You Can’t Buy A Copyright Just To Bury It–Katz v. Chevaldina (Forbes Cross-Post)

In the United States, copyright law principally serves as an economic policy by protecting creators’ ability to recoup the investments they make in generating new works that have value to society. As a result, copyright law gets weird when it’s asked to advance non-economic objectives.

This is particularly true when copyright is deployed as a pseudo-privacy law to create Internet memory holes. In the past few years, we’ve seen an uptick in attempts to use copyright law as a “right to be forgotten,” i.e., to scrub unwanted content from the Internet. There are a few different ways to do this, but here’s one approach: a person buys the copyright to third-party content about him/herself and then threatens infringement against republishers in an effort to remove the content. This may sound consistent with copyright doctrine, but we’re learning that it doesn’t work in practice.

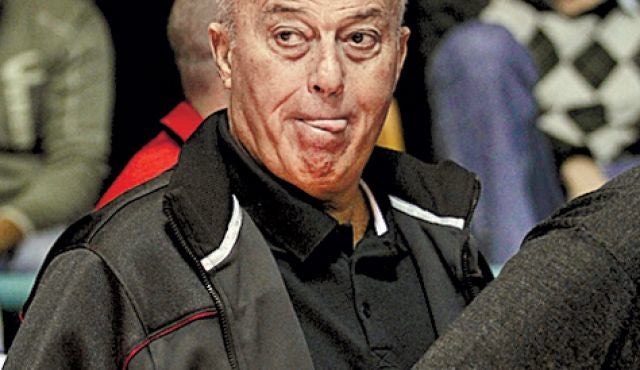

Raanan Katz owns a lot of real estate plus part of the Miami Heat basketball team. At an Israeli basketball practice, a third-party photographer, Seffi Magriso, took this photo:

Flattering? Probably not. As the court describes it, Katz’s “tongue protrudes askew from his mouth.” Worth a federal lawsuit? Not to most of us. However, if you’re wealthy and vain enough, you might be willing to burn some money trying to scrub it.

Irina Chevaldina is an unhappy former tenant of Katz’s company. She ran a blog critical of Katz. She copied Magriso’s photo without permission and repeatedly reposted it on her blog, sometimes with commentary, sometimes not. Unhappy about this, Katz acquired the photo’s copyright and then claimed Chevaldina infringed his newly acquired copyright.

The district court rejected Katz’s suit. In a short per curiam opinion, a federal appellate court confirmed that Chevaldina’s photo republication constituted fair use, using the standard four-factor test from the statute:

1) Nature of the use. Chevaldina did not make a commercial use because “Chevaldina unabashedly criticized and commented on the dealings of Katz, his businesses, and his lawyers. Chevaldina’s blog posts sought to warn and educate others about the alleged nefariousness of Katz, and she made no money from her use of the photo.” She also made a transformative use because “she used Katz’s purportedly ‘ugly’ and ‘compromising’ appearance to ridicule and satirize his character.”

2) Nature of the work. “While Magriso’s photojournalistic timing was fortuitous (at least from Chevaldina’s perspective), this alone was not enough to make the creative gilt of the Photo predominate over its plainly factual elements.” Plus, the photo had already been published.

3) Amount and substantiality of portion taken. Even though Chevaldina sometimes posted the photo verbatim, truncating or redacting the photo would have interfered with its communicative message. (This is true in most cases involving photos).

4) Marketplace effect:

Chevaldina’s use of the Photo would not materially impair Katz’s incentive to publish the work. Katz took the highly unusual step of obtaining the copyright to the Photo and initiating this lawsuit specifically to prevent its publication. Katz profoundly distastes the Photo and seeks to extinguish, for all time, the dissemination of his “embarrassing” countenance. Due to Katz’s attempt to utilize copyright as an instrument of censorship against unwanted criticism, there is no potential market for his work

The court concludes that the analysis “tilts strongly in favor of fair use” and “every reasonable factfinder would conclude the inclusion of the Photo in her blog posts constituted fair use.” Thus, the court rejects Katz’s lawsuit.

