Another Shill Article Tries to Normalize the SAD Scheme

I note the posting of a draft article, which (unfortunately) has been accepted for publication by the Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal, entitled “Beyond the Brick-and-Mortar Paradigm: The Legal and Procedural Foundations of Schedule A Litigation in Combating Online Counterfeiting as Distinct from Traditional Trademark Enforcement.” The article seeks to normalize the SAD Scheme.

I note the posting of a draft article, which (unfortunately) has been accepted for publication by the Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal, entitled “Beyond the Brick-and-Mortar Paradigm: The Legal and Procedural Foundations of Schedule A Litigation in Combating Online Counterfeiting as Distinct from Traditional Trademark Enforcement.” The article seeks to normalize the SAD Scheme.

[As usual, I don’t link to pieces that aren’t worth reading. Indeed, I lament giving the article any attention at all.]

[JANUARY 2026 UPDATE: the article is no longer forthcoming in that journal.]

This article adds to the tiny pro-SAD Scheme literature, which appears to be growing inorganically. The last time I covered the genre, I mentioned a student note titled “Schedule A Cases. Not Sad at All.” The student-author was clerking for a rightsowner-plaintiff firm that had filed dozens of SAD Scheme cases, but the note didn’t disclose that affiliation. In my opinion, the undisclosed relationship corrodes the note’s credibility.

This article’s disclosed co-authors are an adjunct professor and student affiliated with Michigan State’s “Center for Anti-Counterfeiting and Product Protection” (the “A-CAPP” center). The article’s SSRN page–but not the piece itself–makes this disclosure:

Funder’s statement

Greer Burns and Crain partially funded the research through a research gift to the Center for Anti-Counterfeiting and Product Protection.

Greer Burns and Crain is a law firm closely associated with filing SAD Scheme cases. Two of its shareholders (including Amy Ziegler, discussed below) hold officer positions in a recently created vanity “bar association” (the “SAFE Bar Association”) designed to normalize the SAD Scheme. To supplement those efforts, the law firm is funding research that it can and will cite in court filings to help normalize its practices.

Due to Greer Burns’ funding support for the research, I view this article as a shill article. Even though the funding is publicly disclosed somewhere (but not in the article itself), its shillness still corrodes the article’s credibility.

[Note: If the journal knows about Greer Burns’ funding support for the research, I expect the journal’s editors will require the authors to incorporate the funding disclosures in the article itself, and not just display the disclosure on the article’s SSRN page. However, because the disclosure isn’t in the article file posted to SSRN, I’m wondering if the journal’s student editors knew about Greer Burns’ funding support when they accepted the piece for publication?]

If you enjoy consuming shill advocacy, I recommend watching some OG 1980s infomercials instead of reading this article.

In addition to the funder’s statement, the article’s SSRN page (but not the article itself) declares A-CAPP’s purported independence:

WE ARE INDEPENDENT: Our research and related work are independent. Although we raise funding for our research and other activities as a self-sustaining unit at Michigan State University through gifts and contracts, we do not accept funding that would require us to promote a specific viewpoint or perspective. We proactively seek to be knowledgeable about current events and updates in our field and produce research and resource tools applicable in the practice of brand protection.

I don’t find this declaration believable. A-CAPP bakes the advocacy of “a specific viewpoint or perspective” into the center’s architecture. Per its title, the center is biased towards “anti” counterfeiting. My concerns about the center’s structural bias are exacerbated when the center produces a work that commercially benefits a funding supporter.

