Domain Name Lawsuits Are Stupid (and the Initial Interest Confusion Doctrine Is Too)–Wooster Floral v. Green Thumb

This case concerns the domain name WoosterFloral.com. It was initially owned by Wooster Floral, a florist in Wooster, Ohio. However, in 2014, the owner wound down the business and didn’t renew the domain name. The store manager then bought out the owner’s assets for $1, including the trade name, but not including the domain name (which had already lapsed). Meanwhile, a local competitor, Green Thumb, registered the domain name and auto-forwarded it to greenthumbfloralandgifts.com. The new Wooster Floral owner asked Green Thumb to transfer the domain name. Green Thumb’s owner declined, but she offered to sell the domain name for $2500. The court says the new Wooster Floral owner rejected the deal, “finding the price too steep.”

So, the Wooster Floral owner could have bought the domain name for $2,500, but instead chose litigation? Wut? $2,500 was too steep, but both parties instead spent tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars on litigating this case to the Ohio Supreme Court? And in an era when local businesses are struggling, can you imagine what each florist could have done with that money to build their businesses instead of forking it over to the lawyers? What an absolute waste. As I teach my students in Internet Law, money spent on trademark litigation could be invested in marketing instead, so make sure litigation has a better ROI than its alternative uses of cash. I cannot believe this litigation was the best investment for either party.

NOTE: $2,500 isn’t a particularly high price tag for domain names in the secondary market, but the seller apparently underestimated the prospective buyer’s willingness to make the economically irrational decision to litigate. This produces a domain name decision which we used to see 15+ years ago but rarely see nowadays. At least it makes me feel better that I still spend time covering domain names in my Internet Law course; and I feel slightly vindicated putting a domain name issue on my 2020 Internet Law exam.

For reasons not specified by the opinion, the plaintiff chose to sue in state court rather than the more typical federal court venue for domain name litigation. As a result, the case only deals with state law claims, not the Lanham Act or ACPA. The lower court ruled against the plaintiff on the trademark claim, and the plaintiff dropped it on appeal. That left only the state Deceptive Trade Practices Act claim. The Oho Supreme Court granted the petition on the following issue:

A competing business owner’s use of a competitor’s legally valid trade name in a domain name to divert consumers to the competing business’s website is a deceptive trade practice under R.C. 4165.02(A)(2) and is analyzed for likelihood of confusion at the time the trade name is used in the domain name, not by the content on the competing business’s website.

Although this is technically a false designation of origin case, both the majority and dissent analyze it essentially like a trademark case.

The majority says: “to run afoul of the statute, there must be a likelihood of confusion about the source of the goods and services not about where a particular domain name might lead….whether internet users are initially confused about the origin of a website does not matter” (Looks like there should have been a comma after “services”–I’ve sent the correction into the Reporter of Decisions). The court explains:

The redirected website, Green Thumb’s home page, clearly demonstrates Green Thumb’s name, logo, and address and makes no mention of the trade name “Wooster Floral” within the website. Any reasonable internet user looking at the website can tell that it is Green Thumb that is providing the goods and that there is no indication of sponsorship, approval, or certification of goods by another entity. And a consumer who doesn’t want to be there can quickly extricate himself by hitting ←

NOTE: The opinion actually displays the backarrow symbol, but I don’t consider it an emoji. I loved the line about the back button as a low switching cost, though this argument is 15+ years old.

