Gambling App Fails to Create Binding Terms of Service–Wilson v. Huuuge

I’ve blogged about the Big Fish gambling case before Judge Leighton. He declined to order arbitration in that case, finding that Big Fish waived its right to arbitrate by extensively litigating the case. Judge Leighton is hearing some other similar cases, and he recently declined to send those cases to arbitration, finding that plaintiff was not reasonably on notice. (This post focuses on Judge Leighton’s ruling in the Huuuge case, but there’s another case involving Double Down Interactive where Judge Leighton reached a similar result. Benson v. Double Down Interactive, Case No. 2:18-cv-00525-RBL (W.D. Wash. Nov. 13, 2018).)

The court starts out by noting the plaintiff did not have to click I agree and thus never affirmatively indicated assent. Huuuge, the defendant, did not provide evidence that plaintiff knew about the terms. Instead, it argued the plaintiff had inquiry notice.

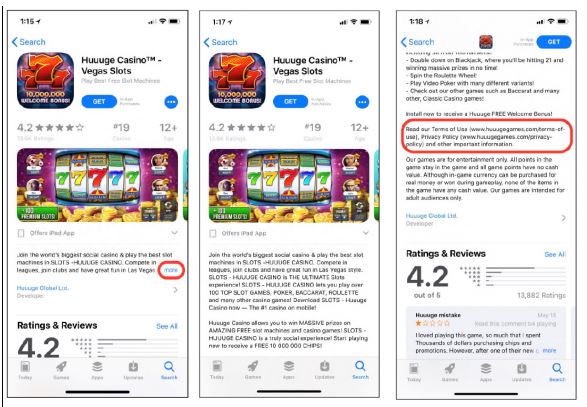

The court says that users can review the terms in two places: (1) when they download the game, and (2) in the “settings” menu. Unfortunately for Huuuge, it takes prospective users several screens to get to the terms, and nothing next to the download button alerts users of the terms.

Access of the terms in the settings area is similarly challenging and not essential to the game. The settings area is not obviously demarcated. And again, nothing apprises the user that there are terms.

The court cited to Nguyen v. Barnes and Noble and Meyer v. Uber Technologies as cases that turn on whether the customer is apprised of the existence of the terms. The court says the result may have been different in the case of Huuuge had the terms appeared next to the download button. The court says the configuration of the download in the app store is even more problematic because the user can download the app when it comes up in search results without even reading the explanatory text (in the full app page).

Huuuge, citing Verio, argued that users played the game multiple times, so they must somehow be on notice. The court says that Verio admitted to awareness of the terms and was actually crawling (albeit using a machine) the entirety of the webpages, including the terms.

Huuuge also makes the argument that users should be presumed to have knowledge of the terms because “everyone knows that all apps comes with terms.” The court says nay:

The Court declines to adopt Huuuge’s suggestion. While online users today are savvier than in the past, this does not mean that the rules of contract law no longer apply. If an app developer wishes to bind a user to their copious terms, the onus is on the developer to at least provide reasonable notice and easy access. This is not a difficult thing to do when designing an app, despite Huuuge’s protestations that the Court should devise some special rule for app store purchases. . . . The fact is, Huuuge chose to make its Terms non-invasive so that users could charge ahead to play their game. Now, they must live with the consequences of that decision.

Ouch.

The court also takes a shot at the fruit stand metaphor that some cases have relied on.

___

The court focuses on the inevitable tension in terms of service implementation. The lawyers want to make the terms of service a hurdle that users cannot access the app without passing. The developers and marketing folks want to make the terms not invasive, so the users can (as the court characterizes it) “charge ahead to play their game”. The latter course of action is risky. Here, it made the difference between being able to send a case to arbitration, potentially avoiding a class action on the one hand, and dealing with full discovery on what could be a very expensive claim, on the other.

Courts have different in their treatment of user expectation with respect to terms. It’s odd from a legal standpoint to see a judge speculate about something that probably varies significantly by generation and age. Here the judge takes a conservative viewpoint and doesn’t credit the app developer with an argument that presumes consumer knowledge of terms. That makes sense in these circumstances.

I’m guessing Huuuge will appeal given that an appeal puts a hold on district court proceedings.

___

Eric’s Comments:

As Venkat notes, this ruling addresses a number of frontiers in online contract formation law:

- contract disclosures buried well below an app’s download button are worthless. This is just a recapitulation of the uncited Specht v. Netscape case from over a dozen years ago

- contract terms buried in an app’s “settings” are worthless

- mere repetitive use of a service isn’t enough to form a contract. The court says: ” a hyperlink may be tucked away in a corner of a website or buried beneath a mountain of text and still be theoretically “available” to a user. While repeatedly playing a game may make it more likely that at some point the ‘Terms of Use’ hyperlink will cross a user’s field of vision, Nguyen specifically held that this is not enough for inquiry notice.” The court goes on to suggest that users may even form “terms blindness” as they grow to ignore seemingly irrelevant parts of the page’s UI.

- despite the ubiquity of online terms, consumers are not presumed to know that contract terms apply to their usage or obligated to go hunting for the disclosures. This is a helpful counterweight to some possibly contrary intimations from the Second Circuit’s Meyer ruling

(Note: this is another case where the court laments the failings of the clickwrap/browsewrap nomenclature: “Courts have also recognized that the labels of ‘clickwrap’ and ‘browsewrap’ do not encompass every type of online consumer contract.” SIGH).

Of course, as an outsider, it seems like all of Huuuge’s arguments are designed to mask Huuuge’s self-inflicted problem. It’s trivially easy to properly form an online contract if there’s a will to do so. So here’s the perennial reminder: if you want to form a contract with users, say it loud and proud. If you try any other approach, the courts won’t take pity on you.

Case citation: Wilson v. Huuuge, Inc., 3:18-cv-05276 (W.D. Wash. Nov. 13, 2018)

Related posts:

Ninth Circuit Reinstates Virtual Platform Gambling Lawsuit Against Big Fish

Federal Court Rejects Online Gambling Lawsuit Against Valve–McLeod v. Valve

Big Fish’s Virtual Casino Doesn’t Violate Washington’s Gambling Statute

Virtual Casino Doesn’t Violate California’s Gambling Law–Mason v. Machine Zone (Guest Blog Post)

Appeals Court Affirms Rejection of Gambling Claims Against Machine Zone

Uber’s Contract Formation Process Fails (Again)–Cullinane v. Uber

Hyperlinking to Sources Can Help Defeat Defamation Claims–Adelson v. Harris

Ninth Circuit Blesses Amazon’s Terms of Service

Browsewrap/Clickwrap Distinction Vexes Another Court–Nevarez v. Ticketmaster

Faulty Mobile Device User Interface Jeopardizes Uber’s Contract Formation–Metter v. Uber

Retailer’s TOS Fails, But New Jersey Warranty Notice Claim Loses Anyway

Court Upholds Airbnb’s Terms of Service–Selden v. Airbnb

Anarchy Has Ensued In Courts’ Handling of Online Contract Formation (Round Up Post)

“Modified Clickwrap” Upheld In Court–Moule v. UPS

Scraping Lawsuit Survives Dismissal Motion–CouponCabin v. Savings.com