Twitter Defamation Claim Defeated by a Question Mark–Boulger v. Woods

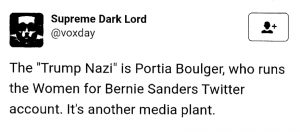

This is a defamation lawsuit brought against James Woods by a woman (Portia Boulger) who was wrongly identified as a Nazi supporter online. In March, candidate Trump had a rally in Chicago. The Tribune posted a photo of a woman at the rally giving the Nazi salute. The next day “@voxday” posted the photograph, along with a photograph of plaintiff identifying plaintiff as “Organizer (Women for Bernie).”

This is a defamation lawsuit brought against James Woods by a woman (Portia Boulger) who was wrongly identified as a Nazi supporter online. In March, candidate Trump had a rally in Chicago. The Tribune posted a photo of a woman at the rally giving the Nazi salute. The next day “@voxday” posted the photograph, along with a photograph of plaintiff identifying plaintiff as “Organizer (Women for Bernie).”

Woods followed up Voxday’s tweet with the one below:

The woman in at the rally was later identified as “Birgitt Peterseon”. Woods tweeted a correction, although he did not delete his original tweet.

Boulger sued Woods in District Court in Ohio. Woods filed an answer, a motion for judgment on the pleadings, and after the time for service had expired, a motion for summary judgment or for dismissal for failure to perfect service.

The court first says that Woods waived his defense of insufficient process and lack of personal jurisdiction by not raising in his motion for judgment on the pleadings. The court’s discussion is probably of interest to Rule 12 geeks, but I’ll spare the rest of us.

Moving on to the merits, the court says that the key question is whether Woods’s tweet constitutes a statement of fact. Ohio courts employ a totality of circumstances analysis where the author is charged with knowing the perspective of the reasonable reader. The court says that the question mark is decisive:

Were it not for the question mark at the end of the text, this would be an easy case. Woods phrased his tweet in an uncommon syntactical structure for a question in English by making what would otherwise be a declarative statement and placing a question mark at the end. Delete the question mark, and the reader is left with an ambiguous statement of fact . . . But the question mark cannot be ignored.

The court says “inquiry itself . . . is not accusation”. That is not to say that a question will automatically insulate the author. But the court says the First Amendment requires the author to receive the benefit of any plausible innocent interpretation. (Interestingly, the court footnotes and rejects an argument that the term “Nazi” is “not actionable as a matter of law”. The court distinguishes the tweet here in that someone is being accused of literally being a Nazi.)

The court also says that the context matters. However, the court struggles with whether readers should automatically be charged with reviewing Woods’s other tweets during this time-period, or his tweets generally. The court says that a reader would not review an entire twitter account in chronological order. In some situations, authors flag that they are making a series of tweets (“1/x”—a tweetstorm!) but typically a reader is exposed to a “changing, disjointed series of brief messages on multiple topics by multiple authors.” Ultimately the court says that context is not determinative and the court can’t reach any conclusions regarding it. However, at least some of the readers could interpret the tweet as not being a declarative statement of fact. This further points in the direction of the tweet not being actionable.

The court also dismisses the invasion of privacy claim on similar grounds.

__

It’s ironic that Woods, who himself sued a twitter user over being called a “cocaine addict” by an anonymous and hyperbolic twitter user, benefited from the context rule. Background on Woods’s lawsuit from Popehat and Eriq Gardner.

We’ve blogged a bunch about courts’ treatment of defamation claims premised on online content. Twitter in particular lends itself to a medium where people understand statements to include rhetoric and hyperbole. This case brought to mind Feld v. Conway, where the court said that calling someone “fucking crazy” in a tweet was not actionable.

Twitter defamation cases are fascinating, simply because of the nature of the medium itself. Woods could have used the Retweet button. He could have also used an emoji. 🤔

Case citation: Boulger v. Woods, 2:17-cv-186 (S.D. Oh. Jan. 24 2018)

Related posts:

Twibel Ruling: Tweeting That Someone is “Fucking Crazy” is Not Defamatory

Hyperlinking to Sources Can Help Defeat Defamation Claims–Adelson v. Harris

Using Links as Citations Helps Gizmodo Defeat a Defamation Claim–Redmond v. Gawker Media

Want To Avoid Defaming Someone Online? Link To Your Sources (Forbes Cross-Post)

Calling Out Scraper for “Stealing” Data Is Not Defamatory – Tamburo v. Dworkin

A Twitter Exception for Defamation?

9th Circuit Issues a Blogger-Friendly First Amendment Opinion–Obsidian Finance v. Cox