Website Denied Section 230 for No Good Reason, Wins the Case Anyways–DF Pace v. Baker-White

[Warning: long and sad blog post ahead. Get the tissues now]

This case involves the Plain View Project, run by Injustice Watch. The PVP republishes social media posts by law enforcement officers that might signal racist, misogynist, or other discriminatory attitudes. To gather the posts, the “Defendants” (the court isn’t more specific here) reviewed the social media accounts of 3,500 law enforcement officials and screenshotted 5,000 questionable posts. The posts are searchable by officer name, rank, badge number, and jurisdiction. The site’s homepage explains the goal:

We present these posts and comments because we believe that they could undermine public trust and confidence in our police. In our view, people who are subject to decisions made by law enforcement may fairly question whether these online statements about race, religion, ethnicity and the acceptability of violent policing—among other topics—inform officers’ on-the-job behaviors and choices.

To be clear, our concern is not whether these posts and comments are protected by the First Amendment. Rather, we believe that because fairness, equal treatment, and integrity are essential to the legitimacy of policing, these posts and comments should be part of a national dialogue about police.

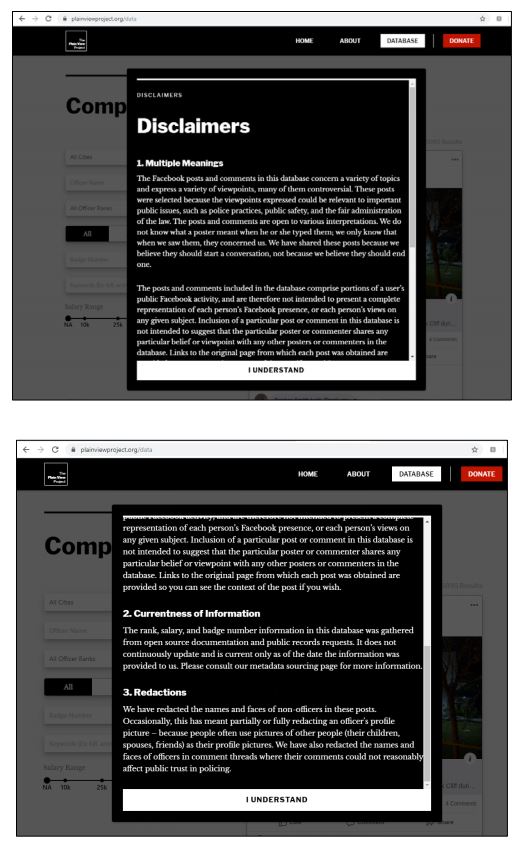

Anyone accessing the database had to click through this “disclaimer”:

The Facebook posts and comments in this database concern a variety of topics and express a variety of viewpoints, many of them controversial. These posts were selected because the viewpoints expressed could be relevant to important public issues, such as police practices, public safety, and the fair administration of the law. The posts and comments are open to various interpretations. We do not know what a poster meant when he or she typed them; we only know that when we saw them, they concerned us. We have shared these posts because we believe they should start a conversation, not because we believe they should end one.. . .

Inclusion of a particular post or comment in this database is not intended to suggest that the particular poster or commenter shares any particular belief or viewpoint with any other poster or commenters in the database. . . .

Readers could not miss the disclaimer:

This case relates to the following Facebook thread:

If you can’t read the original post by Philadelphia police officer Anthony Pfettscher, it said: “I’m cracking up at that America college student that [sic] went to North Korea and tried to steal a poster. He is crying and pleading like a little baby girl because he was just sentenced to 15 years hard labor. Although my heart breaks for his family, it’s an eye opener to how spoiled and coddled our youth of today are here in this weak PC country. Yet they act like animals and burn and step on our Flag that [sic] so many of our children died for defending our rights and our country. #SeeYouIn15Years #WakeUpAmerica #AskWhatYouCanDoForYOURcountry.”

The plaintiff, D.F. Pace, commented in response: “Insightful point.” He sued Injustice Watch for defamation and false light, arguing that his inclusion in the database–combined with the site’s explanations–makes it look like he condones bad police behavior. Injustice Watch moved for a 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss.

Section 230

Attempting to describe the background jurisprudence, the judge taxonomized Section 230 cases into a continuum with the following nodes:

- “cases in which an interactive computer provider merely hosts or republishes defamatory content.” Section 230 applies.

- “cases which feature defendants curating information, including selecting what gets posted or excluded.” The court cites Reit v. Yelp, where Yelp won on Section 230 in the face of allegations it “had selectively removed positive reviews of his practice but left negative ones.”

- “other cases address positioning or increasing the prominence of allegedly defamatory content.” The court cites Asia Economics v. Xcentric and Small Justice v. Xcentric as cases where Section 230 protected the enhanced prominence.

