Section 230 Covers Republication of Old Yearbooks–Callahan v. Ancestry

Ancestry.com publishes 450,000 old yearbooks in the form of 730M records that contain, at least, “the person’s name, photograph, school name, yearbook year, and city or town (at the time of the yearbook).” Ancestry doesn’t disclose how it acquires the yearbooks (it does ask for donations, but it’s hard to believe it got 450,000 donations). It sells access to yearbook records about specific individuals. Ancestry markets the records by featuring individuals, with their photos, from the database. The plaintiffs allegedly have individual records in the yearbook databases and were allegedly featured in email marketing. The plaintiffs sued Ancestry for California 3344 publicity rights violations, UCL, intrusion into seclusion, and unjust enrichment.

Ancestry.com publishes 450,000 old yearbooks in the form of 730M records that contain, at least, “the person’s name, photograph, school name, yearbook year, and city or town (at the time of the yearbook).” Ancestry doesn’t disclose how it acquires the yearbooks (it does ask for donations, but it’s hard to believe it got 450,000 donations). It sells access to yearbook records about specific individuals. Ancestry markets the records by featuring individuals, with their photos, from the database. The plaintiffs allegedly have individual records in the yearbook databases and were allegedly featured in email marketing. The plaintiffs sued Ancestry for California 3344 publicity rights violations, UCL, intrusion into seclusion, and unjust enrichment.

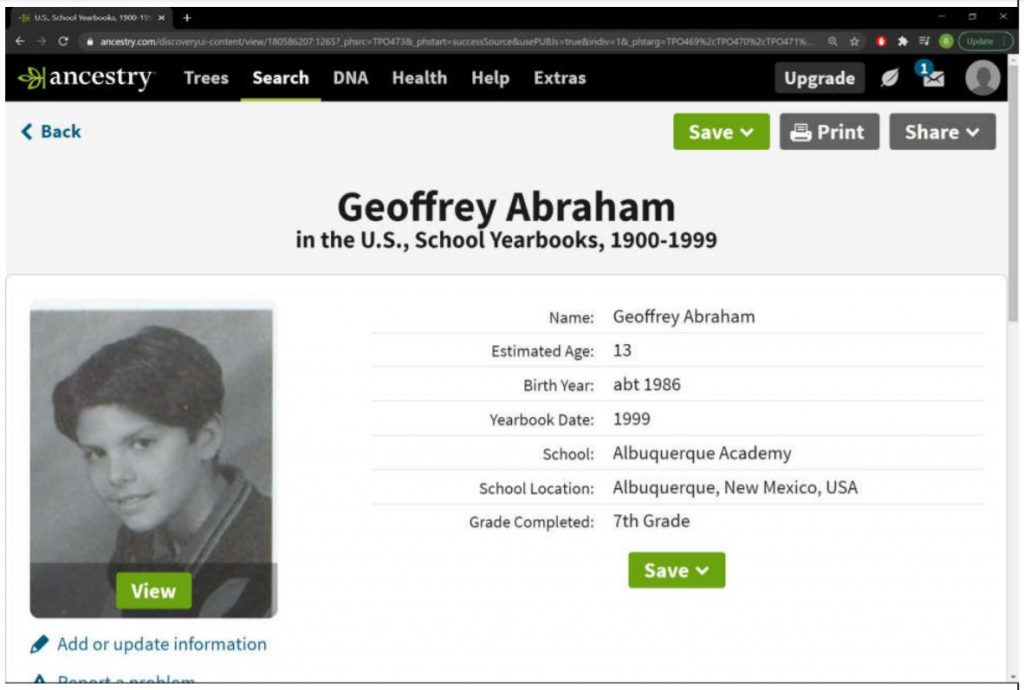

An example of an Ancestry record about one of the plaintiffs:

