Organizing an “Internet Safety” Presentation? Don’t Troll Through Students’ Facebook Accounts Looking for Bikini Photos

[By Venkat Balasubramani, with comments from Eric]

Chaney v. Fayette County Public School Dist., 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 143030 (N.D. Ga. Sept. 30, 2013).

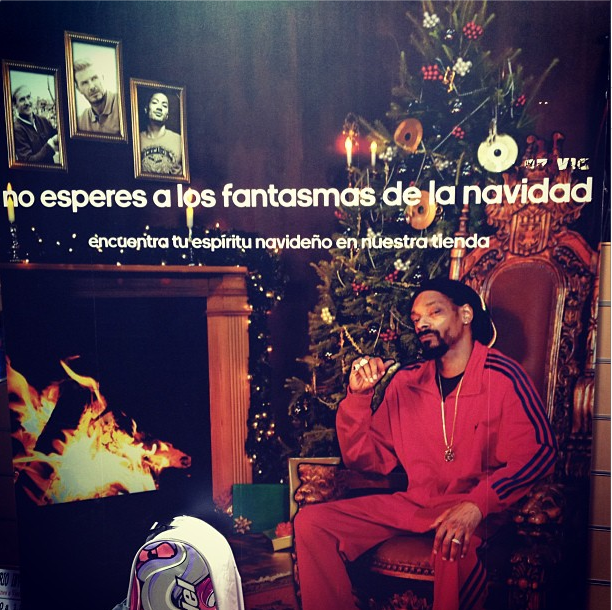

Chelsea Chaney posted a photo to Facebook of herself in a bikini standing next to a life-size cutout of Calvin “Snoop Lion” Broadus (f/k/a Snoop Dogg). [With some reluctance, we’re sharing a link to a page where you can find the photo.] Chelsea’s Facebook privacy settings made the photo available to both to her “friends” and “friends of friends”. Curtis Cearley, the director of IT services for the Fayette County public school district in Fayetteville, put together a presentation on “internet safety”.  One slide featured a cartoon of a daughter approaching her mother about the mother’s Facebook page “from years past”. The page included as the mother’s hobbies “body art, bad boys, and jello shooters”. The immediately following slide featured the picture of Chaney posing with the Snoop Lion cutout. Chaney was identified by name.

One slide featured a cartoon of a daughter approaching her mother about the mother’s Facebook page “from years past”. The page included as the mother’s hobbies “body art, bad boys, and jello shooters”. The immediately following slide featured the picture of Chaney posing with the Snoop Lion cutout. Chaney was identified by name.

Chaney sued the IT director and school district, among others, alleging that use of her photo was both an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment and a violation of her constitutional privacy right under the Fourteenth Amendment. She also asserted state law claims.

Fourth Amendment claim: Chaney’s Fourth Amendment claims stumbles because she didn’t have a legitimate expectation of privacy in the Facebook photo. She contended that the photos were only accessible to “people she had specifically approved,” but the court disagrees:

Chaney fails to acknowledge the lack of privacy afforded her by her selected Facebook setting. While Chaney may select her Facebook friends, she cannot select her Facebook friends’ friends. . . . Chaney not only voluntarily turned over the picture to her Facebook friends, but she also chose to share the picture with an additional audience of unknown size, likely comprised of people Chaney did not know, subject to continuous expansion without Chaney’s approval.

The court easily concludes that having “chose[n] to share [the photo] with the broadest audience available to her,” she surrendered any reasonable expectation of privacy in the photo. (citing US v. Meregildo)

The court says that the fact that the photo was a bikini photo does not change the result. While the result may have been different if there was some element of involuntariness in the photo, she voluntarily posed for and posted the photo, so she’s out of luck.

Fourteenth Amendment claim: Her Fourteenth Amendment-based privacy claim also fails. While this right has been found to encompass decision-making and confidentiality and non-disclosure, it doesn’t create “a constitutional right to be free from public embarrassment or damage to [a person’s] reputation.” The court analogized to an older Eleventh Circuit case where a photograph accidentally exposing a student’s penis was printed in a yearbook with a “lurid caption”. The constitutional privacy claim failed. The court says this case is even weaker:

Chaney intentionally shared a picture of herself in a bikini with a broad audience, and she had no control over how that audience might use her photo.

The District’s liability : Finally, the court also says that regardless of whether there was a constitutional violation, the district could not be held liable. To hold the district liable, Chaney would have to point to an express policy that violated her rights. The district had a policy that prohibited any employees from using internet or email “in a way that could cause offense to others or harass or harm them . . . or [could] in any other way be inappropriate for the school environment.” The court says that rather than expressly authorizing the conduct she complains of, the district policy actually prohibits it. Accordingly, she can’t make a claim for entity liability.

