University-Operated Twitter Account is a Limited Public Forum–Gilley v. Stabin

This lawsuit involves the @UOEquity Twitter account, operated by the University of Oregon’s Division of Equity and Inclusion. During the relevant time period, tova stabin (who styles her name in lowercase) was the communications manager running the account. The account ran a series of posts titled “Racism Interrupters” that asked readers to respond by filling in the blanks to various provocative statements, including this post in June 2022 that says “It sounded like you just said _____. Is that really what you meant?”

Bruce Gilley is a controversial professor at Portland State University, best known for arguing in favor of colonialism. In response to the prompt, he tweeted “all men are created equal.”

Without further context, Gilley’s reply could interpreted a variety of ways. Among other things, the phrase “all men are created equal” comes from our country’s Declaration of Independence, so it’s a core tenet in American principles. However, the phrase excludes over half of society, plus our country’s founding documents didn’t live up to the aspiration of treating “all men” equally. Thus, the phrase is packed with complex meaning. “Defendant stabin testified that she did not disagree with the sentiment ‘all men are created equal’ and in fact agreed with it, though she would prefer to use the gender-neutral term ‘people.'”

However, when considered alongside Gilley’s pro-colonialism work, the phrase could seem like a troll/sealion designed to question whether people should be treated equally. After Gilley’s reply, stabin blocked Gilley from the UOEquity account. In private correspondence, stabin indicated that Gilley “was not just being obnoxious, but bringing obnoxious people to the site some.”

Stabin was trying to spur a conversation among like-minded supporters of DEI, and I could see why she might feel that Gilley’s reply would hijack the conversation and commit microaggressions against the other discussants. However, the First Amendment protects “obnoxious” behavior and people, so stabin needed to proceed more reflectively. The court implies stabin might have characterized Gilley’s response as off-topic, though that wouldn’t be a viewpoint-neutral position.

In July 2022, stabin retired from the university (the opinion doesn’t say if her retirement was accelerated due to this incident). In August 2022, Gilley sued stabin.

The next day, the university unblocked Gilley from the UOEquity account and sent a letter saying “the Division of Equity and Inclusion does not intend to block him or anyone else in the future based on their exercise of protected speech. My office has reinforced to our colleagues who control the University’s multiple social media channels that, if they open such channels to comments, they may not block commentary on the basis of the viewpoints expressed.” Further, “Internal emails show that the University’s general counsel requested that Plaintiff be unblocked immediately unless he engaged in speech ‘not protected by the United States and Oregon Constitutions.'”

Gilley’s lawsuit demanded $17.91 in nominal damages. This unusual amount presumably honors the year our Bill of Rights was enacted, so it’s another troll (just like Musk repeatedly uses 420 and 69). The university attempted to moot the lawsuit by sending Gilley $20 in cash, essentially telling him to keep the change. [FN] However, the $20 bill features the image of known colonialist/racist Andrew Jackson; I might have sent four $5 bills or, better yet, a Harriet Tubman $20 bill (not available yet, unfortunately).

[FN] Given how hard it is for employees to get cash instead of a check due to university bureaucracy, it’s possible that the university didn’t pay. I’ve heard so many lawyers say they would gladly pay the opponent out of their own pockets to make an annoying low-dollar-value lawsuit go away. Perhaps this lawyer actually lived that dream. While the payment in cash made me laugh out loud, it would have become an all-time trollback if the payment amount had matched another important historical date celebrating equality, like $18.63 (the date of the Emancipation Proclamation), $18.68 (when the Equal Protection clause of the Constitution became effective), or $19.54 (the date of Brown v. Board of Education).

Some of the key points from the opinion:

- Even if there’s no threat of imminent future blocking, Gilley’s lawsuit isn’t moot because he’s challenging the university’s social media policies.

- @UOEquity is a limited public forum because the university had guidelines for posting and “a Twitter page is a forum designed for expressive activities.” As a result, “any restrictions on speech in @UOEquity must be reasonable and viewpoint-neutral.”

- “Plaintiff states that he fears he will be blocked or banned from interacting with @UOEquity on Twitter. At the hearing, Plaintiff stated without elaboration that he was self-censoring from interacting with any of the University of Oregon’s Twitter accounts. The Court doubts that Plaintiff is self-censoring out of a genuine fear of consequences….Plaintiff faces no risk of prosecution, professional discipline, or harm to his reputation or employment. As Defendants observe, by self-censoring, Plaintiff is doing nothing more than imposing on himself the consequence he says he fears—a lack of opportunity to interact with the @UOEquity Twitter account.”

- Even if Plaintiff’s post were off-topic (and reasonable minds could conclude that it was not), Defendants still could not block him for expressing a particular viewpoint because to do so would be inconsistent with both the guidelines and the Constitution.”

The court denies Gilley’s request for a preliminary injunction. “Plaintiff has not shown more than a possibility that he will be blocked from interacting with @UOEquity in the future. While he may well succeed in proving that the University violated his First Amendment rights in blocking him in the past, Plaintiff has not shown that the University is likely to do so again.” This differed from the Garnier case: “In Garnier, the defendants repeatedly deleted the plaintiffs’ comments before blocking the plaintiffs on Facebook, and they only unblocked the plaintiffs a few days before trial. This course of conduct shows a sustained commitment to restricting speech that is not present in the matter before this Court.” As a result, Gilley does not get his requested relief now, but he could still win some aspects of the case in future proceedings.