- “In some cases, defendants engage in editing or make editorial judgments, which triggers arguments about what constitutes content editing versus content creation.” This node looks a little rocky, because everything else above also involves “making editorial judgments.” Still, the court cites Dimeo v. Max and Blumenthal v. Drudge, both of which upheld Section 230 defenses.

- “Other cases involve defendants who added their own commentary to third-party statements, but the plaintiffs only alleged the third-party statements were defamatory, not the defendants’ commentary.” Cites to Jones v. Dirty World, Marfione v. KAI, and Shiamili v. Real Estate Group. Again, all Section 230 defense wins.

So far all of the identified nodes and cited Section 230 defense wins. This looks like another easy win, right?

The court describes the final node:

- “At the far end of the continuum, content creators and developers are not entitled to Section 230 immunity.” Cites to Roommates.com, Huon v. Denton, and FTC v. Accusearch.

No arguments here–this literally restates the statute–so I guess I can’t quibble too much with the court’s taxonomy, even if I didn’t find it very enlightening. But then the court throws us for a huge loop.

The court says this case is distinguishable from many other cases because “Plaintiff is seeking to hold Defendants liable for what the Defendants’ own words—when read in conjunction with a non-defamatory statement he made on Facebook—imply about him.” Thus, the court says this “case does not fall neatly into any of the aforementioned categories along the continuum….Give [sic] the distinctive nature of this case, the Court returns to the text of the statute to analyze the facts here.”

Seriously, WTF? Why did the court build this not-particularly-useful taxonomy over the course of 4 pages–simply to toss it aside?

Claiming just to analyze the statutory text allows the court to untether itself from about 1,000 precedent cases, which is a recipe for malicious judicial activism (recall the Daniel v. Armslist appellate court decision, which did the same thing to reach a terrible and clearly reversible outcome). Thus, this “statutory analysis” move lets the court go crazy.

The court says the defendants “created” the content at issue:

although Defendants published Plaintiff’s words on the PVP, they readily acknowledge that they provided the words on the introductory pages of the PVP website—a framing narrative through the website’s homepage, disclaimer, and “About” tab….In adding the framing narrative, Defendants did much more than merely “packaging and contextualizing[,]” structuring a website layout, increasing content’s prominence, or selecting what to publish….

The defamatory implication arises, according to Plaintiff, from its framing by the introductory text created by Defendants. One could conclude from that Defendants created that content “in whole.” Even so, to extent that one could conclude that, absent Plaintiff’s words, there could be no defamation by implication, and that as such Defendants were not the sole author of the allegedly defamatory statements, they nevertheless are responsible for it in part.

Ugh. No. Make it stop. What the court is trying to say is that the plaintiff’s post was not defamatory in isolation (how could it be–it was literally the plaintiff’s words), but the defendant replanted the original post into a new context that added an allegedly defamatory meaning to the post. I’m not sure such context-repotting should avoid Section 230; but if there is such a workaround, it needs tight and nuanced definition. Unfortunately, the court instead tried to shoehorn this case into the “content creation” exception of Section 230, which just opens up lots of questions about the philosophical and practical meanings of the term “create.” This case would have better fitted into the Roommates.com standard when a defendant adds illegality to otherwise-legal third party content. Here, the allegation is that the defendant added the defamation through its contextualization. As much as I hate the Roommates.com case, that would have been a much better analytical tool than this court’s “statutory analysis” of the word “create.”

Having ripped open a wound in Section 230 jurisprudence, the court proceeds to pour salt into that wound by saying the defendants are “responsible” for the content they “created.” I have no words. Instead, I’ll just quote the whole thing. While you’re reading it, I’ll be crying my eyes out (extra tissues at the right):

Having ripped open a wound in Section 230 jurisprudence, the court proceeds to pour salt into that wound by saying the defendants are “responsible” for the content they “created.” I have no words. Instead, I’ll just quote the whole thing. While you’re reading it, I’ll be crying my eyes out (extra tissues at the right):

In focusing on whether Defendants are “responsible” for the framing content on the PVP website, dictionary definitions once again lead to the conclusion that they are. To be responsible for a harm is to be “accountable for one’s actions” or to be “the cause or originator of something; deserving of credit or blame for something.” See Oxford English Dictionary Online, www.oed.com/view/Entry/163863 (last visited Jan. 8, 2020). Thus, to be responsible for offensive content, “one must be more than a neutral conduit.” Accusearch, 570 F.3d at 1199. “That is, one is not ‘responsible’ for the development of offensive content if one’s conduct was neutral with respect to the offensiveness of the content (as would be the case with the typical Internet bulletin board). We would not ordinarily say that one who builds a highway is ‘responsible’ for the use of that highway by a fleeing bank robber, even though the culprit’s escape was facilitated by the availability of the highway.” Id. Thus, “a service provider is ‘responsible’ for the development of offensive content only if it in some way specifically encourages development of what is offensive about the content.” Id. Such a construction of the term “responsible”—requiring more than neutral conduct or the mere providing of a platform—satisfies the CDA’s purpose, which is to encourage the flow of information online by protecting Internet services from liability when third-parties use the services to post harmful content. See 47 U.S.C. § 230(a)-(c).