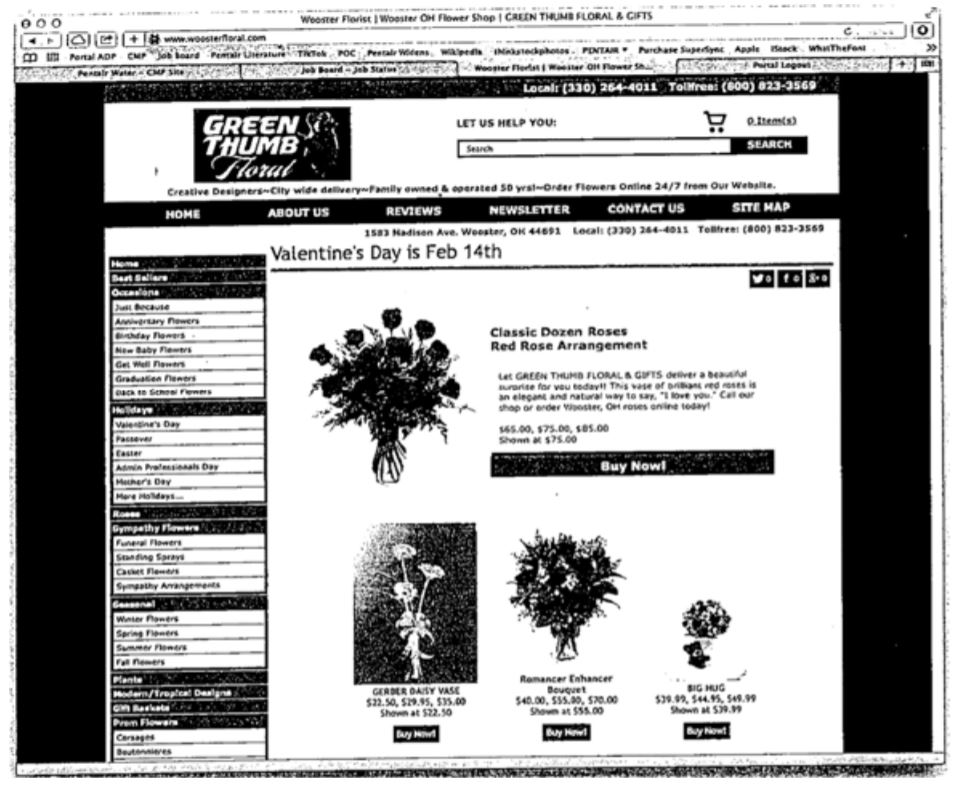

The majority included a screenshot showing the prominent Green Thumb branding when consumers visited woosterfloral.com:

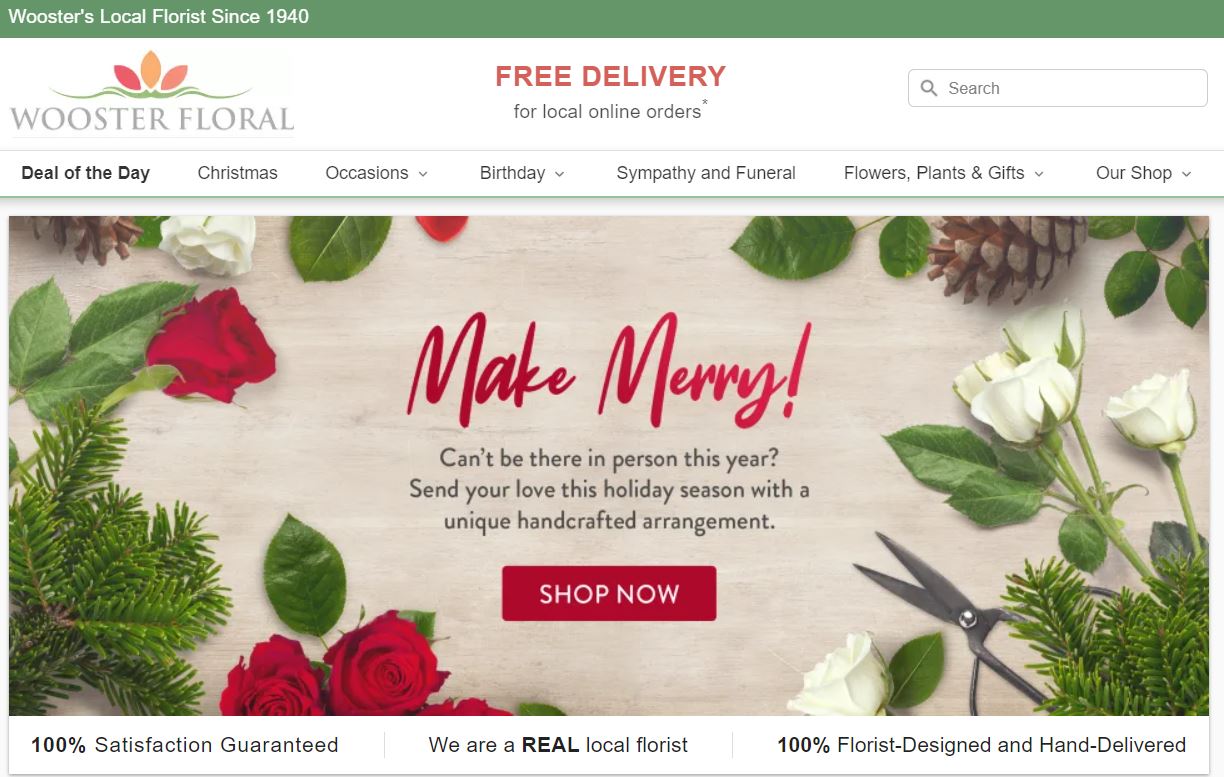

(Sorry for the crappy resolution of the opinion’s image; it may reflect that this case’s venerability). FWIW, the woosterfloral.com home page no longer prominently mentions Green Thumb as of December 20, 2020:

If Green Thumb is still operating the domain name, I wonder if the majority’s analysis would change if it saw this screenshot?

