there have been motions to dismiss filed, the district court hasn’t issued a ruling (beyond what it said in the TRO and injunction orders) regarding the viability of JLM’s conversion and trespass to chattels claims. It’s amazing to see how heavily this case has been litigated, and the amount of money that must have been spent.

The “joint control” over the account during the pendency of the litigation concept sounds like a nightmare.

JLM posted a bond ($200K) in the district court. The district court can revisit in the first instance whether it should have granted injunctive relief to JLM, but if it decides JLM is not entitled to the accounts during the pendency of the litigation, it will be interesting to see the parties’ arguments regarding disposition of the bond amount.

I’m not sure what to make of this correspondence Judge Swain received, but in combing the docket I came across it. So I’m sharing.

Other coverage: Marty Schwimmer; Fashion Law

Case citation: JLM Couture, Inc. v. Gutman, 2022 WL 211017 (2d Cir. Jan. 25, 2022)

Related Posts:

Ex-Employee’s Continued Use of Twitter Account May Be Conversion–Farm Journal v. Johnson

The Spectacular Failure of Employee Social Media Privacy Laws

Do Employers Own LinkedIn Groups Created By Employees?–CDM v. Sims

Creating Parody Social Media Accounts Doesn’t Violate Computer Fraud & Abuse Act – Matot v. CH

When Does A Parody Twitter Account Constitute Criminal Identity Theft?–Sims v. Monaghan

Trademark Owner Sues Over Alleged Twittersquatting–Coventry First, LLC v. Does

Steps Brand Owners Can Take to Deal With Brandjacking on Social Networks

Battle Over LinkedIn Account Between Employer and Employee Largely Gutted–Eagle v. Morgan

Ex-Employer’s Hijacking of a LinkedIn Account Is a Publicity Rights Violation–Eagle v. Morgan

“Social Media and Trademark Law” Talk Notes

Court Denies Kravitz’s Motion to Dismiss PhoneDog’s Amended Claims — PhoneDog v. Kravitz

An Update on PhoneDog v. Kravitz, the Employee Twitter Account Case

Another Set of Parties Duel Over Social Media Contacts — Eagle v. Sawabeh

Court Declines to Dismiss or Transfer Lawsuit Over @OMGFacts Twitter Account — Deck v. Spartz, Inc.

MySpace Profile and Friends List May Be Trade Secrets (?)–Christou v. Beatport