Here, the PVP website was not a “typical Internet bulletin board[,]” neutrally facilitating the sharing of harmful content. See Accusearch, 570 F.3d at 1199. It was “much more than a passive transmitter.” See Roommates, 521 F.3d at 1166. Defendants created the introductory narrative on the PVP website thereby making a material contribution to the creation of the allegedly defamatory content, and are therefore “responsible . . . for the creation or development of information” at the core of this lawsuit. See 47 U.S.C. § 230(f)(3). Accordingly, they are not entitled to Section 230 immunity

This is wrong in 1,000 ways. Rather than work through my pain on the blog, I will just mourn silently instead.

Interestingly, the court didn’t discuss a glaring issue: the screenshots weren’t submitted to the defendants. Instead, they gathered the screenshots on their own, raising the question of whether the screenshots should have been characterized as content from “another information content provider.” On the plus side, this would have sidestepped the court’s “create” and “responsible” statutory misinterpretation. On the minus side, this still points towards a defense win. Section 230 applies to cut-and-paste jobs of third party content per the uncited case D’Alonzo v. Truscello (also from a Philadelphia court).

Meanwhile, the court ignored the many cases where Section 230 has, in fact, applied to the defendant’s own words. See, e.g., Milo v. Martin. The “Ripoff Report” and “PissedConsumer” cases are also highly relevant here, because both of those sites ensure a negative context for the third-party reviews. The court was clearly aware of the Ripoff Report cases, but obviously thought those cases were distinguishable/ignorable.

Defamation

My sadness turned into uncontrollable sobbing heaves when I realized the court didn’t even need to analyze Section 230 at all. The court concludes that any defamatory implication added by the defendants is non-actionable opinion because the site disclaimer had sufficient hedging words. Thus:

the implications that Plaintiff belongs to a set of current and former police officers who endorse violence, racism, and bigotry and act in manners consistent with these biases in their official capacity; that Plaintiff endorses violence, racism, and bigotry; that Plaintiff is not carrying out his oath of office with integrity; that Plaintiff acts in a manner that undermines trust in police; and that he does not treat people equally are not capable of defamatory meaning. They are statements of opinion by Defendants that readers could view Plaintiff in that way—leaving open the possibility that they also could not.

Beating the dead horse, the court further says that the plaintiff didn’t sufficiently plead the required malice. The plaintiff is a police inspector and department leader, which the court treats as a public figure.

As a result, because the defendants didn’t defame the plaintiff, the court dismissed the case with prejudice.

What Does It Mean?

Let’s get this out of the way. I think the court’s entire Section 230 discussion is dicta. The taxonomy/continuum, built only to be tossed aside, is double-dicta (dicta to the dicta). Please don’t cite it.

This ruling is actually worse than dicta. The court makes a categorical error of allowing allegations of illegality to plead around Section 230, even though there actually isn’t any illegality. In other words, the defendant needs Section 230’s immunity only when third-party statements are, in fact, defamatory; but the court concludes there never was any defamatory content, so Section 230 isn’t needed. The Roommates.com en banc majority made exactly the same mistake: it said Roommates.com didn’t qualify for Section 230 because it allegedly had illegal content, only to conclude 4 years later that there had never been illegal content on Roommates.com (and thus Roommates.com should have qualified for Section 230 all along). Read this way, the two parts of the court’s opinion don’t cohere with each other. If the court had flipped the order of its discussion, then it wouldn’t have discussed Section 230 at all because there was no tortious content requiring immunity.

If other courts consider the Section 230 discussion when they shouldn’t, the court’s Section 230 discussion implies that defamation plaintiffs can plead around Section 230 by claiming that the defendant’s context surrounding third-party content added defamatory import. This argument usually won’t work, but it will increase adjudication costs. Terrible.

Finally, we should note that the PVP website addresses an critical issue in our society: some taxpayer-funded employees charged with upholding our laws may hold discriminatory views that affect how they do their jobs. Social media has provided a new, and extremely troubling, window of insight into this problem. We need sites like PVP to highlight the problem, and we need increased vigilance to remove law enforcement officers who in fact do not follow the law when doing their jobs.

Case Citation: D.F. Pace v. Baker-White, 2020 WL 134316 (E.D. Pa. Jan. 13, 2020)

Pingback: News of the Week; January 15, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall()