Police Officer’s Facebook Post Criticizing Her Boss Isn’t Protected Speech–Graziosi v. Greenville

Graziosi was a Sergeant of the Greenville Police Department. She alleges she was wrongfully discharged due to comments she posted to Facebook. She posted the following to her page and to the “Elect Chuck Jordan Mayor” page:

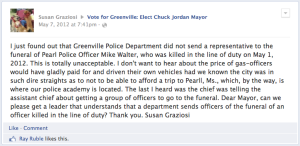

I just found out that Greenville Police Department did not send a representative to the funeral of Pearl Police Officer Mike Walter, who was killed in the line of duty on May 1, 2012. This is totally unacceptable. I don’t want to hear about the price of gas–officers would have gladly paid for and driven their own vehicles had we known the city was in such dire straights (sic) as to not to be able to afford a trip to Pearl, Ms., which, by the way, is where our police academy is located. The last I heard was the chief was telling the assistant chief about getting a group of officers to go to the funeral. Dear Mayor, can we please get a leader that understands that a department sends officers of (sic) the funeral of an officer killed in the line of duty? Thank you. Susan Graziosi

Then in response to comments, she said “I’m mad. (can you tell).” In a more detailed follow-up comment fourteen hours later, she continued:

…we had somethings (sic) then that we no longer have….LEADERS. I don’t know that trying for 28 is worth it. In fact, I am amazed every time I walk into the door. The thing is the chief was discussing sending officers on Wednesday (after he suspended me but before the meeting was over). If he suddenly decided we “couldn’t afford the gas” (how absurd – I would be embarrassed as a chief to make that statement) he should have let us know so we could have gone ourselves. Also, you’ll be happy to know that I will no longer use restraint when voicing my opinion on things. Ha!

Later on May 7, 2012, Ms. Graziosi made an additional post which stated “If you don’t want to lead, can you just get the hell out of the way” and then commented on her own post “seriously, if you don’t want to lead, just go.”

She was terminated for violation of Greenville Police Department rules of conduct 2.14, 3.2 (supporting fellow employees); 3.8 (chronic complaining); and 3.7 (an act of disobedience).

Her speech was not a matter of public concern: Since Graziosi is a public employee, she has to show that her speech was a matter of public concern and that her interest in the speech outweighs the government employer’s interest in workplace efficiency. The court focuses on the first element and says that the key distinction is whether she was speaking as a citizen or as an employee. The court concludes her posts were more relevant to “her own frustration” and were not intended to expose any wrongdoing or unlawful conduct. She argued that the public is obviously interested in how public funds are spent or not spent, but the court says this looks at the speech too broadly. At this level of abstraction, the court says anything is a matter of public concern. The court also notes that she uses words such as “we” or “our” which denote that she’s voicing an employee, rather than a public, concern.

The police department’s interest in efficiency justified the firing: Although the court concludes that the speech is not a matter of public concern, the court says that even if it was, the Chief could properly fire her. The post generally raised “buzz” in the office and caused a change in demeanor of other officers towards the Chief. One of the officers testified that he initially posted a comment to Graziosi’s post but then clarified it after learning that someone in the office was upset by his comment. The court says that while it would be different if the original post talked about illegal or even unethical conduct, disruption caused by something less can be proper grounds for termination.

__

Two interesting footnotes to the court’s order. First, the court rejects Facebook’s “self serving” assertion from its amicus brief in Bland v. Roberts that it enables “rich” communication (fn 1). This is somewhat out of the blue, since Facebook did not file a brief in (and is not a party to) this case. Second, the court notes its awareness that “Facebook, Twitter, and the like seem to have a ‘special’ power to bring an issue before the masses, especially when a story goes viral…” (fn. 8).

This is a tough case. Bland v. Roberts, the Facebook firing case that raised the question of whether a Facebook “like” was protected speech, was somewhat easier because the question in that case was whether the “like” gesture which was a factor in the firing was speech at all. The trial court said no, but the Fourth Circuit reversed. Here there’s obviously expression, but the question is whether it’s a matter of public concern. The distinction used by the court as to whether she was speaking as an employee or a member of the public seemed somewhat arbitrary, and the key question is whether it’s speech that involves a matter of governance. In posting the statement to the “Elect Chuck Jordan” page [he’s now deceased, incidentally], she signals this, but the court does not give it any credence. I’m on the fence, and I admit the public would be more obviously interested if the post raised the issue of funds being wrongly spent. Still, Eric makes a good point below about the expenditure of funds always being something the public is interested in.

