Priceline Avoids Liability For Resort Fees Due To Its Onsite Disclosures–Singer v. Priceline

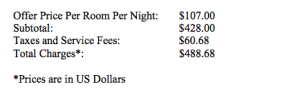

This is a lawsuit alleging that Priceline improperly failed to disclose “resort fees” in connection with its Name Your Own Price service. The service allowed consumers to name a price (bid a dollar amount) for a hotel in a given geographic area and a particular star level (e.g., two nights in downtown Seattle at a four star hotel). The named plaintiff alleged that he was willing to pay $107.00 per room per night in Puerto Rico. Prior to confirming his bid and his card being charged, he was presented by Priceline with the summary screenshotted above.

This is a lawsuit alleging that Priceline improperly failed to disclose “resort fees” in connection with its Name Your Own Price service. The service allowed consumers to name a price (bid a dollar amount) for a hotel in a given geographic area and a particular star level (e.g., two nights in downtown Seattle at a four star hotel). The named plaintiff alleged that he was willing to pay $107.00 per room per night in Puerto Rico. Prior to confirming his bid and his card being charged, he was presented by Priceline with the summary screenshotted above.

The webpage with the disclosure included the following disclaimers under an “Important Information” heading:

- If priceline accepts your price, priceline will book your reservation in a property with an equal or higher star level than you requested. The hotel that is selected may or may not be one that you have seen during a hotel search on priceline. Any sorting or filtering options previously used will not apply to this Name Your Own Price request. Priceline will immediately charge your credit card the total cost of your stay. Rooms purchased through priceline cannot be cancelled, changed or transferred and refunds are not allowed. If your offer is not accepted, your credit cardwill not be charged.

- The reservation holder must present a valid photo ID and credit card at check-in. The credit card is required for any additional hotel specific service fees or incidental charges or fees that may be charged by the hotel to the customer at checkout. These charges may be mandatory (e.g., resort fees) or optional (parking, phone calls or minibar charges) and are not included in your offer price.

Below this disclosure, the plaintiff had to initial a box next to the following text: “I have read, accept and agree to abide by priceline.com’s terms and conditions and privacy policy.” The terms, which contained the following (possibly relevant) language:

“Additional Restrictions”

All hotel reservations are non-cancelable, non-refundable, non-changeable and non-transferable by you. Once you purchase a reservation, your method of payment will be charged for the amount shown – regardless of whether or not the reservation is used. Credit will not be given for any unused reservations and cannot be used toward any future purchases;

Once a priceline.com Request is submitted, it cannot be modified by you; and

Upon check-in, guests must present a valid ID and credit card . . . in their name that is consistent with the transactional details provided to priceline.com (the amount of available credit required will vary by hotel). . . .

You agree that if a hotel accepts your offer, priceline.com will confirm the reservation and charge the entire amount of the stay, including applicable Taxes and Fees (as described below) disclosed to you before submitting an offer, to your method of payment. The price you name is per night and does not include priceline.com’s charge to you for Taxes and Fees.

“Charges for Taxes and Service Fees”.

In connection with facilitating your hotel transaction, we will charge your method of payment for Taxes and Fees. This charge includes an estimated amount to recover the amount we pay to the hotel in connection with your reservation for taxes owed by the hotel including, without limitation, sales and use tax, occupancy tax, room tax, excise tax, value added tax and/or other similar taxes. In certain locations, the tax amount may also include government imposed service fees or other fees not paid directly to the taxing authorities but required by law to be collected by the hotel. The amount paid to the hotel in connection with your reservation for taxes may vary from the amount we estimate and include in the charge to you. The balance of the charge for Taxes and Fees is a fee we retain as part of the compensation for our services and to cover the costs of your reservation, including, for example, customer service costs. The charge for Taxes and Fees varies based on a number of factors including, without limitation, the amount we pay the hotel and the location of the hotel where you will be staying, and may include profit that we retain.