[Sidenote: the policy is on thin ice from a First Amendment standpoint. Although not directly on point, see Rodriguez v. Maricopa County Community College District. Also, the court mentions the district’s social media guidelines that require employees to notify a student’s parents before “any interaction with a student’s social media page”. Yeesh.]

__

Another case that addresses the venerable question of when something posted to social networks is “private” and whether third parties can access or use this information. This issue arose in one of Eric’s favorite cases (Moreno v. Hanford Sentinel) and several others since then. (Ehling v. Monmouth Ocean Hosp., the shoulder surfing case; US v. Meregildo, the case where the government accessed a defendant’s profile information through the target’s “friend”). Unfortunately for Chaney, as for every other person who has tried to make a similar argument, Facebook privacy settings do not result in a finding that the information posted to her account and viewable by “friends” was private. As Eric notes below, it can be difficult to effectively navigate through the labyrinth that is Facebook’s privacy controls, but courts are not particularly sympathetic to user privacy arguments based on the complexity of Facebook’s settings. Through this litigation, Chaney learned a lesson both about who could access her information and to what extent courts would protect her privacy in it. In the process, she generated some good fodder for future “internet safety” education campaigns.

This case also brings up two pieces of legislation that is a part of California’s wave of privacy legislation:

CA eraser law: Eric blogged about California’s eraser law for minors. Although Eric explains why it’s not a great law, it’s something she could have tried to take advantage of. This scenario illustrates why the statute would not necessarily have been much help to her—the content already has been accessed and disseminated by the IT administrators. Sure, she could prevent similar incidents in the future by having it removed from Facebook, but it’s of little use to her here.

Revenge porn law: This is obviously not revenge porn as such, but it’s worth considering the statute’s possible applicability here. It applies only to “private” photos and since Chaney posted them to Facebook, they would not come under the statute. The statute also only covers pictures taken by someone of the victim. One gaping hole in the statute is that it does not cover selfies, but it also doesn’t cover dissemination by a third party such as occurred here. (See “California’s New Anti-Revenge Porn Bill Won’t Protect Most Victims“; “California’s New Law Shows It’s Not Easy To Regulate Revenge Porn“.)

It’s worth noting that Cearley, the IT administrator, may not be totally off the hook. It’s possible that Chaney can bring some state law claims against him (e.g., for outrage or possibly negligence). Cearley has a possible First Amendment defense to any such claim, but the court did not take those claims or defenses off the table.

_____

Eric’s Comments

Another casualty of Facebook’s privacy settings. Even sophisticated Internet users don’t understand Facebook’s friend-of-a-friend setting (see, e.g., how Mark Zuckerberg’s sister Randi got tripped up by the friend-of-a-friend setting). If a Facebook user has 200 friends and each of them has 200 unique friends (i.e., no overlaps in friends), posting a photo with a friend-of-a-friend setting means a potential audience of 40,000 individuals. Facebook doesn’t calculate this number for users or encourage users to do this math, but it should. The results would shock most people and would surely do more to get users to think twice than another “Internet safety” training. If you haven’t checked your Facebook settings recently, here’s another friendly reminder to revisit who can see your content–either make your Facebook feed open to the world and proceed accordingly, or limit your posts to your friends and pray that they don’t betray your trust. I limit my Facebook feed to my friends, but everything I post to Facebook is also on Twitter/LinkedIn/Google+ with the understanding that none of it is private.

Once we realize that Chaney made her bikini photo available to thousands of other Facebook users, it’s not credible for her to argue that it was “private” as a legal matter. But assuming she made the broad publication “choice” unintentionally, what are we going to do about this? I don’t think legal rules can meaningfully keep digital content from leaking out of easily breached digital containers.

It’s also tempting to criticize Cearley for trolling around Facebook looking for bikini photos of his students. In theory, Cearley could have made his point with a photo from a student outside the district. However, the fact that he put Chaney on the big screen, and not some random stranger, makes a huge difference to Cearley’s audience. The risk of digital content leakage becomes much more salient to the students when they realize that Cearley could have just as easily picked one of their photos. I probably wouldn’t have advised Cearley to take the steps he did, but given the important message conveyed through his choices, the First Amendment should protect those choices.

Other coverage:

Justin Webb: “Court dismisses most of teen’s suit for use of bikini-clad photo from Facebook in high school “Internet Safety” class”

Molly DiBianca: “No Privacy Claim for Use of Student Facebook Picture”

Related posts:

“Cynthia Moreno Guest Lecture to My Internet Law Course”

“My Talk to High Schoolers About Accountability for Online Content“