23andMe’s Browsewrap Fails, But Its Post-Purchase Clickthrough Works Anyway–Tompkins v. 23andMe

You may recall 23andMe’s legal troubles last Fall, when the FDA launched a big smackdown over selling genetic tests. In the wake of the FDA takedown, the class action lawyers moved in for their cash grab. 23andMe defended with an arbitration clause, but there’s a big problem: 23andMe didn’t display any T&Cs when the consumer purchased its product. So how did 23andMe successfully move this case into arbitration despite its jaw-dropping gaffe? Read on…

The Purchase

The court says 23andMe “customers can enter their payment information and purchase DNA kits online without seeing the TOS.” 23andMe responded that its footer contained a link to “terms of service” containing an arbitration clause, and so it claimed its users were bound to those terms. Judge Koh accurately characterizes this as a “browsewrap” argument and rejects the contract formation:

during checkout, the website did not present or require acceptance of the TOS. Rather, the only way for a customer to see the TOS at that stage was to scroll to the very bottom of the page and click a link under the heading “LEGAL.” Such an arrangement provided insufficient notice to customers and website visitors….there is no evidence that Plaintiffs had or should have had knowledge of the TOS when they purchased their

DNA kits online. Accordingly, 23andMe’s TOS would have been ineffective to bind website visitors or customers who only purchased a DNA kit without creating an account or registering a kit. The Court finds that 23andMe’s practice of obscuring terms of service until after purchase—and for a potentially indefinite time—is unfair, and that a better practice would be to show or require acknowledgement of such terms at the point of sale.

Ouch. It’s pretty harsh seeing a federal judge call the position “unfair,” but she’s 100% right. There’s really no excuse for not including the terms in the purchase process. Just like I’ve always been a little baffled how AOL/Netscape screwed up contract formation in the Specht case, I don’t understand how 23andMe botched this. I’m sure it had competent lawyers, and cross-referencing the TOS during checkout would have been a trivially easy step that would have been 100% legally effective. So what went wrong here? Did the lawyers miss the issue? Did the engineers/UI designers mess up? Did this issue somehow fall through the cracks? Did everyone collectively make an unnecessarily risky business call?

The opinion doesn’t cite the Zappos opinion, but it was factually indistinguishable, and Zappo’s contract formation argument based on footer links similarly failed.

Post-Purchase Registration for Test Results

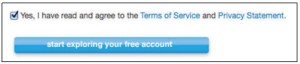

After making the purchase, in order for customers to get their test results, they had to create an online account at 23andMe.com, where they were required to accept a mandatory clickthrough agreement. There’s no argument about the mandatory nature of the clickthrough (but see the discussion about gifts below), and everyone agrees that the text of 23andMe’s TOS didn’t change during the relevant period. The opinion includes a screenshot of the account creation page:

23andMe then made registrants go through an “accept the terms” page. The screenshot from the opinion:

These screenshots look solidly constructed (in fact, only one of the two screens should be necessary to perfect the formation), so we know that 23andMe knows how to properly implement a mandatory clickthrough process. The court says this worked:

Plaintiffs received adequate notice regarding the TOS. As noted above, during the account creation and registration processes, each named Plaintiff clicked a box or button that appeared near a hyperlink to the TOS to indicate acceptance of the TOS. In this respect, the TOS resemble clickwrap agreements, where an offeree receives an opportunity to review terms and conditions and must affirmatively indicate assent. See Specht, 306 F.3d at 22 n.4. The fact that the TOS were hyperlinked and not presented on the same screen does not mean that customers lacked adequate notice.

In fact, 23andMe knew the name of the person associated with the test result, so it could actually show by name that each plaintiff assented online. Legally this is even stronger than the more typical situation where everyone clicks through anonymously.

In response to 23andMe’s contract formation at account registration, the plaintiffs argued that 23andMe’s customers formed a contract at purchase, so the imposition of new legal terms is a proposed amendment that lacked consideration. Check out this response:

The Ninth Circuit has held, in the employment context and under California law, that a “promise to be bound by the arbitration process itself serves as adequate consideration.” Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Najd, 294 F.3d 1104, 1108 (9th Cir. 2002). Under this precedent, 23andMe’s agreement to accept arbitration provided acceptable consideration to its customers. The TOS also provided certain rights to customers, such as a “limited license” to use 23andMe’s “Services” as defined in the agreement. See TOS ¶ 9. Furthermore, in exchange for clicking “I ACCEPT,” customers received the health and ancestry results from their DNA samples. Accordingly, Plaintiffs received sufficient consideration for agreeing to the TOS.

Say what??? This seems to suggest that every mutual arbitration clause is immune from consideration challenges because it automatically provides self-consideration, perhaps on the unstated theory that the parties mutually give up something valuable (the right to litigate). This conclusion would implicitly conflict with the uncited Harris v. Blockbuster ruling. More importantly, it ignores the realpolitik of the situation: in the context of mass consumer contracts, arbitration clauses provide little or no benefit to consumers, so there is not mutuality of consideration in practice. Judge Koh can properly respond that she’s just following Ninth Circuit precedent, but that’s such a ridiculous outcome that I can’t imagine the Ninth Circuit really meant it.

With respect to the other referenced sources of consideration (the license to use the service and access to the test results), arguably 23andMe customers already paid for those services. The court says this is similar to the cyberlaw classic ProCD v. Zeidenberg, but it’s distinguishable because:

23andMe does not argue that the TOS took effect when customers failed to return the DNA kits after a certain period. In typical shrinkwrap cases, the customer tacitly accepts contractual terms by not returning the product within a specified time. E.g., Hill v. Gateway 2000, Inc., 105 F.3d 1147, 1148 (7th Cir. 1997) (upholding contract that became effective when customer did not return product within 30 days). In this case, each named Plaintiff actually agreed to the TOS by affirming “I ACCEPT THE TERMS OF SERVICE,” not by keeping the DNA kit beyond a certain time. Thus, Plaintiffs’ argument that 23andMe’s refund policy was too restrictive does not negate their affirmative assent to the TOS.

This resolution isn’t satisfying because it treats the registration process as a completely new contract, when I see it as an amendment of the existing contract formed when the buyer made the purchase. If it’s an amendment, then the delivery of services can’t provide new consideration because that’s why the buyer bought the services in the first place. As a result, the resolution ignores the buyer’s economic realities. Furthermore, unlike the Zeidenberg and Hill v. Gateway cases, most 23andMe cannot obtain a complete refund by the time they try to access their test results. (Although I don’t recall if in fact a full refund was available in either case. In Zeidenberg, many retailers would not accept returns of opened CDs, and there could have been unreimbursed shipping charges in Hill v. Gateway).

There’s one more problem here that the opinion sidesteps. If someone gave the test kit as a gift, the buyer never agreed to the arbitration clause, even if the gift recipient did enter into the contract. The court even acknowledges this, saying “it is possible for a customer to buy a DNA kit, for example, as a gift for someone else, so that the purchasing customer never needs to create an account or register the kit, and thus is never asked to acknowledge the TOS.” The court never closes the loop to explain why these gifting buyers are shunted to arbitration, even though they never agreed to it.

Unconscionability

The arbitration clause at issue here said:

Applicable law and arbitration. Except for any disputes relating to intellectual property rights, obligations, or any infringement claims, any disputes with 23andMe arising out of or relating to the Agreement (“Disputes”) shall be governed by California law regardless of your country of origin or where you access 23andMe, and notwithstanding of any conflicts of law principles and the United Nations Convention for the International Sale of Goods. Any Disputes shall be resolved by final and binding arbitration under the rules and auspices of the American Arbitration Association, to be held in San Francisco, California, in English, with a written decision stating legal reasoning issued by the arbitrator(s) at either party’s request, and with arbitration costs and reasonable documented attorneys’ costs of both parties to be borne by the party that ultimately loses. Either party may obtain injunctive relief (preliminary or permanent) and orders to compel arbitration or enforce arbitral awards in any court of competent jurisdiction.

