An E-Commerce Site Tried to Form Its TOS Three Different Ways. None of Them Worked–Chabolla v. ClassPass

The plaintiffs claim they signed up for a ClassPass membership but got unexpectedly auto-renewed. (ClassPass appears to be an aggregator of third-party fitness classes). ClassPass sought to send the case to arbitration based on its TOS, which it attempted to form in each of the following three screenshots:

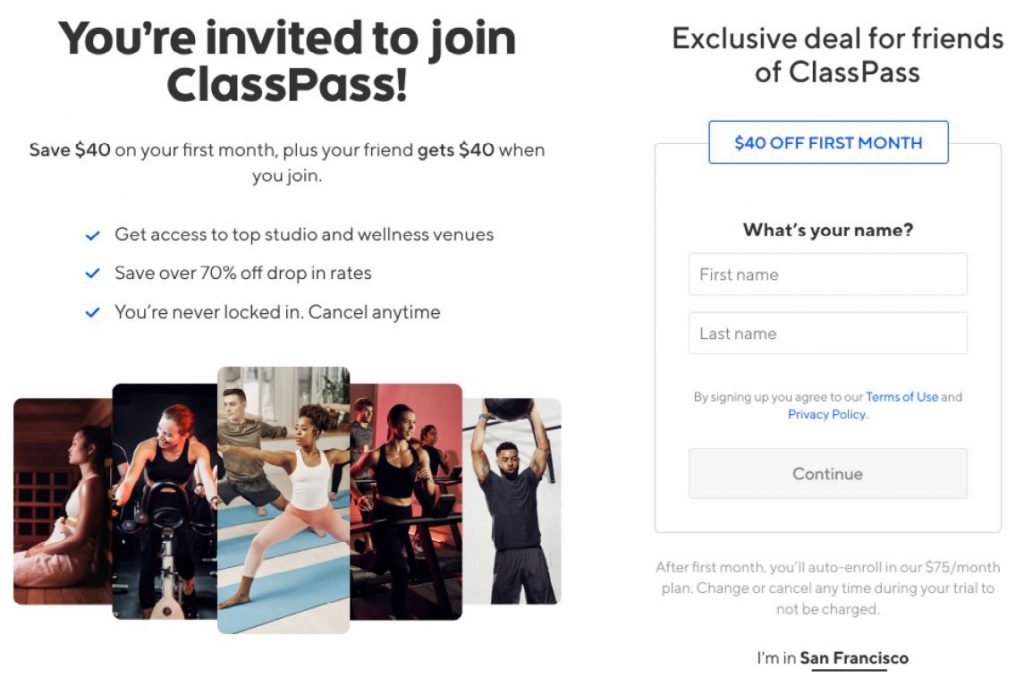

Screenshot #1

Screenshot #2

Screenshot #3

With three different attempts, surely one of them worked, right? Citing extensively to Berman and JustAnswer, the court says no. What went wrong???

The court classifies the three formation screens as sign-in-wraps because “(i) it contains textual notices of the Terms; (ii) the Terms are hyperlinked but not incorporated into the webflow; and (iii) prospective members are not required to affirmatively indicate that they have reviewed the Terms prior to registering for a membership.” The court then analyzes if consumers manifested assent to these terms:

Reasonably Conspicuous Notice. The court said the calls-to-action are all in light grey text with blue fonts for the links, while the surrounding text is larger and much darker. (Practice reminder: your call-to-action should never be the smallest or faintest text on the screen).

In a footnote, the court adds: “the Court is not persuaded that internet users of average technological sophistication would automatically understand blue font to indicate the existence of a hyperlink, especially where, as here, the font is not underlined, and the text notice is not phrased to clarify to a user that they could access the Terms and Privacy Policy by clicking the blue phrases.” OK boomer. Citation needed. In my Internet Law courses, my Gen Z students intuitively understand that contrasting blue text in a call-to-action is a hyperlink, even without underlining.

The court says: “Additionally, the text notice containing the hyperlinks appears directly below the “Sign up with Facebook” button and further afield from the “Continue” button, which renders the visual connection between the notice and “Continue” button less clear.” To be fair, the call-to-action in screenshot #1 expressly conditions its efficacy on the “Continue” button, which many judges would consider sufficient make the necessary cognitive link even if the button and call-to-action are not directly adjacent.

The court also objects to the overall page layouts:

The text notices appear in the bottom righthand side of the first two pages in the sign-up webflow, whereas the bulk of those pages is taken up by photos of individuals exercising and far larger text touting the benefits of ClassPass and their trial membership offering. On the last of the three signup webpages, legal copy abounds, with some text appearing on the left-hand side of the page underneath high-level explanations of the trial membership. Whereas this final page bolds certain important information about the trial membership, for instance, that prospective members can “Cancel anytime” and that they will be provided “1 month (and 45 credits) to book any classes [they] want,” no such bolding is applied to the text notice linking to the Terms and Privacy Policy. The cumulative effect of these textual and organizational design choices is to de-emphasize references to the Terms and Privacy Policy, rendering them inconspicuous.

This emphasize on the sales pitch in the early screens is hardly surprising or unusual. These screenshots are sales pages. The judge’s remarks could easily apply to many “sign-in-wrap” formation screens.

Manifest Assent. The court rejects the calls-to-action in screenshots #2 and #3. In screenshot #2, the court says that the reference to “signing up” is ambiguous because it could mean “clicking the ‘Continue’ button on that webpage, completing the signup webflow, or something else.” This seems like a tendentious interpretation. It could have been clearer, but I bet many consumers would have intuitively understood “signing up” to refer to the membership. In screenshot #3, the phrase “I agree to the Terms and Privacy Policy” isn’t expressly linked to any action, so the court disregards it. Again, this could have been clearer, but the court could have just as easily implied that moving forward in the process was the implied predicate.

Having rejected the calls-to-action (or lack thereof) in screenshots #2 and #3, only screenshot #1 remains in play. It’s still not good enough to the court: “the Court is not persuaded this text and the accompanying button, viewed in the context of the transaction between Ms. Chabolla and ClassPass, create circumstances in which prospective members unambiguously manifest their assent to the Terms.”

The court says that in the context of an auto-renewal membership, “the first webpage in the sign-up webflow is noticeably sparse on details and offers no indication that by completing the page a prospective member has created an account or effectuated a monetary transaction.” This includes disclosures about price, but also, in screenshot #1 prospective customers haven’t submitted anything other than their email address. Furthermore, screenshot #1 doesn’t refer to creating an account; it just asks for an email address. Thus,

the first page in the sign-up webflow would be more accurately characterized as “preliminary marketing material,” as compared to text with a clear contractual purpose…

a reasonable internet user visiting the page would not intend, by simply entering their email and seeking to learn more about the membership offer they had been advertised, to have entered into a contractual relationship with ClassPass at that juncture

Notice how the court’s piecemeal analysis of ClassPass’ webflow divides-and-conquers. ClassPass can legitimately say that it makes stronger sales pitches on screenshots #2 and #3, but the court disregarded the cumulative educative effects of the screenshots in sequence. It also shows how close ClassPass likely was to proper formation; if it had simply used the proper call-to-action on the third screenshot, the prior screenshots’ teachings would have counted.

Implications

The court clearly approached the vendor’s formation process with extreme skepticism. Maybe that was an (over?)correction to the anti-consumer consequences if this case went to arbitration. It’s not clear to me that other judges will grade contract formation as harshly as this judge did.

And yet…ClassPass could have avoided the judge’s skepticism and tendentiousness simply by adding one additional click requiring consumers to assent to the terms, which would have led to a “clickwrap” classification and near-certain enforcement. Thus, the ruling reiterates my standard advice nowadays: don’t get cute with one-click formation processes. Skip the second click, and you take your chances.

ClassPass has already appealed this ruling to the Ninth Circuit. Perhaps we will get better insights there.

Case Citation: Chabolla v. ClassPass Inc., 2023 WL 4544598 (N.D. Cal. June 22, 2023). The complaint.