While fair use analyses are heavily fact-specific and vary from case-to-case, this court’s factor-by-factor analysis should apply equally in most circumstances where someone buys a third party’s copyright just to suppress it. That’s especially true with the fourth factor, where judges–applying equitable legal principles–will instinctively resist using “copyright as an instrument of censorship against unwanted criticism.”

Counsel for Chevaldina sent me the following comment: “Naturally, we are delighted with the opinion. Hopefully, this will give pause to those, like Mr. Katz, who want to use their wealth, the legal system in general, and copyright law in particular, to suppress criticism of them.”

Separately, in August, the district court granted Chevaldina’s request for attorneys’ fees under copyright law’s discretionary fee-shifting provision. Compared to the appellate court’s neutrally-worded analysis, the district court criticized Katz’s lawsuit harshly:

During the more than two years that this litigation consumed, Plaintiff should have at all times known his claim would eventually fail when the truth of his motivations was eventually known….

it is crystal clear that Plaintiff’s motivations pursuing this lawsuit were improper. Instead of using the law for its intended purposes of fostering ideas and expression, Plaintiff obtained the photograph’s copyright solely for the purpose of suppressing Defendant’s free speech….While Plaintiff might view it necessary to remove his unflattering picture to “stop this atrocity”, he may not resort to abusive methods to do so.

Plaintiff purchased the photograph taken of himself only after Defendant’s use, then registered the copyright in an effort to prohibit Defendant from using the photograph in her critical blog of Plaintiff. Plaintiff filed this action only to prevent Defendant from using the photograph, and had no intention of marketing the photograph. Essentially, as Judge McAliley found, Plaintiff had no purpose for purchasing or copyrighting the photograph other than this litigation.

In this manner, Plaintiff attempted to use the Copyright Act for purposes wholly unrelated to the law’s purpose of fostering the marketplace of ideas….

Because Plaintiff failed to support his pleadings, continues to vigorously pursue a claim without any merits, in the face of meritorious defenses, this Court recommends that awarding attorney’s fees to Defendant promotes considerations of compensation and deterrence. To do otherwise would encourage continued abuse of the Copyright Act as a tool for stymieing free expression.

On that basis, the court ordered Katz to pay Chevaldina about $155k in attorneys’ fees and court costs. Katz can surely afford to write the check. Nevertheless, his quest to suppress “embarrassing” content about himself failed spectacularly on two fronts. First, his lawsuit triggered the Streisand Effect, so now many more people have seen the purportedly embarrassing photo. Second, no matter how embarrassing the photo is, I think his litigation choices are way more embarrassing to him. The photos only showed what he looked like on the outside; the litigation campaign revealed much about what’s inside.

Due to the decisive appellate ruling and the district court’s stinging rebuke and fee-shift, the results of this lawsuit should deter other people from buying up copyrights to manufacture a right to forget. Unfortunately, the temptation of seemingly being able to control one’s public image is so strong that I expect we’ll see more overreaching copyright cases like Katz’s in the future.

Case citation: Katz v. Google Inc., 2015 WL 5449883 (11th Cir. Sept. 17, 2015)

Some Related Posts:

* Big Fee Shift in Unsuccessful Copyright Lawsuit To Suppress Unflattering Photo–Katz v. Chevaldina

* Griping Blogger Can Show Photo Of Griping Target–Katz v. Chevaldina

* Blogger Can’t Defeat Copyright Infringement Claim on Motion to Dismiss–Katz v. Chevaldina

* Another Blogger Wins a Fair Use Defense For a Photo–Leveyfilm v. Fox Sports

* The Latest Attempt to Use Copyright Law to Remove Negative Consumer Reviews–Small Justice v. Xcentric

* Griping Blogger Protected by Fair Use But Not Section 230–Ascend Health v. Wells

* The Dangerous Meme That Won’t Go Away: Using Copyright Assignments to Suppress Unwanted Content–Scott v. WorldStarHipHop