In a SAD Scheme Case, Court Rejects Injunction Over “Emoji” Trademark

This is a SAD Scheme case from one of my least-favorite rightsowners, Emojico. (I wrote an expert declaration about them in 2021). Emojico has trademark registrations in the word “emoji” for a ridiculously broad range of product categories–from (I’m not making this up) ship hulls to penis enlargers–and it then licenses the word to product manufacturers and defendants ensnared in its enforcement net. Emojico functionally propertizes a ordinary dictionary word and cashes in. The SAD Scheme helps with that.

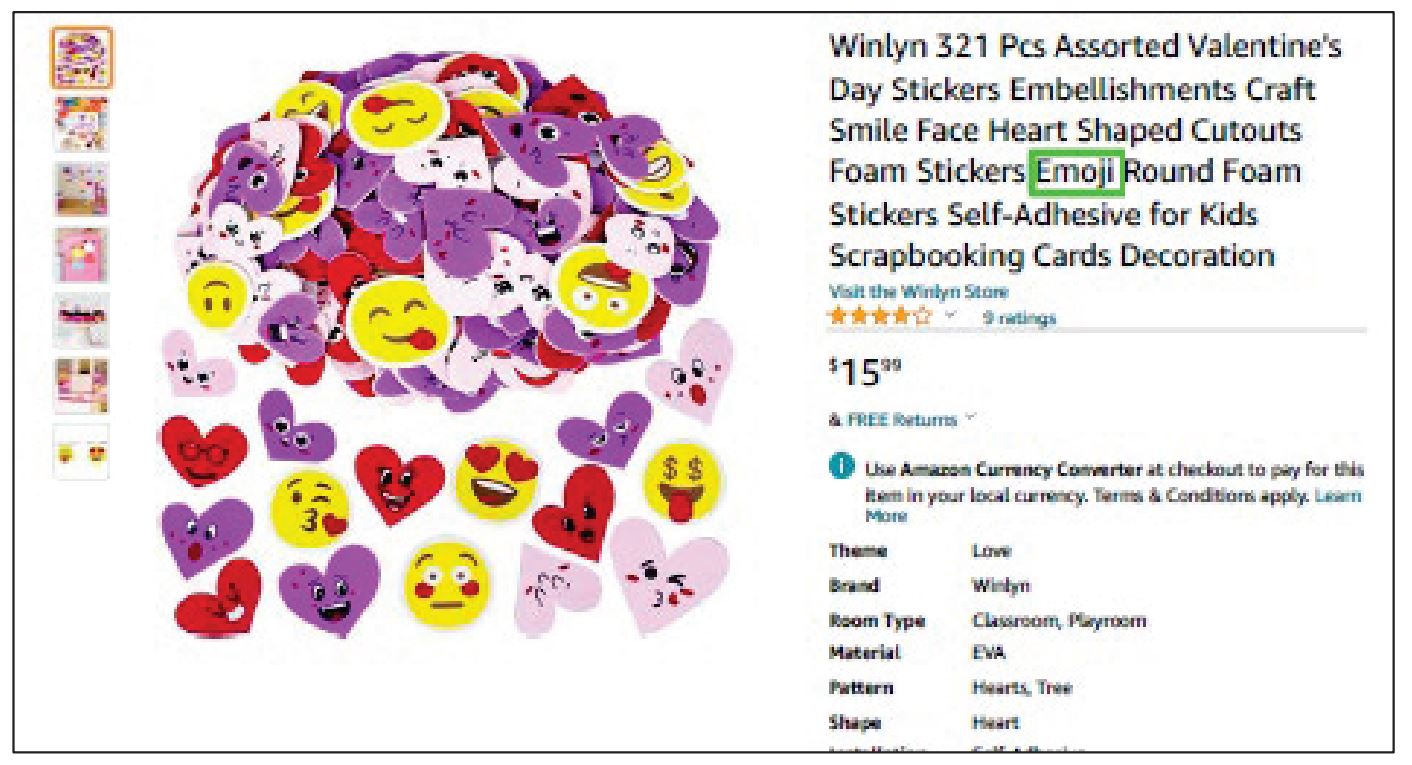

One defendant fought back. The merchant’s Amazon product listing:

I use a nearly identical example in my SAD Scheme paper: an Amazon listing description using the word “emoji” to describe a poop emoji displayed on a mug. I believe Emojico has sued hundreds or thousands of defendants because the word “emoji” appears in the product listing to describe an emoji displayed on the offered item.

I have no doubt that the screenshot above doesn’t constitute trademark infringement. (In my SAD Scheme paper, I characterize the poop emoji mug example as “not a serious trademark claim”). Indeed, in my opinion, asserting trademark infringement claims over dictionary uses of the term “emoji” is objectively unreasonable and should be sanctioned.

