Does Snapchat’s Speed Filter Cause Car Accidents?–Lemmon v. Snap

Last year, the Ninth Circuit issued a confusing ruling in Lemmon v. Snap, holding that Section 230 did not apply to the plaintiffs’ allegations that Snapchat’s speed filter caused a terrible car accident, irrespective of whether or not the users published the speed filter. This ruling preserved Section 230’s applicability if the claim had been based on publishing images or videos with the speed filter.

Last year, the Ninth Circuit issued a confusing ruling in Lemmon v. Snap, holding that Section 230 did not apply to the plaintiffs’ allegations that Snapchat’s speed filter caused a terrible car accident, irrespective of whether or not the users published the speed filter. This ruling preserved Section 230’s applicability if the claim had been based on publishing images or videos with the speed filter.

At the same time, it opened the door to potential liability for all tools that help content creators make their content, basically suggesting that the tools would be negligently designed in ways that expose the tool authors to liability for personal injuries. At the time, this seemed less troubling for the Internet ecosystem because the Georgia Court of Appeals held that Snapchat had no duty to the plaintiffs for using the speed filter. So it seemed like the 9th Circuit had again sent plaintiffs into a deadend workaround to Section 230. Then, the Georgia Supreme Court reversed that holding, saying that Snapchat may have a duty, which also converted the Lemmon case into a more dangerous case for Snapchat.

On remand from the Ninth Circuit’s Section 230 denial, the Lemmon district court said that it had already determined a duty existed, so the Georgia Supreme Court ruling in the Maynard case didn’t put pressure on that earlier finding. The district court further concludes that Lemmon properly alleged causation, getting the case past Snapchat’s motion to dismiss. The court explains:

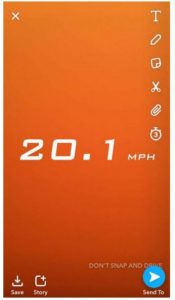

The FAC alleges that the design of the Snapchat app rewards users by awarding trophies for using the Snapchat app in particular ways that are unknown to the users until they actually obtain such trophies. The FAC also alleges that the Speed Filter allows users to record the speed at which they are traveling and display that speed over a photo or video of themselves that they can share on social media. Finally, the FAC alleges that Plaintiffs used the Speed Filter within minutes of the accident.

The Court is satisfied that these three allegations, accepted as true, are sufficient to allege causation premised on the theory that the Speed Filter’s design encouraged Plaintiffs to drive at dangerous speeds. If Snapchat users are seeking to obtain an unknown trophy associated with using the Speed Filter, it is plausible that they would seek this trophy by increasing their speed — the only metric recorded by the Speed Filter.

Even if there were no reward system whatsoever, the basic design of the Speed Filter itself appears to encourage reckless driving. There is realistically no purpose for the Speed Filter other than to encourage users to travel at high speeds and record themselves doing so. Defendant’s argument that users will use the Speed Filter “safely while walking, jogging, or riding a train, boat, or Ferris wheel” is highly implausible…. It is common sense that adding a speed-sharing feature to a social media application used predominantly by minors and young adults would encourage such users to record themselves while driving at high speeds.

The Lemmon court disagrees with the lower court in Maynard v. Snapchat because “it focused on whether the Speed Filter contained an express incentive to speed and ignored the incentives inherent in the Speed Filter’s design.” The Georgia Supreme Court ruling addressed duty, not proximate causation, so it’s inapposite to this ruling.

The Lemmon court distinguishes the Facetime distracted driving cases because the allegation is that the speed filter encouraged speed, not distracted driving, Also, “One of the only realistic uses of the Speed Filter is for users to record themselves traveling at high speeds. It is extremely foreseeable that minors and young adults would use the Speed Filter to record themselves driving at excessive speeds, and even more so if there are potential reward “trophies” for so doing…. The causal connection between the Speed Filter and the speeding accident is strong given that the accident occurred while the Plaintiffs were using the Speed Filter for the exact purpose for which it appears to have been designed: to record the user traveling at excessive speeds.”

I could almost hear the judge asking Snapchat “what were you thinking?” in releasing a speed filter to Snapchat’s youthful audience. Snapchat could take this hint and pursue a settlement. Otherwise, it still has potent defenses it can raise on summary judgment, and of course it can appeal.

Meanwhile, now that a case against an Internet service has worked around Section 230 and survived a motion to dismiss, surely other plaintiffs will be interested in exploring this ground. I bet most plaintiffs will overestimate their odds of success, but a sufficiently lengthy queue of plaintiffs poses its own risks to the ecosystem.

Case citation: Lemmon v. Snap, Inc., CV 19-4504-MWF (C.D. Cal. March 31, 2022)

More Posts on Snapchat’s Speed Filter

- Snapchat May Have a Duty Not to Design Dangerous Software–Maynard v. Snap

- The Ninth Circuit’s Confusing Ruling Over Snapchat’s Speed Filter–Lemmon v. Snap

- Snapchat Isn’t Liable for Its Speed Filter (Even if Section 230 Doesn’t Apply)–Maynard v. Snapchat

- Snapchat’s Speed Filter Protected by Section 230–Lemmon v. Snap

- Snapchat Temporarily Defeats Another Case Over Its Speed Filter–Lemmon v. Snap

- Snapchat’s Speed Filter Not Protected by Section 230–Maynard v. Snapchat

- Section 230 Helps Snapchat Defeat Personal Injury Claim Due to ‘Speed Filter’–Maynard v. McGee