Contractual Control over Information Goods after ML Genius v. Google (Guest Blog Post)

by guest blogger Prof. Guy Rub, The Ohio State University Michael E. Moritz College of Law

The copyright – contract tension

Stewart Brand famously said that information wants to be free. We know, however, that many laws limit free access and use of information goods, most prominently copyright law (and IP law generally). But copyright law isn’t limitless; it leaves many intangible goods, especially factual data, unprotected, and it allows many uses of protected works.

Nevertheless, at least in theory, other laws can fill the gaps in copyright’s limited propertization of information goods. The flexibility of contracts makes them a prime candidate for restricting uses that copyright law leaves unprohibited. This tension between copyright policy and contract law is not new, but developments within and outside the law might put it center stage again.

Some built-in limitations within contract law prevent it from effectively limiting some forms of data usage. The remedies under contract law, for example, are significantly more modest than those under copyright law, and they might not effectively deter some usages. Moreover, because liability under contract law depends on proving privity, it, unlike copyright law, cannot bind third parties. Last but certainly not least, contract law does not include secondary liability doctrines like copyright law, which places liability on those who assist or facilitate violations by others. As a result, I argued elsewhere, contract law might be effective in allowing one company to restrict the use of information by another company, particularly a competitor. It is, however, somewhat less valuable in creating a mass scheme that de facto limits the activities of many small users.

That still leaves a rather broad space for contract law to effectively limit the use of information. Yet contracts might — just might — be subject to additional restrictions, including from outside of contract law. Specifically, those who allegedly breached contracts over information goods can (and often do) argue that the contract is expressly preempted by section 301(a) of the Copyright Act. That section states that rights under state laws that are “equivalent” to rights under copyright law are preempted.

ML Genius v. Google

The last major decision applying section 301(a) to a breach of contract claim was delivered by the Second Circuit in 2022 in ML Genius v. Google. While this is an unpublished opinion, it is a rather important one, both for the development of the law and because it deals with the abilities of websites to exercise control over their contents and the abilities of others to scrape and use that information.

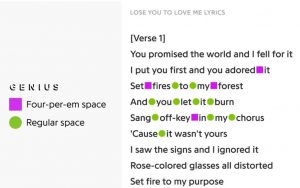

The core facts of the case are rather simple. Genius.com is a leading website for lyrics, which it collects from artists and users. In the last few years, however, when users search for lyrics of popular songs on Google, an “information box” (also known as a Google Knowledge Graph) with those lyrics appears before the search results, answering many users’ questions without leaving Google. This is great for Google but highly harmful to Genius, which, like many websites, bases its business model on users’ traffic and advertisements. Genius planted tiny mistakes in some of the lyrics it posted, and once those appeared in Google’s information boxes, it argued that Google copied lyrics from Genius. Both parties, Genius and Google, are, of course, not the copyright owners of those lyrics but only non-exclusive licensees, making a copyright claim unavailable to Genius. Genius’s “browsewrap,” however, prohibits copying for commercial use, and Genius sued Google for breach of contract.

The core facts of the case are rather simple. Genius.com is a leading website for lyrics, which it collects from artists and users. In the last few years, however, when users search for lyrics of popular songs on Google, an “information box” (also known as a Google Knowledge Graph) with those lyrics appears before the search results, answering many users’ questions without leaving Google. This is great for Google but highly harmful to Genius, which, like many websites, bases its business model on users’ traffic and advertisements. Genius planted tiny mistakes in some of the lyrics it posted, and once those appeared in Google’s information boxes, it argued that Google copied lyrics from Genius. Both parties, Genius and Google, are, of course, not the copyright owners of those lyrics but only non-exclusive licensees, making a copyright claim unavailable to Genius. Genius’s “browsewrap,” however, prohibits copying for commercial use, and Genius sued Google for breach of contract.

Google argued that the contract was preempted by Section 301(a) of the Copyright Act as equivalent to copyright, and the Second Circuit agreed. Relying on an approach previously articulated by the Sixth Circuit, it held that because “the promise in a contract amounts only to a promise to refrain from reproducing, performing, distributing or displaying the work, then the contract claim is preempted.”

There are more than 300 opinions by federal courts dealing with the express preemption of contracts, and within them two main approaches have emerged. The first approach, the majority approach, suggests that because contracts create bilateral rights between the parties while copyright is a property right against the world, contracts cannot be equivalent to copyright and are therefore never preempted by section 301(a). This approach is mostly identified with the 1996 Seventh Circuit decision in ProCD v. Zeidenberg, although it was also adopted by the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits, as well as the Federal Circuit (in a case applying the First Circuit’s law). The minority approach suggests that preemption depends on the content of the contract. If the contract limits any action that copyright law restricts, meaning reproduction, distribution, adaptation, or public performance or display of works within the scope of copyright, it is preempted. Until recently, the Sixth Circuit was the most prominent court that endorsed this approach.

Before 2019, the Second Circuit did not express its opinion on this question (although it decided cases dealing with contractual control over unprotected data), but then, almost in passing, it held a contract preempted. In Genius, the Second Circuit continued this trend and fully embraced the Sixth Circuit’s minority approach. While this is only the second appellate circuit to adopt this approach, the Second Circuit, having jurisdiction over New York State, hears a disproportionally high number of cases concerning copyright and contracts. In other words, the approach taken by the Second Circuit matters a lot.

The case law in the Ninth Circuit — the other appellate circuit central to developing copyright law, especially regarding new technologies — seems to support the Seventh Circuit’s majority approach. However, it was sometimes not as clear as the case law of other circuits.

A third approach? The Solicitor General’s Brief

After losing at the Second Circuit, Genius asked the Supreme Court to hear its appeal. In December 2022, the Supreme Court invited the U.S. Solicitor General to file a brief on Genius’s petition, and in May 2023, she did so.

The Solicitor General (“SG”) recommended denying the cert petition, but its reasoning was somewhat surprising. The brief notes that the Second Circuit approach is overbroad. That makes perfect sense. Contracts are used quite routinely to restrict the reproduction and distribution of information goods —every non-disclosure provision in any contract does precisely that —so that cannot be the main criterion for preemption. But the SG did not endorse the Seventh Circuit’s approach either or offer a comprehensive test of its own to decide the degree to which contracts can regulate the use of information goods.

Instead, the SG argued that the case is not a good vehicle for addressing this question, primarily because the alleged contract was a “browsewrap”—allegedly formed merely by using a website and not by taking another more explicit action to signal acceptance. This weak form of acceptance, the SG suggested, makes a browsewrap fundamentally different from other contracts (including other standard-form agreements), which should make the preemption analysis unique.

On June 26, just before the end of its term, the Supreme Court denied Genius’s cert petition, putting this litigation to rest. This leaves us with a rather deep split of authorities. On the one hand, some circuits completely shield contracts from preemption. Other circuits, notably the Second Circuit, hold contracts regulating the reproduction and distribution of information goods preempted. The SG’s approach, if courts adopt it, presumably holds browsewrap contracts preempted (and maybe other contracts too; the SG refrained from taking a position on those).

Why does it matter?

One may ask: Should we really care where users find lyrics to their favorite songs? Maybe not, but in a broader context, we really should pay attention to cases like ML Genius v. Google and the issues involved.

First, the dispute touches on the relations between Google and the World Wide Web. In particular, it deals with Google’s alleged attempts in recent years to keep users within its ecosystem. Indeed, while some aspects of Genius’s case made it quite unique — licensees, after all, rarely sue each other for copying — from a broader perspective, Genius is a website that tries to prevent others, especially Google, from copying information that IP law allows Google to copy. There are probably hundreds of popular websites (and apps) that primarily consist of information for which they don’t have copyright: websites focusing on users’ reviews, the weather, sporting results, statistics, governmental information, and more. Google’s information boxes, which arguably discourage users from leaving, can significantly undermine those websites’ incomes and endanger their continued viability (and, in the long run, might undercut the availability of that information). This topic, and Google’s use of its dominant position, found its way to Congressional deliberations, where Google was accused of “intercept[ing] traffic from third-party websites by forcibly scraping their content and placing it directly on Google’s own site.” To a degree, it also mirrors the difficult question concerning the platforms’ impact (and maybe that of the Internet itself) on the news and the organizations that report it.

Second, zooming out further, the case revolves around a topic covered on this blog routinely: data scraping. A matter that is likely to receive even more attention going forward with the increased importance of generative AI. From this perspective, Genius’s complaint is rather standard. Many owners of popular websites — the owners of Facebook, LinkedIn, American Airlines, Ticketmaster, and even Craigslist are a few examples — sued companies who scraped and copied their posted information for breach of their standard form agreements. Just earlier this month, Twitter threatened to sue Meta over its new service, Threads, alleging, among others, that Meta might have scraped Twitter’s data in violation of its terms of service.

Many of those contractual anti-scraping lawsuits were successful. LinkedIn, for example, famously fought hiQ over mining its profiles. The Ninth Circuit, in a much-celebrated opinion, rejected LinkedIn CFAA’s claim, stressing the public nature of the information that was scraped. But a few months later, in a much less high-profile decision, the Northern District of California ruled that hiQ likely breached LinkedIn’s terms and conditions, which led to a settlement agreement in which LinkedIn presumably received everything it wanted.

It is somewhat doubtful that similar results would have been reached if LinkedIn and similar cases were litigated within the Second Circuit jurisdiction. We can try and distinguish between anti-scraping cases based, for example, on the underlying interests they try to protect: some platforms, like Facebook and LinkedIn, arguably tried to protect their users’ privacy and experience, a few airlines likely tried to prevent effective comparisons of prices and benefits, and Genius tried to prevent Google from diverting users’ traffic. However, this is not the focus of the Second Circuit’s approach. That court focuses on the actions that the contract restricts. From that perspective, all those cases seem very similar: plaintiffs asking to enforce form agreements prohibiting mass copying of their websites’ published data. Genius’s browsewrap is likely not the only contract that should be preempted under the Second Circuit’s test. Except, of course, that preemption was not raised as a defense in other recent cases. And it would likely have failed because the Ninth Circuit seems quite hostile to such preemption claims. The Second Circuit’s new case law may, however, eventually cause defendants in California to raise this defense, which might cause the Ninth Circuit to revisit the issue (and maybe, finally, to even come up with a clearer rule).

The SG’s approach is also somewhat tricky. Some of the contracts in the recent anti-scraping cases were browsewraps. American Airlines’ complaint is a good example. Others were probably not. For example, it seems that hiQ expressly accepted LinkedIn’s standard-form agreement. However, in many cases, the exact form of the contract received little attention during the litigation. Maybe after the SG’s brief, parties will pay more attention to the form of the contract in question, although I find it somewhat less likely. While the SG brief paints all browsewrap breach claims as unique, questionable, atypical, and (at least implicitly) uncommon, I’m not sure that’s an accurate description of the online reality.

Moreover, legally, it seems somewhat well established that a browsewrap can be enforceable if its existence is clear enough to a reasonable user or if the defendant actually knew that using the website is conditioned on accepting such terms. Most websites’ terms and conditions can probably meet this low threshold. In fact, Google never argued that it was unaware of Genius’s browsewrap (which makes sense considering the many letters it received from Genius). I’d therefore find it somewhat peculiar if courts start to preempt websites’ browsewrap terms and conditions that pass the test for acceptance under contract law.

Concluding thoughts: In search of a new framework

We started by asking if (and when) contracts can fill the gaps that copyright law leaves and restricts certain uses of information beyond copyright law’s limitations. If express preemption is the way to approach this question, as practically the entire case law suggests, the answer is “it depends.” Not so much on the facts of the case, but mostly on where it is being litigated.

But I doubt that express preemption is the right prism to evaluate contracts over information goods. Express preemption simply asks the wrong question: is a contract equivalent to copyright? This is a rather weird inquiry, which can explain the messy answers that courts (and the SG) provide. The relevant question should be whether or not certain contractual limitations over information goods are socially desirable. In other words, what level of contractual control over public domain information is acceptable.

Other legal tools can address this difficult question more directly. For example, specific statutes can tackle it. The European Union, for example, prohibits certain contractual limitations on reverse engineering. Many legal systems include a host of doctrines to scrutinize all standard form agreements closely, and such doctrines can also be used for contracts over information goods. American courts, however, are generally much more willing to accept and enforce standard form agreements.

However, even in the United States, other ways exist to scrutinize contracts over information goods. One tool that, unfortunately, so far has received very little attention in the case law is implied conflict preemption. This general doctrine holds that state laws cannot “stand[] as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress.” In my opinion, that is a good starting place for developing a more flexible and sophisticated approach to scrutinizing contracts. Maybe the chaos concerning the conflicting approaches in applying the express preemption doctrine, which was only made worse after Genius v. Google, will push some litigators and some courts to move away from it altogether toward a newer and better framework.