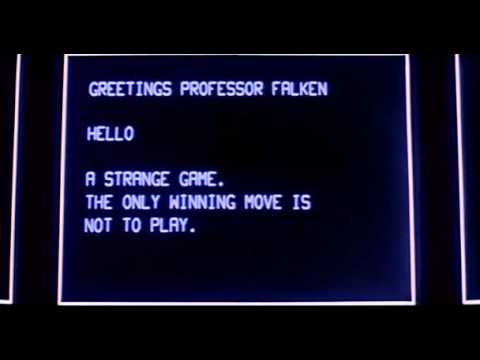

This case says the Twitter account was a limited public forum in this case, though I could see other courts deeming social media accounts as designated public forums. Either way, the ruling emphasizes how hard it is for public institutions to run social media accounts because their content moderation decisions will be fraught with legal peril. Perhaps stabin was overly thin-skinned in her response to Gilley’s post, but fight-or-flight responses are predictable and oh-so-common; government employees routinely respond to garden-variety online trolling as a threat, even when it is well within the lines from a Constitutional standpoint. Ultimately, the DEI office should rethink whether it wants to try to spur social media conversations at all. If it does, it will have to assume the trolls will participate and try to spoil the conversation for the lulz, and any response to the trolling could be limited. Instead, this may be a situation where the only winning move is not to play the game.

Case citation: Gilley v. Stabin, 2023 WL 418155 (D. Ore. Jan. 26, 2023)

UPDATE: The Ninth Circuit reversed the district court. The panel says that Gilley’s challenge wasn’t moot: “Given the policy’s lack of formality and relative novelty, how easily the policy can be reversed, and the lack of procedural safeguards to protect from arbitrary action, the University has not met its heavy burden to show that the conduct cannot reasonably be expected to recur.”

The panel also said that Gilley adequately alleged irreparable injury:

he had been blocked for two months when he first sought injunctive relief. During that time, he sought to learn information on the policy pursuant to which he was blocked without having to petition the courts. The University denied that there was such a policy throughout the period that Gilley remained blocked. The University later disclosed to Gilley its internal social media policy that contained criteria for blocking users and claimed that this policy was operative at the time of Gilley’s blocking. In arguing before us that there was a policy, but that stabin violated it, the University shows that it lacks sufficient policies to prevent such departures from policy by a rogue employee. These facts readily demonstrate irreparable harm

Gilley v. stabin, 2024 WL 1007480 (9th Cir. March 8, 2024).

The panel’s legal standards could be mooted or modified when the pending Garnier and Lindke SCOTUS decisions are issued.

On a slightly related note, Prof. Gilley was hired as a visiting faculty member at New College of Florida, where his offensive-to-many positions are being celebrated by the administration.

JULY 2024 UPDATE: On remand, the lower court granted the following preliminary injunction:

The Communications Manager of the University of Oregon’s Division of Equity and Inclusion, as well as her agents, servants, and employees, and persons in active concert or participation with her who receive actual notice of this injunction ARE HEREBY ENJOINED from (1) hiding, muting, or deleting posts by user @BruceDGilley on the @UOEquity X account because they are “hateful,” “racist,” or “otherwise offensive,” or “out of context,” “off topic,” or “not relevant”; and (2) blocking user @BruceDGilley from interacting with @UOEquity.

Gilley v. Stabin, 2024 WL 3507982 (D. Ore. July 23, 2024)

Related posts:

- Constituent Blocking on Twitter Is Censorship–Felts v. Vollmer

- Catching Up on Government Officials’ Censorship of Constituents on Social Media

- Ninth Circuit: Elected Officials Violated the First Amendment by Blocking Constituents on Social Media–Garnier v. O’Connor-Ratcliff

- Sixth Circuit: Government Official Can Freely Censor Constituents at his Public Facebook Page–Lindke v. Freed

- Constituents Can Sue Chicago Alderman for Blocking Their Facebook Comments–Czosnyka v. Gardiner

- Police Department Can Remove Citizen’s Facebook Comments Calling Cops “Pigs”–Sgaggio v. De Young

- City Government Can’t Remove Off-Topic Comments From Its Social Media Page–Kimsey v. Sammamish

- Does the First Amendment Permit Government Actors to Manage Social Media Comments?–Tanner v. Ziegenhorn

- Law Enforcement’s Efforts to Scrub COVID “Misinformation” Online Violated the First Amendment–Cohoon v. Konrath

- State Legislator Doesn’t Understand That He Works for the Government–Attwood v. Clemons

- Politician Can Block Constituents at Twitter–If It’s a “Campaign” Account–Campbell v. Reisch

- Another Politician Unconstitutionally Censored Constituents on Twitter–Campbell v. Reisch

- When Can a Politician Block Constituents on Social Media?–Garnier v. O’Connor-Ratcliff

- Comments on the Hikind v. Ocasio-Cortez Lawsuit Over AOC’s Twitter Blocks

- Pres. Trump Violates the Constitution By Blocking @RealDonaldTrump Followers–Knight First Amendment v. Trump

- Another Government Impermissibly Censors Constituents on Facebook–Robinson v. Hunt County

- Another Politician Probably Violated the First Amendment By Blocking a Constituent on Twitter–Campbell v. Reisch

- Blocking Constituents from Facebook Page Violates First Amendment–Davison v. Randall

- Kentucky Governor Can Block Constituents on Social Media–Morgan v. Bevin

- President Trump Violated the First Amendment by Blocking Users @realdonaldtrump

- Politician Can’t Ban Constituent From Her Official Facebook Page–Davison v. Loudoun County Supervisors

- Deleting Comments to County Facebook Page May Violate First Amendment–Davison v. Loudoun County

- County Attorney’s Deletion of Constituent’s Facebook Comment May Violate First Amendment

- First Amendment Precludes Disorderly Conduct Conviction for Ranting on Police Department Facebook Page