Videogame Doesn’t Infringe Tattoo Copyright By Depicting Basketball Players–Solid Oak Sketches v. 2K Games

This case deals with a venerable and vexing copyright law problem: if a person doesn’t own the copyright to his/her tattoos, do other people infringe by accurately depicting the person? The answer surely has to be “no.” Otherwise, ordinary daily activities, such as photos and videos in public, become an unnavigable thicket of potential liability. Fortunately, this case decisively reaches the right result. However, it’s unclear how much it predicts future cases.

Background

This case involves the 2K14, 2K15, and 2K16 basketball videogames. The plaintiff claims the exclusive copyright license in five tattoos on three players depicted in the games: Eric Bledsoe, LeBron James, and Kenyon Martin. Apparently the plaintiff acquired exclusive copyright licenses from the various ink artists on a revenue share arrangement, thus weaponizing the tattoos.

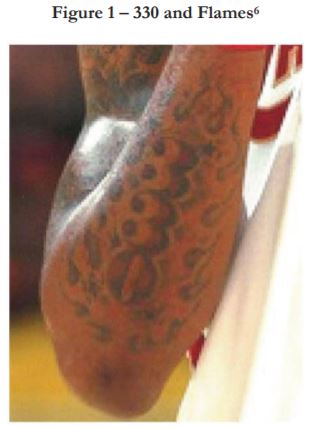

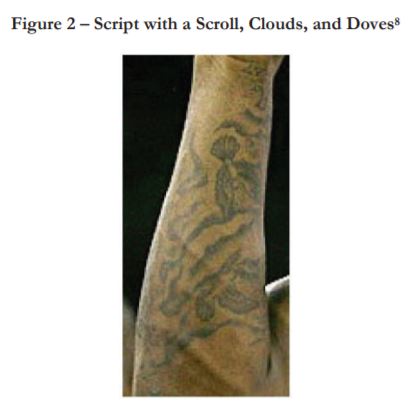

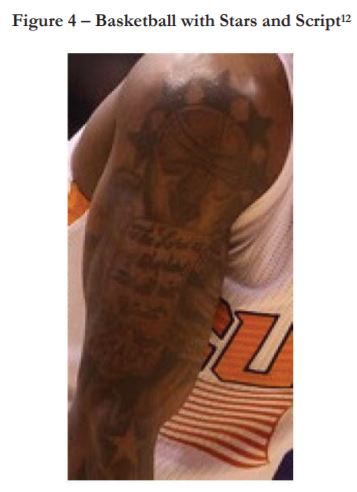

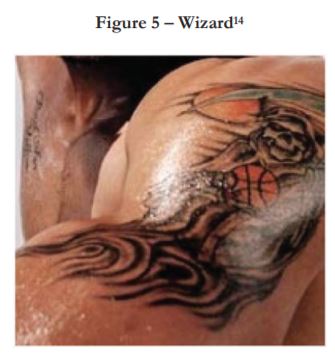

The court says the plaintiff never actually included depictions of the copyrighted works in its filings, which is an odd way to win a copyright case. I got these images from one of the defendants’ expert reports:

LeBron’s 330 and Flames Tattoo:

LeBron’s Script with a Scroll, Clouds and Doves tattoo:

LeBron’s Child Portrait tattoo:

Eric Blesdoe’s Basketball with Stars and Script tattoo (sorry if this is hard to see):

Kenyon Martin’s Wizard tattoo:

De Minimis

The court says the tattoo displays in the game qualify as de minimis use:

The Tattoos only appear on the players upon whom they are inked, which is just three out of over 400 available players. The undisputed factual record shows that average game play is unlikely to include the players with the Tattoos and that, even when such players are included, the display of the Tattoos is small and indistinct, appearing as rapidly moving visual features of rapidly moving figures in groups of player figures. Furthermore, the Tattoos are not featured on any of the game’s marketing materials.

When the Tattoos do appear during gameplay (because one of the Players has been selected), the Tattoos cannot be identified or observed. The Tattoos are significantly reduced in size: they are a mere 4.4% to 10.96% of the size that they appear in real life. The video clips proffered by Defendants show that the Tattoos “are not displayed [in NBA 2K] with sufficient detail for the average lay observer to identify even the subject matter of the [Tattoos], much less the style used in creating them.” The videos demonstrate that the Tattoos appear out of focus and are observable only as undefined dark shading on the Players’ arms. Further, the Players’ quick and erratic movements up and down the basketball court make it difficult to discern even the undefined dark shading.

We don’t see successful de minimis defenses very often, but this seemed like a logical application of the doctrine.

Implied License

The ink artists gave the players implied licenses to their tattoos because “(i) the Players each requested the creation of the Tattoos, (ii) the tattooists created the Tattoos and delivered them to the Players by inking the designs onto their skin, and (iii) the tattooists intended the Players to copy and distribute the Tattoos as elements of their likenesses, each knowing that the Players were likely to appear ‘in public, on television, in commercials, or in other forms of media.'”

That’s swell, but seriously, if you’re ever getting a tattoo, you should get an express license, right? Otherwise, your ink artists can sell out and try to weaponize your own tattoos against you.

Fair Use

- Nature of Use. “while NBA 2K features exact copies of the Tattoo designs, its purpose in displaying the Tattoos is entirely different from the purpose for which the Tattoos were originally created….the Tattoos were included in NBA 2K for a purpose—general recognizability of game figures as depictions of the Players—different than that for which they were originally created.” Replanting the tattoos into a videogame seems like a straightforward application of the transformative doctrine, even if the games were designed to be as realistic as possible. The court also credits the size reduction; limited observability of the tattoos; and the tattoos’ trivial percentage of game data (only 0.000286% to 0.000431% of the total game data). The games are commercial, but the tattoos are just an incidental part of the games.

- Nature of the Work. “the Tattoo designs are more factual than expressive because they are each based on another factual work or comprise representational renderings of common objects and motifs that are frequently found in tattoos.” LeBron’s child seems to fit the factual model; the flames apparently are a scenes-a-fair, but I’m not sure the court can fairly characterize the wizard as not expressive (even if wizards are a tattoo trope).

- Amount/Substantiality of Use. “it would have made little sense for Defendants to copy just half or some smaller portion of the Tattoos, as it would not have served to depict realistically the Players’ likenesses.”

- Market Effect. The transformative depictions means they aren’t substitutive. There were no realistic markets for the tattoos, either.

Implications

Overall, the court reaches the right result; and the fact that it relies on three independent copyright defenses bodes well for future tattoo copyright cases. Yet, the tattoos’ limited visibility in the game clearly worked in the defense’s favor, so future cases may be factually distinguishable. Unfortunately, this means we’re still likely to see vexing tattoo copyright cases in the future.

Case citation: Solid Oak Sketches LLC v. 2K Games, Inc., 1:16-cv-00724-LTS-SDA (S.D.N.Y. March 26, 2020). The complaint.

Prior Tattoo Copyright Blog Posts

Pingback: Videogame Can Replicate Musician's "Signature Move" (Unless It's a False Endorsement, Which It Isn't)-Pellegrino v. Epic Games - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()

Pingback: Humvee Can't Stop Depictions of Its Vehicles in the 'Call of Duty' Videogame-AM General v. Activision Blizzard - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()