Section 230 Doesn’t Apply to “Editorializing” About Third-Party Content–Marvin v. Lanctot

This case involves the Warroad High School girls’ hockey team. Warroad, Minnesota is located just a few miles south of the Canadian border, near the Northwest Angle, and hockey appears to be a big thing in town (e.g., the town calls itself Hockeytown USA).

On October 30, 2023, a group of community members circulated a letter that seemingly accused head coach Marvin of player mistreatment and other misdeeds. Marvin sued a number of community members for their involvement with the letter, claiming defamation. The ruling I’m blogging today involves Kristin Coauette Johnson, whose relationship with the team is unspecified (she appears to be a hockey mom?).

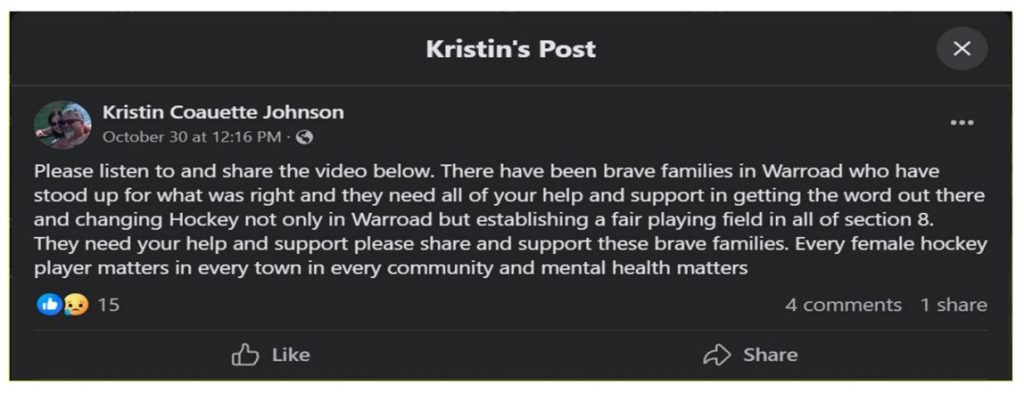

Coauette made two public postings regarding the October 30 letter. First, on October 30, she made this Facebook post that linked to an interview by the Grand Forks Best Source discussing the letter:

(I couldn’t find this post on Facebook, so I assume it’s been taken down. The screenshot comes from the opinion).

Second, Coauette made another Facebook post on October 31 that displayed the letter with an introduction authored by Coauette saying “What a brave parent group to come forward”:

The court doesn’t make this clear, but the October 31 post appears to be Coauette sharing Lanctot’s third-party post to a FB group “We Hear You 56763.” (56763 is the zip code covering Warroad, MN).

* * *

With respect to Coauette’s liability for defamation, the court frames the issue as whether “Section 230 supersedes the common law republication doctrine with respect to statements made on the Internet. This issue is a matter of first impression in Minnesota.”

With respect to Coauette’s liability for defamation, the court frames the issue as whether “Section 230 supersedes the common law republication doctrine with respect to statements made on the Internet. This issue is a matter of first impression in Minnesota.”

(The claim that 230’s application to defamation hasn’t been litigated before in Minnesota really surprised me, but I wasn’t able to disprove it quickly).

The court distinguishes Barrett v. Rosenthal and Banaian v. Bascom because the defendants in those cases didn’t add their own commentary to the third-party content. Thus, the court reframes the issue as whether “Section 230 also immunizes someone who reposts with comments or editorializes the attached information.”

Reframed this way, the answer is easy. The defendant might be liable for the words they added. However, they may not be held liable for the third-party content they share, promote, or amplify.

Unfortunately, the court doesn’t reach this simple conclusion. Instead, the court says Coauette “arguably endorsed the attached content” and “included commentary that both supported the original content provider and provided additional assertions.” The court notes that the Sixth Circuit’s Jones case expressly rejected an “adoption or ratification” workaround to Section 230, yet the court is influenced by the La Liberte v. Reid and Pace v. Baker-White cases. (Recall I wrote a “long and sad” blog post on the Pace case).

This leads to the court’s conclusion that Section 230 doesn’t apply:

it is apparent from Coauette’s posts that she felt she was informing the community of an important issue by reposting the October 30 Letter and the podcast. Her comments with the letter and the linked podcast qualify as an endorsement…Coauette encouraged the public to listen to and share the interview. Coauette advocated for individuals to “help and support” the cause….Coauette’s added commentary is a material contribution to the original content

This is obviously the wrong conclusion. The court does not suggest that any of the words Coauette actually typed are defamatory, and I don’t see how those words could support a defamation case. As a result, Coauette’s potential liability appears to be solely based on third-party content she references/linked to. The “material contribution” test is supposed to apply only when the defendant adds the alleged illegality to the third-party content, such as taking a third party’s non-defamatory statement and making it defamatory. Coauette clearly didn’t do that.

So, the court disqualifies Coauette from Section 230 for “endorsing,” amplifying, and expressing sympathy for, allegedly defamatory third-party content. Section 230 clearly covers all of those activities; otherwise, it would be trivially easy to route around 230 in every case. I see this case as analogous to the email forwarding cases (Phan v. Pham is quite on point), the linking cases (Milo v. Martin is also quite analogous), and the retweeting/quote tweeting cases, where the quote-tweeting liability comes solely from any added words, not the fact that the third-party tweet is being amplified or endorsed. See, e.g., US Dominion v. Byrne; Coomer v. DJT for President.

As a result of the court’s obvious legal error, I hope this conclusion is appealed, because it’s a good candidate for reversal.

Case citation: Marvin v. Lanctot, 68-CV-23-682 (Minn. Dist. Ct. May 17, 2024). The complaint.

UPDATE: Bui v. Ky, 320 Cal.Rptr.3d 788 (Cal. App. Ct. May 8, 2024): “What is in the record is a declaration by Ngo conveying the Facebook post contained certain pictures and a video. Plaintiff’s defamation claim is not grounded in those depictions. Rather, it is aimed at extrapolations about plaintiff made by defendants after viewing the photos and video. As the creators of the alleged defamatory content, defendants fall outside the protections of section 230.“