Facebook Gets Bad Ruling In Face-Scanning Privacy Case–In re Facebook Biometric Information Privacy Litigation

The plaintiffs allege Facebook’s face-scanning functionality (that underlies its “tag suggestion” feature) violates the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act. Several lawsuits were originally filed in Illinois, but the parties agreed to transfer the cases to the Northern District of California, where they were consolidated into a single action. Facebook moved to dismiss the lawsuit on the merits and based on the terms of service’s choice of law provision, which said California law governed (since California does not have a biometric privacy act, this would mean plaintiffs could not maintain their claims).

Facebook’s Motion to Dismiss: On the merits, the court declines to dismiss, following the course of another case against Shutterfly. (See “Shutterfly Can’t Shake Face-Scanning Privacy Lawsuit” (blog post on the trial court ruling in that case).) The court says that digital representations plausibly constitute “face geometry” and rejects Facebook’s argument that the statute excludes photographs and information gleaned from them. The court does some fancy footwork with admittedly awkward statutory language, and says that “photographs” as used in the statute refer to “paper prints of photographs”.

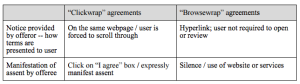

Facebook’s Choice of Law Argument: Facebook’s choice of law argument took up the bulk of the court’s attention, and it actually conducted an evidentiary hearing prior to ruling (based on a summary judgment standard) that Facebook properly formed a contract with all of the plaintiffs. The court goes through the now-familiar clickwrap versus browsewrap spectrum of agreements, even helpfully attaching a chart. (It’s almost as if they read Eric’s comments about avoiding this nomenclature and include this in the discussion to raise his hackles!).

Facebook’s Choice of Law Argument: Facebook’s choice of law argument took up the bulk of the court’s attention, and it actually conducted an evidentiary hearing prior to ruling (based on a summary judgment standard) that Facebook properly formed a contract with all of the plaintiffs. The court goes through the now-familiar clickwrap versus browsewrap spectrum of agreements, even helpfully attaching a chart. (It’s almost as if they read Eric’s comments about avoiding this nomenclature and include this in the discussion to raise his hackles!).

After ultimately concluding that Facebook has an enforceable agreement with all plaintiffs, and this agreement contains a choice of law clause mandating California law for all claims arising out of the Facebook relationship, the court drops the bomb:

“[t]he contractual choice of law will not be enforced”

Ouch. Applying section 187 of the Restatement, the court says that the case presents “strong reasons to depart from the parties’ contractual choice of law.” The main reason is that California does not have a counterpart to the biometric privacy law, and thus enforcing the clause would thwart Illinois’ interest in protecting the privacy of its citizens.

__

This ruling illustrates the continuing importance of online contracting principles. Any lawyers or business folks interested in online contracting would benefit from reading pages 8 through 14 of the court’s ruling (subject to a few caveats below). I recently blogged about a case where flimsy evidence of the online contract doomed efforts to enforce it, but Facebook does not fall prey to that. Still, the changes in the process and the ambiguity of the “sign up” button at one point in the process were interesting to note. (I agree with Eric’s comments below about the court’s handling of the online contracting analysis–it started strong but ended disappointingly.)

The choice of law ruling is a bombshell. Facebook rightly notes that it is a problem for technology companies to not be able to rely on choice of law provisions in their agreements, but the court is not persuaded by this. Choice of law clauses in online terms are extraordinarily difficult for plaintiffs to challenge, and the court was sold by the total absence of a similar regulatory scheme under California law. (I wonder if companies may raise a dormant commerce clause challenge down the road; in the spam context where some states enacted recipient-protective laws, these challenges were not very successful.)

The court’s discussion on the issue of whether information derived from photographs is covered exposes imprecisions in the statutory drafting. If you’re going to go out on a limb and draft a piece of legislation of this nature, you should make sure the language is reasonably precise! Still, credit goes to Illinois legislators. I am guessing Eric will say that this is a piece of misguided legislation that is the latest sparkly object in the eyes of plaintiffs’ lawyers, and will not benefit consumers. But it may also slow down companies’ efforts to build databases, or make them think twice.

Eric’s Comments: The first–and most venerable–rule of legislating technology, especially emerging technology: don’t ban technology, ban bad uses. Legislators have no idea where technological developments will go, so banning technology prevents unknown socially beneficial evolutions. Unfortunately. this statute fails that basic rule, and now we’re seeing the predictable denouement of an outmoded regulation of technology.

[UPDATE: Jay Edelson tweeted: “BIPA “ban[s] technology”? Big stretch, even for @ericgoldman. BIPA is about consent; doesn’t prohibit biometrics.” Except…there may be no practical way of obtaining consent from people depicted in the photos, such as when the depicted individuals aren’t users of the service, are deceased, etc. Where consent isn’t realistically obtainable, a consent requirement acts as a de facto ban.]

