2021 Emoji Law Year-in-Review

A recap of emoji law developments in 2021:

Court References

I maintain a dataset of US court opinions that reference emojis and emoticons. I have compiled the dataset using keyword alerts in Westlaw and Lexis, supplemented by a few opinions I’ve found other ways. The latest version enumerates a total of 586 opinions through the end of 2021. Most case references are merely that–the court simply notes the presence of a symbol as part of reciting evidence in the case. Courts rarely display the symbols in their opinions; it happened in less than 10% of the 2021 opinions I indexed.

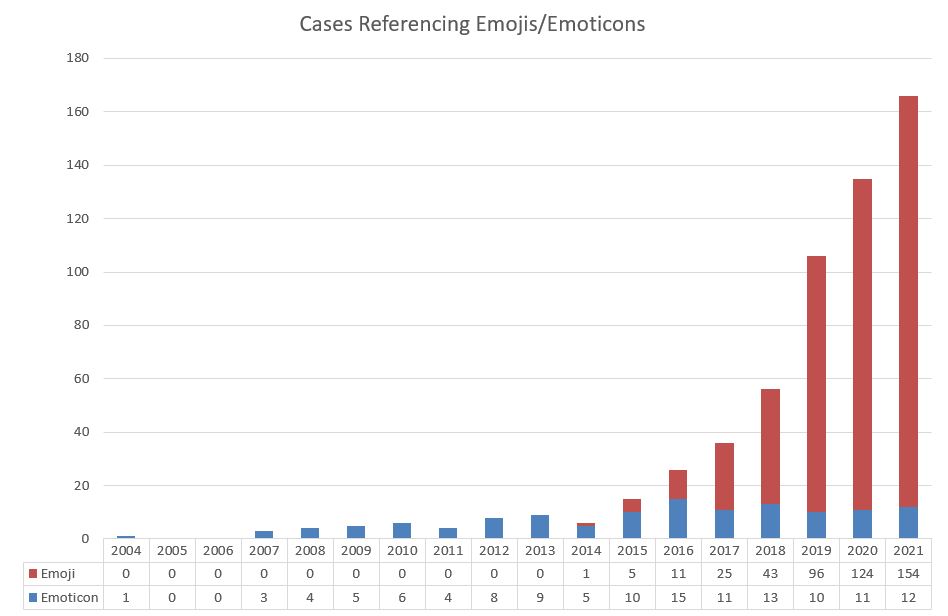

The chart below depicts the number of cases by year, further divided by references to emoticons or emojis [FN]. As you can see, court references to emojis and emoticons continue to grow at an exponential rate. I found 166 cases in 2021 (so far), a 23% increase over 2020.

[Footnote: courts sometimes clearly mislabel the symbol. Furthermore, where an opinion references both emojis and emoticons, I counted those only in the emoji category. There are many other caveats to the emoji/emoticon breakdown and the dataset generally–ask me if you want more details. The bottom line is to treat the dataset as a directional indicator, not as a quantitatively precise report.]

As you can see, emoticon references peaked in 2016, and the number has roughly stayed steady since then (but see the footnote above). In contrast, emoji references have skyrocketed since then, a sign of their ever-growing adoption.

Breaking down the 2021 cases by underlying subject matter:

- “Sexual predation” (both solicitations of minors by adults and actual sexual abuse): 21 cases

- Employment discrimination: 19

- Murder: 9 (this is a noticeable increase from past years)

Breaking down the 2021 cases by mode of communication:

- Text messages: 61 (this is a noticeable increase from past years)

- Facebook/Instagram: 35

- Email: 17

Some of the emoji symbols that I believe had their debut court reference in 2021: Belorussian Flag, “boxing,” camera, dinner plate (a sexual euphemism, but I’m still not sure what it stands for), frog, ghost, nails being painted, package, peanuts, pig, and wheelchair.

Other Top Developments

Emoji variations expose fabricated evidence. Easily the most significant emoji law ruling of the year. A plaintiff presented evidence that she claimed was from her iPhone 5 (which can only run up to iOS10), but actual emoji symbol depicted in the evidence was only available on iOS13 or higher. The court says simply: “This image is a fabrication.” Kudos to the defense team for their strong emoji forensics work.

Copyright Review Board ruling on emoji copyrightability. Individual emoji symbols can obtain copyright registrations… sometimes. When exactly? When the symbols “include something in addition to common tropes and shapes,” and even then, the registrations should only preclude verbatim copying.

Emoji Co. GmbH. I wrote an expert opinion characterizing Emoji Co. GmbH as potentially a trademark troll due to their high litigation volume and dubious litigation tactics. Two hotspots: ex parte proceedings provide far too many gaming opportunities for plaintiffs, and sealed lists of dozens of defendants should be a huge red flag.

Emojis in the US Supreme Court. I believe the word “emoji” made its first Supreme Court appearance in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., the “Fuck school fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything” case. The student’s message included an upside-down smile emoji, which the opinion referenced but did not show. Note that the Elonis case involved an emoticon, but the Supreme Court opinion didn’t reference it.

Courts still denigrate emoji evidence. In Dean v. REM Staffing, 1:20-cv-00235 (N.D. Ill. May 10, 2021), the district court recounted how an email saying “Yes, I accept. Dear [smiley]” formed a settlement agreement. The 7th Circuit affirmed the decision, but its opinion recaps the email as saying “Yes, I accept”–leaving out the “dear” and the smiley, even though those components could have flipped the message’s meaning.

My Emoji Law Year-in-Review for 2020.