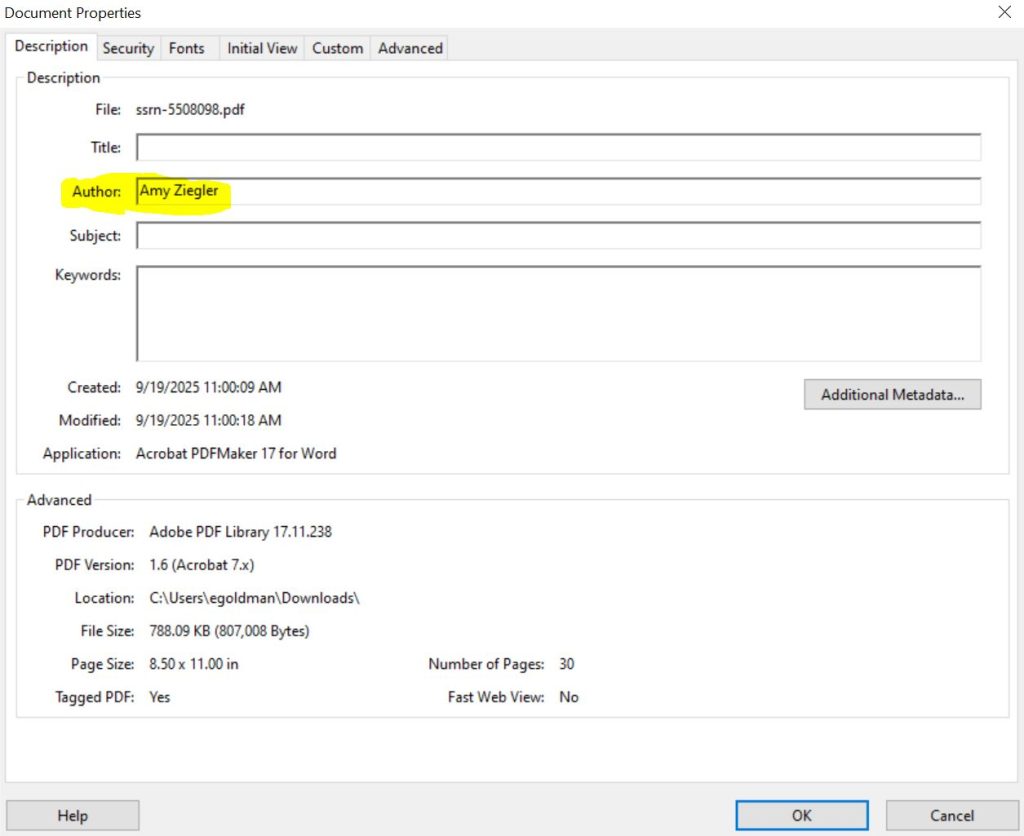

In addition to my general skepticism about A-CAPP’s self-declared independence, I have questions about the authors’ independence with respect to this article specifically. In the article PDF I downloaded from SSRN, the document properties metadata lists Amy Ziegler as the document’s author:

Amy Ziegler is a shareholder at Greer Burns & Crain who frequently files SAD Scheme cases. She is president of the vanity bar association trying to normalize the SAD Scheme. The article does not list her as a co-author.

I hypothesized several possible explanations for why Amy Ziegler might be listed as the article PDF’s author:

- Hypothesis 1: This is a false flag operation where the disclosed authors manufactured this evidence to confuse readers like me.

- Hypothesis 2: The disclosed authors completely wrote the article independently but, at the last step, Amy converted the file into the final PDF.

- Hypothesis 3: The disclosed authors of the article started their authorship journey using a file provided by Amy but then completely wrote the content from scratch.

- Hypothesis 4: Amy provided an outline or starting point that the disclosed authors expanded into the final text.

- Hypothesis 5: Amy is an undisclosed co-author.

- Hypothesis 6: Amy ghost-wrote the piece and the disclosed authors are window-dressing.

You can decide for yourself which of these hypotheses (or maybe one that didn’t occur to me) seems most plausible to you. To me, this feels like an Occam’s Razor situation.

Related questions: Which of the six hypotheses, if true, would negate the disclosed authors’ self-declarations of “independence”? And if hypothesis 4, 5, or 6 is true, what should the journal do in response?

* * *

Some of the article’s structural flaws:

1) In the first paragraph, the article says “We limit our review to trademark counterfeiting enforcement brought under Schedule A cases.” There are at least two major problems with this framing.