The court says that the clause is procedurally unconscionable:

The arbitration provision is a contract of adhesion because it is a standardized clause drafted by 23andMe (who has superior bargaining strength relative to consumers) and presented as a take-it-or-leave-it agreement, giving consumers no opportunity to negotiate any terms….The arbitration provision also involves substantial surprise and oppression. Customers received minimal notice of the arbitration provision, and only after handing over their money.

Nevertheless, the court says that the clause isn’t substantively unconscionable. Among other justifications, the court disregards the unilateral amendment clause in the 23andMe TOS, saying that it was a separate provision from the arbitration clause (but compare Zappos and Blockbuster, among others, which have linked the arbitration clause and unilateral amendment clause). The loser-pays provision in the arbitration clause also gets downgraded in importance because “23andMe represents that it has formally waived any right to recover attorneys’ fees and costs at the request of the AAA.”

Implications

Judge Koh made the dismissal with prejudice, allowing the plaintiffs to immediately appeal the arbitration decision to the Ninth Circuit. I have to imagine they will appeal. This sets up a potential battle royale over online contract formation at the Ninth Circuit, the first really juicy online contract formation squarely presented to the Ninth Circuit in quite some time (the last I could remember is the 2007 case Douglas v. AOL, but perhaps I’m forgetting something more recent). Online contract geeks, fire up your amicus briefs!

[UPDATE: a reader called my attention to the fact that Nguyen v. Barnes & Noble is on appeal to the Ninth Circuit and heard oral arguments in May.]

Although Judge Koh wrote a characteristically sturdy opinion, I would be surprised if her ruling survived an appeal intact. The result is counter-intuitive, so all of my instincts scream that 23andMe f’ed up. As illustrated in this post, Judge Koh made a good number of judgment calls where the Ninth Circuit could justifiably reverse her. That means this case on appeal could very well become a flagship cyberlaw case when the Ninth Circuit gets through with it.

In the interim, I can make a good argument that this is one of the best opinions for teaching online contracts that we’ve seen in the past few years. It has everything you’d want from such an opinion–different formation scenarios, an e-commerce setting, an unconscionability analysis and lots of controversy. Check it out!

Case citation: Tompkins v. 23andMe, Inc., 2014 WL 2903752 (N.D. Cal. June 25, 2014)

Related Posts:

* ‘Flash Sale’ Website Defeats Class Action Claim With Mandatory Arbitration Clause–Starke v. Gilt

* Some Thoughts On General Mills’ Move To Mandate Arbitration And Waive Class Actions

* How To Get Your Clickthrough Agreement Enforced In Court–Moretti v. Hertz

* Court Rules That Kids Can Be Bound By Facebook’s Member Agreement

* Court Blesses Instagram’s Right to Unilaterally Amend Its User Agreement–Rodriguez v. Instagram

* Lawsuit Over Google Hangouts Gutted–Be In v. Google

* Effort to Game Website User Agreement Rules Fails -– Traton News v. Traton Corp.

* JDate Member Agreement Upheld–Zaltz v. JDate (Forbes Cross-Post)

* How Zappos’ User Agreement Failed In Court and Left Zappos Legally Naked (Forbes Cross-Post)

* Barnes & Noble’s Online Contract Formation Process Fails –Nguyen v. Barnes & Noble

* Courts Struggling Needlessly With Online Contracting Practices

* Judge Can’t Decide if Facebook’s User Agreement is a Browsewrap, But He Enforces It Anyways–Fteja v. Facebook

* Court Disregards Check-the-Box Agreement and Doesn’t Enforce Venue Clause — Dunstan v. comScore

* Forum Selection Clause in “Submerged” Terms of Service Presumptively Unenforceable — Hoffman v. Supplements Togo

* Second Circuit Says Arbitration Clause in Terms Emailed After-the-Fact Not Enforceable – Schnabel v. Trilegiant

* Clickthrough Agreement With Acknowledgement Checkbox Enforced–Scherillo v. Dun & Bradstreet

* Contract Formed Even If Customer Never Received It–Schwartz v. Comcast