Except as described below, we are not the vendor collecting and remitting taxes to the applicable taxing authorities. Our hotel suppliers, as vendors, bill all applicable taxes to us and we pay over such amounts directly to the vendors. We are not a co-vendor associated with the vendor with whom we book or reserve our customer’s travel arrangements. . . . For transactions involving hotels located within certain jurisdictions, the charge to your debit or credit card for Taxes and Fees includes an additional payment of tax that we are required to collect and remit to the jurisdiction for tax owed on amounts we retain as compensation for our services.

Depending on the property you stay at you may also be charged (i) certain mandatory hotel specific service fees, for example, resort fees (which typically apply to resort type destinations and, if applicable, may range from $10 to $40 per day), energy surcharges, newspaper delivery fees, in-room safe fees, tourism fees, or housekeeping fees and/or (ii) certain optional incidental fees, for example, parking charges, minibar charges, phone calls, room service and movie rentals, etc. These charges, if applicable, will be payable by you to the hotel directly at checkout. When you check in, a credit card or, in the hotel’s discretion, a debit card, will be required to secure these charges and fees that you may incur during your stay. Please contact the hotel directly as to whether and which charges or service fees apply.

The miscellaneous terms also had (1) an entire agreement provision but it said these terms may be superseded by site-specific statements to the extent they are “adequately brought to [the user’s] attention; (2) a statement that the captions are for convenience only.

Breach of contract: Citing to the website disclaimer, the court says that the contract expressly envisions additional charges which the user would be separately required to pay. The court also says that the contract “[breaks] down the “Total Charges” into “Offer Price Per Room, Per Night” and “Taxes and Service Fees.” On this basis the court says it’s clear to the customer that the offer price may not be the final price. The court also dismisses the unjust enrichment claim on the basis that the subject matter is addressed by an express contract (i.e., the terms and conditions and the website disclaimer).

Breach of Duty of Good Faith: The court says that the duty of good faith comes into play where there is a term that is capable of discretionary application or effectuation (in one party’s control). In order to constitute a breach the breaching party must deprive the other party of benefits to which he or she is reasonably entitled; this usually means deception on some level. The court says the claim for breach of the duty of good faith fails. First, plaintiff could not reasonably expect to have the resort fee included because the disclaimer dispels any expectation to the contrary. Plaintiff also advanced the argument that Priceline should not have listed hotels who charged a resort fee among its choices in the first place. The court says that Priceline never represented to the contrary that its options would differentiate between hotels that don’t charge a resort fee and those that do. Again, coming back to the language of the agreement, the court says that plaintiff could not have understood priceline to make this representation.

__

We’ve frequently blogged about the online contracting process (see part 1 and 2 of TOS Arbitration Day at the blog). The question in these cases is whether the customer had read and assented to online terms, and courts typically enforce those terms where the customer is forced to manifest assent before completing the transaction (i.e., checking the box). The court here notes that Priceline required the customer to initial that he or she read and agreed to the terms. While it’s unclear what “initial” means in this context, it provides the requisite indication of assent, so this should be sufficient to support contract formation. Priceline, being a repeat terms of service litigant, has buttoned up its contracting process. Interestingly, the court notes in passing that “[t]he Priceline website did not require a customer to click through the hyperlink to the Terms & Conditions in order to place a bid.” This is the equivalent of a consumer not being forced to scroll through terms to reach the end before expressing assent. Courts have not focused on this in terms of service cases, leaving it to the consumer to ensure that he or she has read terms that the consumer has indicated assent to. The court never discusses in detail plaintiff’s argument that he did not read and agree to the terms, perhaps because it was such an obviously difficult argument.