Public employers have wide leeway to fire employees in these circumstances, and the employer does not have to show much to make the case that the speech was “disruptive” or “interfered with efficiency”. That probably goes double when you are talking about a police department. It’s worth noting that a propriety of the firing based on the comment and the propriety of the department’s policy could very well go the other way if we were dealing with a private employer and the NLRB’s position. (See “Overreactive Guidance for Social Networking Du Jour — NLRB Edition“.) If a BMW salesman’s post complaining about the quality of food at a sales event is not a proper cause for firing, it’s easy to see how firing someone for complaining about not supporting fellow officers by attending a funeral is likewise improper. Many aspects of the police department’s policy also are on par with employee handbook “courtesy” and “decorum” rules that the NLRB has frowned on. A strange quirk I’ve noted before under the NLRB and public employee speech rules is that when it comes to terminating employees for speech, the law may impose greater restrictions on private employers than public ones.

An interesting companion to Bland v. Roberts. It would be great to see these issues in this case hashed out on appeal.

Eric’s Comments: Based on the court’s recitation of facts, Graziosi got a tough break. To me, budget decisions by police departments, and the effectiveness of the police department’s leadership, are always matters of substantial public interest. The fact that the conversation partially took place on a mayoral candidate’s page only seems to reinforce this point–especially if the mayor appoints the police chief and therefore has supervisory responsibility for the position. (If the police chief position is elected, then that would make it even more clear this was a matter of public concern). And while I’m sure that Graziosi’s remarks caused division in the department, that’s the natural result of controversial remarks on locally important topics. I’m not sure if Graziosi will appeal the ruling, but like the initial Bland v. Roberts ruling, this seems like a ruling that would benefit from appellate review.

I’ve been working on my list of top 10 Internet Law developments of 2013, and the firing of government employees for their Facebook posts will surely make the list. I don’t think Graziosi’s remarks were as ill-advised as some of the others we’ve seen (like Tyson Lynch or Jennifer Shepherd), but at this point, I think the lesson for public employees is clear: Facebook and other social media is a dangerous place to discuss work-related matters. Stick to kvetching about your job around the water cooler or over beers at the local watering hole, just like the good old days.

Case citation: Graziosi v. City of Greenville, 4:12-CV-68-MPM-DAS, 2013 WL 6334011 (N.D. Miss. Dec. 3, 2013).

Other coverage: “Facebook Posts by Police Officer Not Protected by the 1st Amendment” (“Another win for employers in the workplace battle involving social media”) (Molly DiBi)

Related Posts:

* Facebook Complaints About Boss’s Creepy Hands Can’t Salvage Retaliation/Harassment Claims

* Facebook Rant Against ‘Arial’ Font Helps Reverse Sex Offender Determination

* Social Worker’s Facebook Rant Justified Termination — Shepherd v. McGee

* The First Amendment Protects Facebook “Likes” – Bland v. Roberts

* Facebook “Likes” Aren’t Speech Protected By the First Amendment–Bland v. Roberts

* Employee Wins Harassment Claim Based in Part on Co-Workers’ Offsite Blog Posts

* Overreactive Guidance for Social Networking Du Jour — NLRB Edition

* Private Employers and Employee Facebook Gaffes [Revisited] and the prior post Do Employers Really Tread a Minefield When Firing Employees for Facebook Gaffes?

* Employee Terminated for Facebook Message Fails to State Public Policy Claim — Barnett v. Aultman

* Employee Wins Harassment Claim Based in Part on Co-Workers’ Offsite Blog Posts–Espinoza v. Orange

Pingback: AAUP Says Kansas Regents’ New Faculty Social Media Use Policy Violates Academic Freedom (Guest Blog Post) | Technology & Marketing Law Blog()

Pingback: Top Ten Internet Law Developments Of 2013 (Forbes Cross-Post) | Technology & Marketing Law Blog()

Pingback: 9th Circuit Issues a Blogger-Friendly First Amendment Opinion–Obsidian Finance v. Cox | Technology & Marketing Law Blog()

Pingback: In Mississippi tax breaks and the gang at Port and Harbor in the news | Slabbed()

Pingback: Facebook Post Isn’t Good Reason To Remove Attorney From Probate Court Case Assignment List | Technology & Marketing Law Blog()