First, according to my (admittedly rough) calculations, about 30% of SAD Scheme cases are now copyright and patent cases, which the article completely ignores. So the article makes some sweeping generalizations about the SAD Scheme by ignoring a major chunk of the actual activity taking place in court.

Second, just because a rightsowner-plaintiff claims their case is a trademark “counterfeiting” case doesn’t mean it’s actually a counterfeiting case. See Prof. Fackrell’s treatment of this point. Until a judge has independently and properly reviewed the plaintiff’s assertions, we don’t know whether a particular SAD Scheme litigation involves counterfeiting, “traditional” trademark enforcement, trademark trolling, trademark bullying, or something else. (The SAD Scheme has been associated with all of these activities). We can only know if a case is truly a “counterfeiting” case at the end of the judicial process, not the beginning. In other words, SAD Scheme cases pose a classification problem (are they meritorious or not, and if so, on what grounds?) that cannot be answered based solely on the plaintiff’s self-representations.

Fortunately, the American judicial system is built around a venerable and reliable method to evaluate the veracity of plaintiffs’ self-representations: it’s called due process, and we desperately need more of it, not less. The bending or suspension of due process evaluations of plaintiff self-representations is my most fundamental problem with the SAD Scheme.

Fortunately, the American judicial system is built around a venerable and reliable method to evaluate the veracity of plaintiffs’ self-representations: it’s called due process, and we desperately need more of it, not less. The bending or suspension of due process evaluations of plaintiff self-representations is my most fundamental problem with the SAD Scheme.

2) The article makes many factual claims without citations. I imagine the student journal editors will push back on some of those unsubstantiated fact claims. However, the cite-checking process will surely expose that some claims are factually unsupportable and need to be revised or deleted.

3) The article repeatedly characterizes the SAD Scheme as equitable and just, which suggests the authors have a very different conception of due process than I do.

These hortatory statements are also tone-deaf to the SAD Scheme’s real-world victimization. See the Bonus 2 appendix below for one victim’s side of the story. The authors unceremoniously and unjustly erase those victims’ experiences from the discourse.

The SAD Scheme has entered its death spiral because judges increasingly realize its illegitimacy (and regret their prior acquiescence). Shill efforts won’t reverse this downward spiral. Instead, anyone hitching their reputations to this illegitimate practice, especially at this late date, seems likely to be judged poorly by history.

The SAD Scheme has entered its death spiral because judges increasingly realize its illegitimacy (and regret their prior acquiescence). Shill efforts won’t reverse this downward spiral. Instead, anyone hitching their reputations to this illegitimate practice, especially at this late date, seems likely to be judged poorly by history.

* * *

Rather than do a complete fisking of the article, I’ll critique about 20 lowlights:

__

Shill article: “some argue that online counterfeit sales are overstated and that the majority of Schedule A cases target innocent trademark infringers.”

My comment: My article is the sole citation for the “some” claim, but my article does not support either point.

__

Shill article: “The online sale of counterfeits is often more deceptive than a physical marketplace, where a consumer has a chance to inspect and hold a good before purchase, and exposes any consumer (individual or corporate) who is purchasing branded goods online to potential harm, both physical and financial.”

My comment: [Citations needed].

__

Shill article: “In cases involving large numbers of third party online sellers who either have not been required to provide identifying information to a platform, have obstructed or falsified information, or whose information is otherwise available [sic], the only information that may be available are their marketplace account credentials or domain names.”

My comment: Producing this information was the point of the INFORM Consumers Act. The article later decries a perceived underenforcement of the INFORM Consumers Act, but the article doesn’t address the degree to which the law redressed this concern.

__

Shill article: “plaintiffs can request that the judge seal the complaint to ensure the sellers do not attempt to move or conceal their assets.”

My comment: The article just claimed that “the only information that may be available [about the defendants] are their marketplace account credentials or domain names.” In those circumstances, what evidence would a rightsowner-plaintiff have that the sellers will attempt to move or conceal their assets?

__

Shill article: Trying to refute my criticisms of robo-pleading, the article claims “The use of legal templates is a standard practice among lawyers in the U.S. that serves many purposes including efficiency.”

