Snapchat May Have a Duty Not to Design Dangerous Software–Maynard v. Snap

The Georgia Supreme Court has issued a troubled, and troubling, opinion in Maynard v. Snap. The opinion will delight law professors who love geeking out about the elements of common law negligence claims. It will also inspire plaintiffs to bring more negligent design claims against Internet services–a looming tsunami of litigation. But this case also raises important free speech issues that get buried in the court’s technical analysis of the negligence elements, and it casts an uncomfortable shadow over all Internet services about their potential liability when criminals inevitably misuse their tools.

The Georgia Supreme Court has issued a troubled, and troubling, opinion in Maynard v. Snap. The opinion will delight law professors who love geeking out about the elements of common law negligence claims. It will also inspire plaintiffs to bring more negligent design claims against Internet services–a looming tsunami of litigation. But this case also raises important free speech issues that get buried in the court’s technical analysis of the negligence elements, and it casts an uncomfortable shadow over all Internet services about their potential liability when criminals inevitably misuse their tools.

The Facts

I’ve blogged this case three times before, in 2017, 2018 and 2020. In my 2018 post, I summarized:

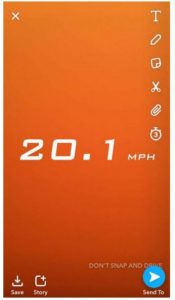

Christal McGee allegedly drove recklessly (over 100 mph) to capture her accomplishment in Snapchat’s speed filter. McGee’s car hit Maynard’s car and caused permanent brain damage to someone in the car. The Maynards sued Snapchat, alleging “Snapchat knew that its users could ‘use its service in a manner that might distract them from obeying traffic or safety laws.’ Further, the Maynards allege that Snapchat’s Speed Filter ‘encourages’ dangerous speeding and that the Speed Filter ‘facilitated McGee’s excessive speeding[,]’ which resulted in the crash.” However, the Maynards do not allege that McGee posted a snap displaying the speed filter.

[An obvious reminder that the speed filter legitimately could be used by passengers to capture their speeds on planes or trains at speeds that would be dangerous or ludicrous if that passenger was driving in a car.]

The lower court initially dismissed the case on 230 grounds. In 2018, the intermediate court reversed. On remand, the lower court dismissed the case again because Snapchat didn’t have a duty that would support the negligence claim. In 2020, the intermediate court affirmed that decision 2-1. In this ruling, the Georgia Supreme Court reverses the intermediate court, saying that the plaintiff properly alleged a duty. That sends this case back to the intermediate court for a third time to consider the motion to dismiss based on proximate causation and perhaps other negligence elements. I wonder if the intermediate court will send that question back to lower court for a third time.

Note: the complaint was filed in April 2016. It’s now been in the courts for 6 years and it’s still at the motion to dismiss stage. Remember that point when we consider the litigation costs of the Georgia Supreme Court’s ruling.

Lemmon v. Snap is a separate, but similar, lawsuit in the California federal courts. That case also involves Snapchat’s speed filter, and the plaintiffs are the parents of boys who died in a car crash after using the filter. I’ve blogged that case three times as well, in Feb. 2020, March 2020, and 2021 (the appellate ruling that made my list of top 10 Section 230 developments of 2021). The lower court dismissed the complaint on Section 230 grounds. The Ninth Circuit reversed, saying that the plaintiffs could plead around Section 230 by alleging defective design. The Georgia Supreme Court ruling likely has implications for the Lemmon case too.

What the Court Said

A common law negligence claim typically has four elements: duty, breach, causation, damages. This highly technical opinion focuses exclusively on the first element of duty; it doesn’t resolve the other elements. Its literal holding is that the intermediate court improperly applied the wrong standards for evaluating duty, and Maynards’ allegations about duty survive a motion to dismiss. Maynards’ complaint may still be insufficient on the other negligence elements, and it leaves open the possibility that the Maynards won’t be able to prove that Snapchat owed them a duty on summary judgment or at trial. So this opinion only partially answers one of several questions that allow the case to proceed, and doesn’t definitively answer any question about whether Snapchat is ultimately liable. Unfortunately, he narrowness of the opinion’s scope increases the odds of misreadings by plaintiff lawyers who are excited about bringing more lawsuits.

On the core question of whether Snapchat owed a duty to the Maynards, the court says manufacturers must “use reasonable care to reduce foreseeable risks of harm from a product when selecting from alternative designs.” In this context:

Maynards adequately alleged at the motion-to-dismiss stage that Snap owed Wentworth a design duty with respect to the particular risk of harm at issue here – namely, injury to a driver resulting from another person’s use of the Speed Filter while driving at excess speed

Furthermore, because Snap allegedly gathered more information about Speed Filter usage over time and could update the software remotely based on that new information, the Maynards could also show that “Snap could reasonably foresee that the product’s design created a risk of car accidents like the one at issue here, triggering a duty for Snap to use reasonable care in designing the product in light of that risk.” Thus, the lead opinion concludes that the Maynards alleged a “conventional design-defect claim.”

The court’s definition of duty–reasonable care, foreseeable risks, selecting among alternatives–has important implications for the costs of litigation, both in terms of discovery and the ability to dismiss an unmeritorious case early. The lead opinion doesn’t care: “the fact that some manufacturers may have to litigate negligent-design claims involving intentional misuse beyond the motion-to-dismiss stage and may ultimately be liable in proportion to their degree of fault does not offend Georgia public policy.” As a bone to defendants, the lead opinion says that “pretrial adjudication – either at the motion-to-dismiss stage or on summary judgment – may be warranted with respect to certain negligent-design claims involving intentional product misuse,” but this should be impossible unless the plaintiff’s counsel is massively overreaching or incompetent.

Three concurring judges feel the lead opinion is too sanguine about the litigation and discovery costs. Counting up the votes, the lead opinion only had 2 votes supporting its cost discussion. 2 judges recused, 2 judges dissented, and 3 concurred with reservations on these points..

But let’s go back to the court’s reference to McGee’s “excess speed.” This is euphemistic; McGee allegedly broke several laws. The court says that’s not dispositive:

a manufacturer may have a design duty, even when an injury is caused by third-party tortious use of a product…Although Snap points to several examples in which the General Assembly has by statute prohibited drivers from engaging in certain dangerous conduct while driving, we see nothing in those statutes suggesting that the General Assembly sought to relieve manufacturers of their own duties with respect to the products they sell, to the extent that they have any duties under the particular circumstances of a case, simply because a driver also breached a duty imposed by law

To accommodate the concerns about McGee’s criminal conduct, the lead opinion says: “the likelihood and nature of a third party’s use of a product may be relevant in determining whether the particular risk of harm from a product was reasonably foreseeable, and thus whether a manufacturer owed a decisional-law design duty to avoid that risk in a particular case.” In other words, whether Snap had to anticipate McGee’s intervening criminality becomes (in practice) another question for trial. Furthermore, “the doctrines of comparative negligence and apportionment operate to limit a manufacturer’s liability to its degree of fault,” but that’s not much help to defendants because this damage adjustment will be made only through trial, and even a small share of a large jury damages award can create a major liability exposure for defendants.

Two dissenting judges believe the intervening criminality is dispositive: “imposing a duty on a manufacturer at the design stage to account for and design against its product being used in the commission of a crime falls beyond what is reasonably foreseeable under traditional principles of tort law…the universe of reasonable uses of an otherwise legal product that a manufacturer must anticipate extends only to those uses that are lawful. When designing a product and considering the risks it poses, a manufacturer is not responsible for contemplating and guarding against the myriad ways the product might be used in the commission of a crime or crimes.”

The lead opinion says the dissent’s concerns are relevant to the proximate causation element, not the duty element. Thus, the lead opinion distinguishes the many car accident cases involving cellphones and texting/Facetiming while driving by saying they all involve proximate cause, not duty. Negligence nerds may care a lot about whether the issue of intervening criminality resides in the duty or causation element of negligence. Here, it lets the court show sympathy for the plaintiffs and opprobrium for “Big Tech,” while quietly shunting off the hardest and most critical issue to other judges.

Implications

There’s much to dislike about the court’s opinion. Its lack of concern about the litigation costs for a case already in court 6 years. Its tendentious parsing of the negligence elements that unhelpfully shifts around where courts consider intervening criminality. Its sidestepping of multiple precedential cases (it uses variations of the term “unpersuasive” six times–a warning indicator of possible judicial activism). However, the part that bugged me the most was the court treating Snapchat’s speed filter as if it were a physical widget. Snapchat helps its users generate speech and engage in social discourse; garden shears and Slip-n-Slides do not. Imposing negligence duties on “manufacturers” of speech-enhancing materials has much broader secondary implications on free speech than imposing those duties on standard chattel. Thus, at minimum, any negligence liability in this case raises potential First Amendment considerations–another thing the court didn’t address.

Finally, the Georgia Supreme Court ruling doesn’t address Section 230 at all. However, because defective design is a pleadaround to Section 230 per the Lemmon v. Snap case, the opinion gives hope to plaintiffs that they can both sidestep Section 230 and have a viable claim. However, if this case does fail on other grounds–such as McGee’s criminal activity–this opinion could be yet another false hope for plaintiffs.

Case citation: Maynard v. Snap, Inc., 2022 WL 779733 (Ga. Sup. Ct. March 15, 2022)