Instead, as with hundreds of other Emojico defendants, the judge in this case issued an ex parte restraining order against the merchant, prompting Amazon to freeze the merchant’s account and cash. The merchant fought back, Emojico didn’t dismiss the defendant voluntarily, and the judge actually issued a ruling on the merits–an incredibly rare confluence of circumstances in SAD Scheme cases.

I’m sure you’re surprised to learn that when the judge actually reviewed the matter on a fully informed basis, it didn’t see trademark infringement.

The court says that the merchant made a descriptive “fair use” of the “emoji” term, but the court didn’t actually say that “emoji” qualifies as a descriptive trademark, instead of an arbitrary mark, for stickers. Nevertheless, the court explains its concerns:

The notion that Winlyn has used the word “emoji” on its Amazon page to indicate the source of the goods, rather than to describe the stickers it is selling, is incredibly strained. Winlyn can quite easily show that it used “Emoji” to describe its Valentine’s Day stickers product because the stickers depict an assortment of love-themed and heart-shaped emojis. The word “Emoji” helpfully describes the stickers that Winlyn is selling. Despite Emoji Company’s apparent confidence in the strength of its brand, the reality is that consumers looking to buy emoji-themed stickers are likely to search for the word “emoji.” This is not because they seek any Emoji-Company-branded products (licensed or otherwise). Rather, it is simply because that is the best way to describe stickers using the iconic pictogram styles. Moreover, Winlyn’s use of the word “Emoji” is buried in the middle of its 26-word-long product name, among other words that would obviously be used as descriptors (e.g., “Round,” Heart Shaped,” “Foam Stickers,” “Self-Adhesive,” “Smile Face.”). Winlyn even includes its brand name at the beginning of the title, which, though not dispositive, certainly helps its case….Winlyn will most likely be able to show that its use of the mark was fair and in good faith, the final element of its fair use defense.

(Emojico would very much like to extract payments from every merchant listed on the Amazon search results for “emoji”).

The court should have embraced its first instinct that the merchant didn’t use “emoji” as a mark. The court could have cited two recent Supreme Court cases (Jack Daniels and Abitron) for the proposition that trademark law only applies when parties are using a trademark as a mark, i.e., to identify and distinguish the source of marketplace goods. The merchant in this case, as well as the poop emoji mug merchant, didn’t use the term “emoji” to identify the source of their products. Both merchants used the term (for its dictionary meaning) to describe the product attributes. As the court notes, there wasn’t another good way for this sticker merchant to inform consumers about the emojis displayed on the product without using the term “emoji.” Trademark law does not restrict that usage.

In discussing likelihood of consumer confusion, the court says: “If a defendant is not using the trademarked language as a source indicator (i.e., as a trademark), then that is a strong indicator that it will not confuse a reasonable consumer.” That’s true. However, if there’s no use as a mark, there’s no need to address consumer confusion at all. (Also, if the court already determined descriptive fair use, there was no need to consider consumer confusion either–see KP Permanent Makeup).

As you can see, the court doesn’t really understand trademark law–which means it had no chance of getting the ex parte TRO ruling right. This is the reality of the SAD Scheme cases. Without the defendants’ perspectives, courts will predictably make basic errors.

The court acknowledges as much:

The Court previously found that Emoji Company satisfied its burden, largely due to the absence of any adversarial presentation. But now, based on Winlyn’s motion, the Court finds that Emoji Company is not entitled to continuing preliminary injunctive relief against Winlyn.

This highlights the structural and irreparable problem with the SAD Scheme. When courts make important but erroneous decisions on an ex parte basis, it undermines the rule of law and causes chaos throughout the Internet.

Although the court recognizes that its ex parte TRO ruling was wrong, the court doesn’t excoriate Emojico for its bogus advocacy. Instead, the court orders the merchant to answer the complaint and proceed with the litigation. What??? Emojico cannot win this case, but the merchant must incur more time and expense to reach the now-obvious denouement. (I suspect Emojico will dismiss the defendant to save costs and reduce the risk of a fee-shift).

Worse, the court doesn’t question if it made the same mistake with respect to the dozens or hundreds of other defendants in this lawsuit who already settled or were subject to default judgments. In fact, many of those prior cases likely involved equally unmeritorious trademark claims, but the court didn’t acknowledge the need to rectify any errors it might have made. If the only consequence to Emojico of its wrongful advocacy is that it can’t proceed against one of the dozens or hundreds of defendants it sued in this case, Emojico isn’t likely to reform its behavior.

So you can see why I have mixed emotions about this ruling. Yay for the court vindicating the interests of one Emojico defendant. Boo that this ruling won’t curb further SAD Scheme abuses.

Case Citation: Emoji Co. v. Schedule A Defendants, No. 22-cv-2378 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 29, 2023)

Pingback: Links for Week of October 6, 2023 – Cyberlaw Central()