The case raises a tricky situation for a company that deploys online contracts: how to incorporate statements on the site into the transaction terms (without the downside). Here, the priceline terms said that it may be supplanted by terms located on the site to the extent they were “adequately brought to [the customer’s] attention.” This could have raised the question of whether the disclosure at the point of purchase was sufficiently conspicuous and whether the consumer indication of assent applied to the terms and the hyperlink or the terms at the point of purchase. Customers have raised ambiguity in the manifestation of assent with some success. (See Sgouros v. TransUnion.) The user also had a plausible argument that the point of purchase terms conflicted with the statements in the online terms that carved out only “taxes and fees” which appeared to cover fees paid by the hotel to third parties (government taxes and fees) rather than those the hotel itself charged. The disclaimer also only highlighted to the consumer that the consumer may be required to pay extra charges directly to the hotel, which seems slightly different from what occurred here. Priceline is playing with fire by relying on website terms that may or may not conflict with the default terms of service. Surely it has consumer-friendly marketing copy on its site (e.g., in the form of guarantees). I could see a court easily saying that if the disclaimer in this case formed a part of the parties’ contract, so too did favorable marketing copy that contained consumer-favorable terms. It dodged a bullet here.

Ultimately, I could see how the transaction would not conform to the expectations of the consumer. The point of bidding is to get a deal and certainty in pricing. [Edited: per a comment below the pricing was actually $488 for two rooms for two nights, but not including the additional charges. If you have to pay $488 for two nights for a hotel room that is advertised as $107 per night, that does not seem like such a great reason to use priceline.]

Eric’s Comments: “Resort fees,” and any other similar mandatory hotel-imposed fees that are not included in an upfront reservation fee quoted to consumers, are an abomination. If the FTC doesn’t take action on them, then we need a federal law banning the practice. Otherwise, as we’ve seen over and over, all industry players eventually get sucked into imposing hidden fees to keep their quoted prices comparable to their less scrupulous peers, in which case consumers can no longer do meaningful price comparisons and the marketplace becomes less efficient.

In this case, Priceline used best practices to properly form a contract with users, but the question is whether the resort fee disclosures were properly incorporated into that contract. Normally, buried boilerplate can’t undo a site’s multitudinous sales efforts to leave consumers with a different impression. Here, the court allows Priceline’s onsite disclosures (buried boilerplate plus the reference in the call-to-action) to trump the many ways in which Priceline educated consumers that they get to “name their own price.” It’s easy to see how Priceline’s sales pitches left some consumers confused about the price they’d actually pay.

I’m not planning to sue Priceline, but as Venkat indicates, I no longer use blind bidding systems like Priceline and Hotwire for travel arrangements because of the risk of mandatory hidden costs that I cannot anticipate in my bid. (While mandatory fees are unconscionable, differences in a hotel’s optional fees can also affect my satisfaction with the total price I pay, e.g., parking fees can be $50+/night and therefore a significant chunk of my overall expense. Even things like paid wifi, which other hotels may offer for free, can eat into or eliminate any savings I achieve from bidding down the rack rate). For Priceline and Hotwire to wash their hands of resort fees speaks very poorly about their dedication to their customers’ experience, and this in turn squanders consumer trust and undermines long-term consumer demand for their services. If Priceline or Hotwire really want to create a well-functioning auction system, they must standardize the auctioned offerings so consumers can bid apples-to-apples. Given how the dot com utopian ideal of travel service auctions seems to have largely passed, I’m not expecting the auction sites to make any aggressive consumer-friendly moves in the foreseeable future.

Case citation: Singer v. Priceline, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 95617 (D. Conn. July 22, 2016)

Related posts:

Online Marketplace Isn’t Liable for Bad Conduct by Merchants It Certifies–Englert v. Alibaba

Courts Approve Terms of Service-Based Arbitration Clauses for Uber and Groupon

“Modified Clickwrap” Upheld In Court–Moule v. UPS

Ninth Circuit Rejects Plaintiffs’ Bad Misreadings of eBay’s User Agreement–Block v. eBay

eBay Not Liable for Technical Glitch When Seller Doesn’t Set Reserve Price — D’Agostino v. eBay