My comment: It’s fine for lawyers to use templates. However, whatever starting point they use, the lawyers still need to make defendant-specific factual assertions that comport with Rule 11. I’ve seen too many SAD Scheme cases that do not clear that foundational hurdle.

__

Shill article: “defendants are listed in ‘Schedule A’ and identified by their domain name, seller alias, or online store name, which is often the only identifying marker that the plaintiff can access without a court order. We argue that this is appropriate.”

My comment: The sentence “We argue that this is appropriate” is the sum total of the argument supporting its conclusion. High quality stuff.

__

Shill article: The article tries to normalize SAD Scheme joinder: “before a suit is filed, the plaintiff has no methods to verify with certainty which online sellers are owned by a single entity or individual, since it cannot access or compel that information from the platforms or website hosts prior to filing a complaint.”

My comment: This is not complicated. If rightsowner-plaintiffs don’t have these facts at the time of filing, then the plaintiffs can’t assert that the defendants have common interests.

__

Shill article: “Critics claim, however, that joinder in these cases deprives the court of filing fees. This is an irrelevant argument for rejecting joinder of defendants.”

My comment: I assume I’m one of the “critics” in this sentence, though the fact claim doesn’t have any citation. I never argued that the filing fees are a basis for rejecting joinder, but I did point out that misjoinder provides an undeserved financial subsidy to rightsowners at taxpayer expense.

__

Shill article: If “plaintiffs filed separate actions for each individual infringement in Schedule A cases, the entire court system would become bogged down.”

My comment: This is an obvious strawman argument because the rightsowners have repeatedly indicated they wouldn’t sue every SAD Scheme defendant if they had to pay the full costs of litigating against them. But also, it’s true that due process is costly and time-consuming.

__

Shill article: “In the spirit of joinder, a broad definition of ‘series of transactions or occurrences’ in the context of online trademark counterfeiting is critical for effective enforcement. We do not believe it should be limited to the more narrow readings.”

My comment: Is the goal of the judicial system to enable “effective enforcement,” or is it to balance multiple competing interests in a manner consistent with due process?

_

Shill article: “Schedule A cases often exhibit screenshots evidencing the sale of the alleged counterfeit goods online. The infringement is obvious from the screenshot evidence, which is what Schedule A case evidence standards should be confined to. These are not complex intellectual property disputes between two legitimate companies.”

My comment: Like toddlers, some rightsowner-plaintiffs apparently need to learn how to use their words. A screenshot can provide supporting evidence of infringement, but it always needs explanation. That’s especially true in design patent cases, where a visual comparison between two items (without more) doesn’t prove infringement, and when defendants use dictionary words in their product descriptions.

Also, the claim that “These are not complex intellectual property disputes between two legitimate companies” needs citation. Without further qualification, the generalization is demonstrably false. The only way we know if the defendant is legitimate or not, and if the IP dispute is simple or complex, is if the defendant shows up and tells its story. Otherwise, this fact claim is at best a wild guess. It’s clearly not true in numerous cases I’ve blogged. Instead, rightsowner-plaintiffs can only make this claim consistent with Rule 11 if they do adequate defendant-specific investigations. (Recall, these authors claim the only thing the plaintiffs know about the defendants is the merchant aliases, which isn’t enough to make any inference about the defendant’s legitimacy and the matter’s complexity).

__

Shill article: The article continues to try to justify screenshots as evidence by comparing it to the evidence attached to 512(c)(3) copyright takedown demands: “Unless there is a question as to whether that copyrighted image is valid, notice and takedown requests typically are typically respected and adhered to without requiring further evidence when there is an obvious infringement.”

My comment: Wow, that’s quite an apples-to-oranges analogy. The services don’t honor copyright takedown notices because the screenshots are persuasive evidence of infringement; the services take down content essentially on demand to preserve their 512 safe harbor defense. As a result, DMCA-induced overremovals have been extensively documented.

Also, 512 is an extrajudicial process where Congress waived due process requirements, while the SAD Scheme takes place in a judicial system that must comply with due process. So this is an obviously false equivalence.

__

Shill article: “If a judge feels that it is difficult to evaluate the merits of the claim that a plaintiff asserts, instead of refusing to evaluate it, the judge should request additional evidence from the plaintiff in lieu of simply rejecting a claim.”

My comment: Rightsowner-plaintiffs are requesting extraordinary relief in an ex parte TRO proceeding. The defendants aren’t around to contextualize the screenshots or otherwise defend their interests. The screenshots may consist of hundreds of pages. If plaintiffs want the benefits of an ex parte process, they have to do the work to prepare the case properly. The judge isn’t there to do their work for them.

__

Shill article: “Schedule A cases address clear-cut instances of sales of counterfeits, where infringement is readily apparent from online sales listings and screenshot evidence.”

My comment: These fact claims have no citation support, nor could they because the claims are obviously overbroad.

__

Shill article: “The inherent nature of trademark counterfeiting online with third-party sellers located outside of the U.S. presents specific facts that make proceeding with a TRO on an ex parte basis appropriate.”

My comment: How do the plaintiffs or the judges know the defendants are outside the US? Recall the article previously said the plaintiffs just know the merchant’s alias. In fact, numerous US defendants have been ensnared in the SAD Scheme.

__

Shill article: “online trademark counterfeiters are bad actors and broad injunctive relief is an appropriate remedy.”

My comment: Lawyers who disrespect due process are also bad actors.

__

Shill article: “Allowing for damages and attorney fees reinforces that brand protection must be pursued responsibly, with respect for due process and the equitable treatment of all parties.”

My comment: [Record-scratch] Can we go back over that part where the SAD Scheme allegedly demonstrates “respect for due process and the equitable treatment of all parties”?

__

Shill article: “Potentially due to negative backlash from some scholars, courts have begun to shy away from accepting Schedule A cases as the most equitable and just avenue for plaintiff-rightsholders to protect their marks.”

My comment: I am one of the “some scholars.” My mom would be so proud. However, I only dream of having that much influence over the judicial system LOL. Also, more record-scratches on the “most equitable and just avenue” assertions. “Equitable” and “just” to whom?

__

Shill article: “Schedule A cases provide a critical enforcement mechanism—one that balances efficiency with equity, and deterrence with accountability.”

My comment: Again, I ask: “equity” and “accountability” for whom?

__

UPDATE: Prof. Fackrell has identified another place where the article mishandled its characterization of the cited evidence.

* * *

BONUS 1

Another student note I haven’t referenced earlier: Lei Zhu, Made in China, Sued in the U.S.: The Exploitation of Civil Procedure in Cross-Border Ecommerce Trademark Infringement Cases, 34 Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law 139 (2023). A summary:

First, the U.S. plaintiffs’ email service to the Chinese defendants likely violates due process protected by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (“FRCP”). Second, the courts that rendered the most recent rulings likely lacked jurisdiction over the Chinese sellers. Third, the common occurrence of U.S. plaintiffs filing joint lawsuits against a massive number of Chinese sellers likely fails to conform to the FRCP’s joinder rules. Fourth, the preliminary injunctions against the Chinese sellers are often hastily granted by U.S. courts despite key procedural requirements not being satisfied. These four procedural issues often go unlitigated because Chinese sellers rarely appear in U.S. courts, which is arguably the reason why the plaintiffs initiate such suits. U.S. federal courts and the U.S. legal system thus has become a part of U.S. corporate strategy to gain windfall remedies.

* * *

BONUS 2

[Lynette Forgan, a SAD Scheme victim, sent me this draft media release about 2 years ago (so some of the details are now a little dated). We never got around to circulating it. I’m posting it now because it describes the experience of a SAD Scheme victim–the experience that the shill article erases from the equation.]

The United States Federal Government has lost an estimated quarter of a billion dollars to date, due to an abusive but little-known form of litigation dubbed the SAD Scheme.

The Schedule A Defendants (SAD) Scheme targeting intellectual property (IP) infringements, has come to the attention of Internet Law Professor Eric Goldman.