In further support of its ruling, the majority says the trade name “Wooster Floral” is weak. The trial court had ruled it was valid, a ruling not challenged on appeal, but I’d love to know more about this. Wooster Floral is a routine [geographic place] [generic noun for the items being sold] name that, under federal law, is descriptive and does not become protectable until it achieves secondary meaning. It’s possible “Wooster Floral” achieved secondary meaning, but even then, the Lanham Act’s descriptive fair use doctrine would permit competitors to use the terms “Wooster” and “floral” in their marketing. Certainly any competitor could truthfully say “We are a floral shop in Wooster, Ohio.” Would that extend to a competitor describing itself as Wooster Floral? Maybe.

The court continues:

It is plausible that a customer might type woosterfloral.com into a website because they are looking for Wooster Floral & Gifts’ website. But a consumer might also type the address simply because they are looking for a floral shop in Wooster. A reasonable internet user might assume that JohnDeere.com will likely lead to John Deere’s website, but that same user is much less likely to assume that woosterfloral.com will lead to a particular flower shop.

Hello, it’s 2020. No modern consumer, reasonable or not, will enter woosterfloral.com into a browser address bar hoping to find some rando local floral shop. Consumers gave up using domain name guessing as a search strategy 15 years ago because it yields consistently poor outcomes (typically popups and porn). As for johndeere.com, as I explained 15 years ago, there are multiple possible motivations for anyone using branded phrases as search keywords.

The majority opinion could have stopped here, but the plaintiff cited Lanham Act cases as precedent and the dissent discussed them too, so the majority engages with that literature. In particular, the majority discusses the initial interest confusion doctrine, and you can imagine how excited I am about that.

The court describes IIC: “customer confusion may be shown by the deceptive use of a trade name that sparks a consumer’s initial interest in a product, even if that confusion is dispelled before any sale occurs.” The majority says IIC is a “somewhat controversial theory,” but I think it’s more stupid than controversial. The dissent claimed IIC “is neither novel nor controversial,” to which the majority responds with a string cite of academic pieces trashing IIC, the latest of which was published in 2012.

The majority’s response to the dissent’s embrace of IIC is LOLNO: “the federal circuits largely have found the initial-interest-confusion theory inapplicable in situations like ours where any initial confusion is quickly dissipated once the consumer lands on the website.” Cites to Hasbro v. Clue (2000), Lamparello v. Falwell (2005), Passport Health v. Avance (2020), Toyota v. Tabari (2010). I still teach the Lamparello case in my Internet Law course for precisely this proposition. The majority also references some of the old 6th Circuit domain name jurisprudence, such as Taubman v. Webfeats (2003) and Interactive Products v. a2Z (2003).

The majority ends its opinion:

the question is whether a consumer landing on Green Thumb’s website is likely to be confused about the entity that will be fulfilling his order. The answer is clearly no. A consumer who buys flowers on Green Thumb’s website after initially typing in woosterfloral.com knows full well that his order is going to be fulfilled by Green Thumb.

Two judges dissent:

Federal courts have recognized initial-interest confusion, and we should recognize it too. Although I agree with the majority that federal courts have set a high bar for plaintiffs to prevail on a claim predicated on initial-interest confusion, I am unwilling to wholly reject the reality that a domain name itself provides source-identifying information or that consumers may be confused when a competitor uses another’s trademark or trade name in a domain name….I would recognize that a URL or domain name provides source-identifying information and that a defendant who uses a competitor’s trade name in its URL may cause initial-interest confusion about the source of the goods or services that the defendant is offering.

While the court reached the right outcome, this litigation might nevertheless make you think twice about transacting with either Wooster florist. When you are giving the gift of flowers to a loved one, you apparently are also giving the gift of litigation. No wonder flowers are so expensive.

Case citation: Wooster Floral & Gifts, L.L.C. v. Green Thumb Floral & Garden Ctr., Inc., No. 2020-Ohio-5614 (Ohio Sup. Ct. Dec. 15, 2020)

Pingback: News of the Week; December 23, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall()