Are Individual Emoji Depictions Copyrightable? Yes…Well, Sometimes…It Depends…

Though it might surprise you, copyright can protect individual emoji depictions. However, determining when they are copyrightable is a subtle art. This summer, the Copyright Review Board issued an interesting decision about the registrability of emojis. Though it won’t be the final word on the topic, the decision gives us more insights into the Copyright Office’s thinking on the matter.

[Note: you may not have heard of the Copyright Review Board before. It’s so obscure that the board doesn’t have its own page on the Copyright Office website describing its work (indeed, I couldn’t find a single mention of it on Copyright.gov). I don’t normally track the board’s decisions.

The Copyright Review Board is the Copyright Office’s internal administrative review process for the registration decisions of individual copyright examiners. It’s composed of three Copyright Office officials, including the Register of Copyrights. It has issued 33 decisions so far in 2021. That relatively low volume helps explain why its decisions can fly under the radar. Copyright Review Board decisions are appealable in federal court as an administrative agency ruling.]

The Board’s Decision

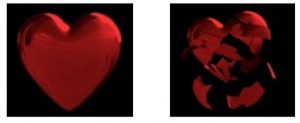

The case involves 10 different heart emojis that are animated for 1-3 seconds (the screengrabs on the right depict the heart “breaking in pieces”). The examiner denied the registrations. The Copyright Office explained that “each animation is composed of uncopyrightable common and familiar shapes, ‘such as circles, semicircles, hearts, ovals, or minor variations thereof….each sequence is comprised of only one or two movements with minor linear or spatial variations.'” Apple appealed to the Copyright Review Board. The board issues a split decision: 4 emojis aren’t registrable; 6 are. Distinguishing the two groups helps define the copyrightability frontier.

The case involves 10 different heart emojis that are animated for 1-3 seconds (the screengrabs on the right depict the heart “breaking in pieces”). The examiner denied the registrations. The Copyright Office explained that “each animation is composed of uncopyrightable common and familiar shapes, ‘such as circles, semicircles, hearts, ovals, or minor variations thereof….each sequence is comprised of only one or two movements with minor linear or spatial variations.'” Apple appealed to the Copyright Review Board. The board issues a split decision: 4 emojis aren’t registrable; 6 are. Distinguishing the two groups helps define the copyrightability frontier.

The board says the unregistrable emoji animations “include a familiar heart design and some very minimal amount of motion, which is de minimis and thus unprotectable by U.S. copyright law. The red color adds to the familiar and predictable nature of the heart designs. Additionally, the metallic texture on the hearts is a basic effect that is common in graphic design.” This applies to:

- the beating heart, a 2-second video depicting the heart beating rhythmically

- the jumping heart, a 3-second animation with 2 simple jump motions

- the sparkling heart, a 1-second animation with “repeated depiction of four-point stars at various locations around a red heart”

- the arrow-pierced heart, a 1-second animation that’s “a ‘garden-variety’ depiction of a common trope”

Apple argued that the animations comprise dozens of individual images. The board responds: “It is not the numerosity of images, however, that determines copyrightability. One hundred images of a simple, unadorned circle, for example, would not be protected by copyright simply due to quantity.”

The six registrable emoji animations “all include something in addition to common tropes and shapes….the heart also transforms into an uncommon design or presents additional shapes using a series of sequential images that convey the illusion of motion.” Also, all 6 “include different light sources to give the animated shapes dimension and shadows that shift as the shapes perform various movements.” Some details about each:

- the breaking-in-half heart depicts “a heart shivering upward then splitting in half. The split begins in the middle of the heart and then travels downward along an unsymmetrical path. As the heart breaks, it tilts to the right. This is not a common animation or design”

- the breaking-in-pieces heart and breaking-into-smaller-hearts depictions “transform from complete hearts into differently shaped shards of heart pieces or differently shaped hearts. The different types of hearts and pieces are notable in their animation”

- the spinning heart and streaming heart “include a large heart that slowly moves upward and downward as several smaller hearts circle around, or float from, the large heart. This arrangement and use of certain numbers of hearts meets copyright law’s low threshold for protection”

- the heart-with-wings includes “a creative depiction of a pair of flapping wings. Each wing includes detailed drawings of feathers in various sizes and shapes”

The board cautions Apple that “the resulting protection is thin and applies only to the overall works and not to a heart design in general.”

Implications

The board’s language makes it possible to distinguish between the registered and rejected emoji animations: there needs to be one unusual or unexpected element to the heart depiction to demonstrate the necessary minimal spark of creativity and thereby clear the originality standard. Still, reading the board’s opinion, the line-drawing exercise feels a little like the Copyright Office knows it when it sees it. Thus, when the board says the arrow-pierced heart is a “common trope,” but the breaking-in-pieces/breaking-into-smaller-hearts are “notable” in their animation, it’s not providing a lot of guidance to predict the next case. (And don’t lose sight of the implicit cultural biases and DEI risks associated when characterizing something as a “trope” or “notable.” Who sets the baseline, and how representative are they?).

To be clear, I’m not criticizing the board’s conclusion. The board starts with the premise that even incredibly simple works are presumptively copyrightable. From there, at the frontiers of copyrightability, the legal questions are always hard. The exact nuances of the border will always feel a little arbitrary.

The board’s determination applies to animated emojis; the board didn’t address unanimated individual emoji depictions. When I’ve spoken about emoji IP before, I’ve indicated that animated emojis would be treated like (very) short videos for copyrightability purposes. As the board implies, if a photograph is copyrightable, a short video of the same subject material should qualify as well. Thus, animojis, memojis, AR emojis, and other variants of animated emojis are all presumptively copyrightable. However, when a user’s facial expressions or body movements are used to animate the emoji, it leaves open the obvious question about who owns the copyright(s) to the resulting animation, including whether there could be overlapping blocking copyrights or joint ownership.

As for unanimated emoji depictions, this opinion reinforces that some emojis won’t qualify for copyright protection. For example, if their animated counterparts aren’t copyrightable, then static emojis depicting a standard red heart, even if it has a sparkle or an arrow piercing it, probably can’t be registered either. However, more detailed emoji depictions that aren’t “garden variety” illustrations of “common tropes” could still be copyrightable. The Copyright Office has issued thousands of copyright registrations for individual emoji depictions, many of them to Apple. I’ve been a little skeptical of Apple’s registration campaign, and I wonder if the Copyright Office would rethink some of those registrations in light of its determinations here.

[For more on the copyrightability of individual emoji depictions, see these posts:

- Depiction of Michigan as Hands Doesn’t Preclude Similar Depictions–High Five v. MFB

- Copyright Owner Claims Ownership Over Depicting Emoji Symbols in Multiple Colors–Cub Club v. Apple

- More Evidence That IP Law Protects Individual Emoji Depictions–Nirvana v. Marc Jacobs

- Copyright Office Won’t Register ‘Middle-Finger Pictogram’ As Literary Work–Ashton v. Copyright Office]

I’ve repeatedly raised concerns about the consequences of granting copyright protection for individual emoji depictions. First, it raises troubling weaponization/trolling possibilities. Second, it creates a rights thicket when referencing emojis that can be complicated and expensive to navigate. Third, it forces second comers to introduce their own detail variations to avoid identical depictions, which degrades the semiotic consistency of the emojis across different sets.

The board partially acknowledged these concerns by saying essentially that Apple would only have potential infringement claims over identical depictions. The board didn’t expressly reference fair use, but we have to assume that fair use would apply even when there is identical depictions of 100% of the work.

Still, even if the registration only protects identical depictions, it can still cause substantial trouble. The issued registration can act like a club to permit Apple to intimidate legitimate second comers and remixers who don’t want to spend the money to test the copyright’s boundaries or fair use limits. It leaves me wondering why Apple cares so much about these registrations, why it spent 6 years to get them, and under what circumstances it plans to assert the registrations.

For more on the wonderful world of emoji law and IP, see:

- Emojis and the Law, my flagship paper on the topic with a section on copyright protection for emojis

- Emojis and Intellectual Property, a brief and breezy survey of the topic.