Article III. The fact that Ancestry commercializes the yearbooks isn’t an Article III harm by itself. (The court quotes the great Judge Grewal line that a “plaintiff must do more than point to the dollars in a defendant’s pocket; he must sufficiently allege that in the process he lost dollars of his own”). The court distinguishes Fraley v. Facebook because “Ancestry’s use of the plaintiffs’ profiles does not imply an endorsement of Ancestry’s products or an equivalent interest.” Unfortunately, the court doesn’t show what an email ad looked like, which would help assess if the ad creates an express or implied endorsement (I didn’t see an example of email marketing in the complaint, either). Instead, the court agrees with Cohen v. Facebook that the plaintiffs “did not show that they had a commercial interest in their images that precluded the platform’s use of them.” Weirdly, the court implies that Article III harms would occur only when plaintiffs have a “commercial interest in their images,” like celebrities, though publicity rights equally apply to all individuals.

The fact that Ancestry allegedly committed a statutory violation (of CA’s publicity rights statute) doesn’t bootstrap into automatic Article III standing because the statute expressly applies only if plaintiffs suffer an injury.

Section 230. Ancestry procured the yearbooks from third parties, so it presumptively qualifies for Section 230. It’s so well-accepted in the Ninth Circuit that Section 230 applies to publicity rights that the court doesn’t even discuss that issue. The plaintiffs argued that it lacked proper consent from the yearbook sources, so that meant it didn’t get the yearbooks from another information content provider. I don’t recall seeing this precise argument made before, and it’s as crazy as it sounds. The court responds plainly: “no case supports the conclusion that § 230(a)(1) immunity applies only if the website operator obtained the third-party content from the original author.” Indeed, I could cite dozens of Section 230 cases where the uploading user clearly wasn’t the original author (my go-to cite in this circumstance is the D’Alonzo case).

Citing Fraley, the plaintiffs also argued that Ancestry lost Section 230 because it “extracts yearbook data (names, photographs, and yearbook date), puts the content on its webpages and in its email solicitations, adds information (such as an estimated birth year and age), and adds interactive buttons (such as a button prompting a user to upgrade to a more expensive subscription).” Citing Kimzey v. Yelp and Coffee v. Google, the court explains:

In contrast to the Fraley transformation of personal likes into endorsements, Ancestry did not transform data and instead offered data in a form — a platform with different functionalities — that did not alter the content. Adding an interactive button and providing access on a different platform do not create content. They just add functionality…

Ancestry — by taking information and photos from the donated yearbooks and republishing them on its website in an altered format — engaged in “a publisher’s traditional editorial functions [that] [] do not transform an individual into a content provider within the meaning of § 230.”

(Another apropos citation might have been Marshall’s Locksmith v. Google).

The court grants Ancestry’s motion to dismiss with leave to amend, but rejected Ancestry’s anti-SLAPP motion because “decades-old yearbooks are not demonstrably an issue of public interest.”

I’m a little surprised the court didn’t discuss Lukis v. Whitepages, which rejected a 230 defense for a database selling “background reports.” That case said Section 230 didn’t apply because Whitepages assembled data from multiple sources, while Ancestry apparently remixed content just from yearbooks. Still, both sold individual records extracted from larger data corpuses, so I would have appreciated a compare/contrast.

Case citation: Callahan v. Ancestry.com Inc., 2021 WL 783524 (N.D. Cal. March 1, 2021). The complaint.

UPDATE: The plaintiff filed an amended complaint and the court dismissed it again, this time with prejudice.

The opinion distinguishes the Lukis precedent by saying it didn’t address standing; and if it did, the Lukis plaintiff alleged financial harm, which this plaintiff didn’t do.

As for Section 230, the plaintiffs cast doubt on the provenance of the yearbooks, but the court says the yearbooks are third-party content, no matter what. The court distinguishes Batzel: “Ancestry of course cannot publish private information that the provider did not intend to be posted online. But here, the information was not private and, whether the yearbooks were donated by other former students or obtained from other sources, Ancestry is demonstrably not the content creator and instead is publishing third-party content provided to it for publication.”

Callahan v. Ancestry.com Inc., 2021 WL 2433893 (N.D. Cal. June 15, 2021)