[UPDATE 2: Jay Edelson further tweeted, I believe sardonically: “We claim it’s hard to get consent for some people, thus Facebook doesn’t have to get consent from anyone?” Maybe I’m missing something, but the Illinois statute only requires Facebook to get consent from Illinois residents. However, Facebook doesn’t have a magic way to determine the residency of every person depicted in photos. Thus, I think the law does become all-or-nothing, i.e., Facebook must get consent from everyone in the world on the off-chance they are Illinois residents, or the law doesn’t apply. The first scenario neatly frames the Dormant Commerce Clause problem discussed below.]

As Venkat suggests, the Dormant Commerce Clause casts a long shadow on this case. To the extent Facebook can’t technologically identify who is an Illinois resident compared with, say, a California resident, the court’s ruling means that the Illinois statute will affect interactions wholly within California between a California company and California residents. That’s a clear no-can-do under the Dormant Commerce Clause.

I understand the court’s concern about choice-of-law. Internet companies should not be able to override state law by contract when there’s a significant state policy interest in protecting state residents. That’s why I see this as a Dormant Commerce Clause problem, not a contract problem.

Regarding the contract formation, the court starts off strongly by citing the Nguyen v. Barnes and Noble case for the proposition: “To determine whether a binding contract has been formed, the dispositive questions are (1) did the offeror “provide reasonable notice” of the proposed terms, and (2) did the offeree “unambiguously manifest assent” to them?” Then everything goes to shit when the court says “To answer those questions for contracts formed on the Internet, our Circuit has settled on an analytical framework that puts “clickwrap” agreements at one end of the enforceability spectrum and “browsewrap” agreements at the other.”

As usual, the court can’t figure out where Facebook’s user agreement belongs on this chimeral clickwrap-browsewrap spectrum, saying that the agreement has some browsewrap aspects (because the terms were actually linked, not presented in full on the page) and some clickwrap aspects (because there was an affirmative check on a statement like “I have read and agreed to…”). When your test can’t tell where to place the Facebook agreement, which is obviously a clickthrough agreement AND IT’S NOT EVEN CLOSE, your test sucks and you probably should scrap it in favor of a better test. Maybe like this test: “the dispositive questions are (1) did the offeror “provide reasonable notice” of the proposed terms, and (2) did the offeree “unambiguously manifest assent” to them?” Sigh.

Facebook did get a very favorable ruling on the efficacy of its amendment process. The court said the users got actual notice of the amendments through direct email and “jewel notification” (the red number on the blue line at the top of Facebook’s screen). [Jargon watch: this is the first use of the term “jewel notification” to describe Facebook’s red-on-blue scheme that I found in Westlaw’s database. FWIW, a Google search for “jewel notification” found only about 250 hits]. Citing Rodman v. Safeway, the court concludes: “This individualized notice in combination with a user’s continued use is enough for notice and assent.” Most online sites don’t do as much notification of amended terms as Facebook did and instead rely on the BS assertion that they can post amended terms to the site and that automatically binds future uses. They should take note of what worked!

Finally, try to read this sentence without laughing: “‘Photographs’ is better understood to mean paper prints of photographs, not digitized images stored as a computer file and uploaded to the Internet.” Digital photo exceptionalism FTW!

Case citation: In re Facebook Biometric Information Privacy Litigation, 2016 WL 2593853 (ND Cal. May 5, 2016)

Related posts:

Shutterfly Can’t Shake Face-Scanning Privacy Lawsuit

Disney Not Liable For Disclosing Device IDs And Viewing Habits

App Users Aren’t “Subscribers” Under the VPPA–Ellis v. Cartoon Network

Ninth Circuit Rejects Video Privacy Protection Act Claims Against Sony

AARP Defeats Lawsuit for Sharing Information With Facebook and Adobe

9th Circuit Rejects VPPA Claims Against Netflix For Intra-Household Disclosures

Lawsuit Fails Over Ridesharing Service’s Disclosures To Its Analytics Service–Garcia v. Zimride

Minors’ Privacy Claims Against Viacom and Google Over Disclosure of Video Viewing Habits Dismissed

Is Sacramento The World’s Capital of Internet Privacy Regulation? (Forbes Cross-Post)

Hulu Unable to Shake Video Privacy Protection Act Claims

California Assembly Hearing, “Balancing Privacy and Opportunity in the Internet Age,” SCU, Dec. 12

It’s Illegal For Offline Retailers To Collect Email Addresses–Capp v. Nordstrom