Section 230 Doesn’t Protect Advertising “Background Reports” on People–Lukis v. Whitepages

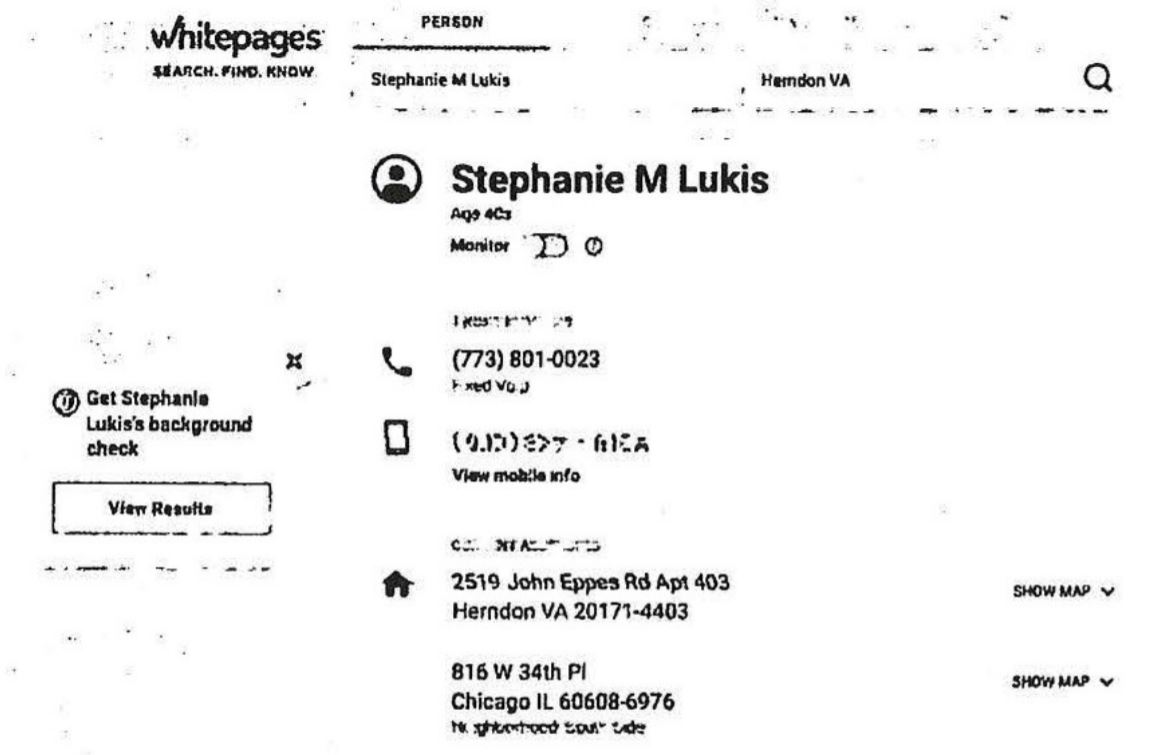

Whitepages compiles and generates “background reports” on people, remixing content from a database of public and private records that allegedly incorporates 2B+ records/month. In response to searches on people’s names, Whitepages provides free previews, such as this one included in the court opinion (this is a truncated view–it goes on for 3 pages):

Much of the free preview provides links indicating that more information about the person may be available behind Whitepages’ “premium” paywall. Thus, the plaintiffs assert that the free preview acts as advertising for the premium service.

Instant Checkmate runs a similar service to Whitepages. The interface is different, but the plaintiffs still characterize the free preview as advertising for the paywalled database.

The plaintiffs claim that the free preview violate Illinois’ publicity rights statute by displaying people’s personal data in the “ads.” The defendants moved to dismiss. This case reminded me a little of the uncited Facebook Sponsored Stories case (Fraley v. Facebook).

Statutory Elements. “The complaint alleges that Whitepages used Lukis’s identity—reflected by her name, age range, and city of domicile, along with the names of some of her relatives—in free previews used to advertise, promote, and offer for sale its monthly subscription services. That is a textbook example under the IRPA of using a person’s identity for a commercial purpose.”

This is a tricky area. Even if the “free previews” advertise the paywall, the previews have standalone substantive editorial value that should be protected by the First Amendment. The court sidesteps this issue, saying “Whitepages used Lukis’s identity to advertise not a background report regarding Lukis, but a monthly subscription service giving the purchaser access to background reports on anybody in Whitepages’s database. Thus, Lukis’s identity was not part and parcel of the entire product or service being advertised.” I kind of understand where the court is going, but overall that doesn’t make any sense. Would the court have dismissed the case if Lukis’ identity were the “entire product”? Alternatively, perhaps this can be easily fixed by Whitepages scaling back to just promoting Lukis’ full report and not its entire database.

The court also punts on the applicability of the statutory exclusion for promotions of books, news, etc. where the publisher makes editorial uses of the protected identity. The court explains:

a report might be protected from IRPA liability if it were limited to information gleaned from judicial records [Nieman v. VersusLaw], but it appears that Defendants’ reports include far more information than that. One might still ask whether Defendants’ reports more like (i) a newspaper or magazine article regarding a person, or (ii) a private investigator’s report on that person. The record does not say, and if the answer is (ii), Defendants do not address whether a private investigator’s report qualifies as a “book,” “article,” “visual … work” under Section 35(b)(1) or as “news” or “public affairs” under Section 35(b)(2). It therefore is impossible to agree, as a matter of law and at this juncture, with Defendants’ submissions that their free previews are protected from liability by Section 35(b)(4).

Section 230. The court might have said that Section 230 doesn’t apply to publicity rights claims as IP claims (which is probably true everywhere except the 9th Circuit), and the court doesn’t address the closely analogous FTC v. Accusearch case denying Section 230 protection for the sale of telephone call records. Instead, citing the terrible 7th Circuit Huon decision, the court says “Whitepages did not act as a mere passive transmitter or publisher of information that was ‘provided by another information content provider.’ Rather, it is alleged to have actively compiled and collated, from several sources, information regarding Lukis. The CDA therefore does not shield Whitepages from liability.”

Like, seriously? Of course Section 230 applies to “active compiling and collating” third-party content. HELLO, GOOGLE SEARCH. Worse, the Huon opinion doesn’t use the terms “compile” or “collate”; the “passive” reference in Huon was only in the plaintiff’s allegations; and the only reference to “active” was to a site operator posting comments in its own forum. Indeed, the Huon opinion rejected the Section 230 defense due to the plaintiff’s not-credible allegation that Gawker had written the allegedly defamatory user comment, which has nothing in common with this case.

So the court in this case misinterpreted the applicable Section 230 precedent and made up a wholly unsupported new Section 230 exception. I’d like to think that kind of error would be fixed on appeal, but the Seventh Circuit’s Section 230 jurisprudence is notoriously unpredictable.

Look, I understand why the judge doesn’t like services like Whitepages or Instant Checkmate. I was dispirited by my limited reviews of their services–at minimum, they have serious data quality problems; and the services enable obvious potential misuse like harassment/stalking or worse. Still, mucking Section 230 and twisting statutory publicity rights factors aren’t the right solutions.

Case citation: Lukis v. Whitepages Inc., 2020 WL 1888916 (N.D. Ill. April 16, 2020)