Professor Goldman is Professor of Law, Associate Dean for Research, Co-Director of the High Tech Law Institute, and Co-Supervisor of the Privacy Law Certificate at the Santa Clara University School of Law.

He said the SAD Scheme abuses many innocent online businesses. “The SAD Scheme exploits weak spots in the law to demand thousands of dollars in penalties from online businesses, with substantial assistance from judges.”

Professor Goldman said the SAD Scheme enabled lawyers, acting for their clients, to file a temporary restraining order (TRO) against hundreds of alleged offenders “en masse” while paying only a single court filing fee of a few hundred dollars.

The SAD Scheme operates most frequently in the Northern District of Illinois, and has already impacted hundreds of thousands of sellers, costing the Federal Government some $250 million in lost court filing fees.

Professor Goldman said the SAD Scheme undermined intellectual property and civil procedure rules.

“A single temporary restraining order results in online marketplaces such as Etsy, Ebay etc, freezing the entire account of the online businesses targeted, rather than just the item allegedly infringing IP rights.

“The SAD scheme is designed to cost-effectively target online infringers, especially when the alleged infringers are located in China or other foreign countries and hide their identities and locations.

“The reality however, is that the SAD Scheme bypasses standard legal safeguards. It imposes substantial costs on online marketplaces, consumers and the courts, causing extreme financial hardship and emotional distress to many innocent parties.”

* * *

A small “single desk” operator on Australia’s Gold Coast, Lynette Forgan, who runs online hobby shop Impact Australia Designs [now offline–see postscript below], selling handmade, upcycled and vintage items on Etsy, said her shop was shut down twice in two years by AM Sullivan Law.

“My Etsy shop was shut down in September 2021 and again in April 2022, when my Australian PayPal was also shut down.

“An “en masse” temporary restraining order (TRO) against myself and hundreds of other online operators, was filed in the Northern District of Illinois by AM Sullivan Law on behalf of Fleischer Studios, and this shut down our entire shops comprising thousands of unrelated items.

“The total filing fee cost the lawyers just a few hundred dollars. In the meantime, victims were pressured to pay thousands of dollars to get their businesses back up and running.

“I was told: ‘If you do not wish to litigate this matter in court, we can still offer you a settlement, which will allow you to get your account back and to have the case dismissed against you.’

“In 2021, I was given 21 days to defend myself, in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. This was during the COVID pandemic shutdown when severe travel restrictions were imposed worldwide.

“I maintained that I was completely innocent of all charges and refused to pay the ransom demands. After many weeks of nail biting emails outlining my position to AM Sullivan, I was released from the TRO. Many others, however, were forced to pay up whether they were infringing copyright or not. The bullying and abuse of the system caused me to suffer an emotional breakdown, but I refused to give in to such unreasonable demands.”

Ms. Forgan said all that was required to target a business was for a legal team to claim the business had infringed a client’s intellectual property, then add that business to a long list of alleged offenders, file this under one TRO, and watch as panic payments rolled in.

“I am totally in favor of protecting copyright, but this in my opinion, is an unfair and unconscionable abuse of the legal system and needs to be stopped immediately.

“The SAD Scheme instead, is growing in popularity and is becoming a “get rich quick” form of ambulance chasing.”

* * *

Professor Goldman said hundreds of thousands of merchants had been affected.

“I have heard so many similar stories to Ms. Forgan’s – it’s heartbreaking.”

He said TROs were not supposed to last longer than fourteen days.

“But online marketplaces may maintain the account freeze indefinitely.” He said the TRO freeze harmed defendants in two ways:

“First, the freeze locks up any cash being held by the online marketplace. This freeze can cause severe or fatal cash-flow problems for the defendant, which may not be able to pay its vendors, employees, or lawyers.

“Second, the freeze prevents the merchant from making future sales—particularly unchallenged non-infringing items.

“In my view, this is a serious abuse of the legal system.”

[Postscript: I checked with Lynette over the weekend and she sent me this update: “The SAD Scheme resulted in me closing my online shop, and the distress and idiocy of this flawed system caused such erosion of confidence in the judicial system.”]

* * *

Prior Blog Posts on the SAD Scheme

- Court Sanctions Plaintiff’s Lawyer for Unverified Claims That the Defendant Was Hiding–Guangzhou Youlan Technology Co. Ltd. v. Onbrill World

- SAD Scheme Cases Are a Cesspool of IP Owner Overreaches–Nike v. Quanzhou Yiyi Shoe Industry

- District of New Jersey Adopts SAD Scheme Standing Order

- Court “Sanctions” SAD Scheme Judge Shopping—Crimpit v. Schedule A Defendants

- Chicago-Kent SAD Scheme Symposium TOMORROW

- Amicus Brief Urges Seventh Circuit to Award Attorneys’ Fees in SAD Scheme Case–Louis Poulsen v. Lightzey

- Court Rejects Schedule A Claims Against Sellers of Compatible Parts/Accessories (Cross-Post)

- Judge Kness: the SAD Scheme “Should No Longer Be Perpetuated in Its Present Form”–Eicher Motors v. Schedule A Defendants

- SAD Scheme Lawyers Sanctioned for Judge-Shopping–Dongguan Deego v. Schedule A

- Judge Ranjan Cracks Down on SAD Scheme Cases

- Because the SAD Scheme Disregards Due Process, Errors Inevitably Ensue–Modlily v. Funlingo

- SAD Scheme-Style Case Falls Apart When the Defendant Appears in Court—King Spider v. Pandabuy

- Serial Copyright Plaintiff Lacks Standing to Enforce Third-Party Copyrights–Viral DRM v 7News

- Another N.D. Ill. Judge Balks at SAD Scheme Joinder–Zaful v. Schedule A Defendants

- Judge Rejects SAD Scheme Joinder–Toyota v. Schedule A Defendants

- Another Judge Balks at SAD Scheme Joinder–Xie v. Annex A

- Will Judges Become More Skeptical of Joinder in SAD Scheme Cases?–Dongguan Juyuan v. Schedule A

- SAD Scheme Leads to Another Massively Disproportionate Asset Freeze–Powell v. Schedule A

- Misjoinder Dooms SAD Scheme Patent Case–Wang v. Schedule A Defendants

- Judge Hammers SEC for Lying to Get an Ex Parte TRO–SEC v. Digital Licensing

- Judge Reconsiders SAD Scheme Ruling Against Online Marketplaces–Squishmallows v. Alibaba

- N.D. Cal. Judge Pushes Back on Copyright SAD Scheme Cases–Viral DRM v. YouTube Schedule A Defendants

- A Judge Enumerates a SAD Scheme Plaintiff’s Multiple Abuses, But Still Won’t Award Sanctions–Jiangsu Huari Webbing Leather v. Schedule A Defendants

- Why Online Marketplaces Don’t Do More to Combat the SAD Scheme–Squishmallows v. Alibaba

- SAD Scheme Cases Are Always Troubling–Betty’s Best v. Schedule A Defendants

- Judge Pushes Back on SAD Scheme Sealing Requests

- Roblox Sanctioned for SAD Scheme Abuse–Roblox v. Schedule A Defendants

- Now Available: the Published Version of My SAD Scheme Article

- In a SAD Scheme Case, Court Rejects Injunction Over “Emoji” Trademark

- Schedule A (SAD Scheme) Plaintiff Sanctioned for “Fraud on the Court”–Xped v. Respect the Look

- My Comments to the USPTO About the SAD Scheme and Anticounterfeiting/Antipiracy Efforts

- My New Article on Abusive “Schedule A” IP Lawsuits Will Likely Leave You Angry

- If the Word “Emoji” is a Protectable Trademark, What Happens Next?–Emoji GmbH v. Schedule A Defendants

- My Declaration Identifying Emoji Co. GmbH as a Possible Trademark Troll

Pingback: 11th Circuit Sidesteps the SAD Scheme's Problems-Ain Jeem v. Schedule A - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()