Another TOS Formation Failure in the 9th Circuit–Godun v. JustAnswer

This case involves the JustAnswer service, which ensnares possibly unsuspecting consumers into an auto-renewal that consumers allegedly don’t want. JustAnswers’ TOS formation process was rejected in the California state courts. It fares no better in federal court.

Important nomenclature note: the panel repeatedly refers to the call-to-action as an “advisal.” The Berman opinion also used this term, but only once. The term “advisal” appears 29 times in this opinion, which confused me on two fronts. First, the term is not standard for this litigation genre. To be fair, neither is my preferred term, “call-to-action.” The absence of a standardized term is what leads the panel to embrace its own term. Second, the word “advisal” is not being used for its dictionary definition. The definition of “advisal” is giving advice, making it sound like a consumer disclosure than a legally operative call-to-action. I fear the “advisal” term will propagate due to this opinion, adding even more nomenclature confusion to a legal area already riddled with confusing and misunderstood jargon. Something to look forward to. 😵

* * *

Before getting into specifics, the panel “helpfully” summarizes the state of play:

we have not created a checklist for website designers. Nor have we generated per se design rules that must be followed for a contract to be formed between a website user and provider….a one-size-fits-all approach would undermine the fact-intensive, totality-of-the-circumstances nature of the analysis….’even minor differences’ in the design elements may make the difference in this fact-intensive analysis

In other words, everything is open to negotiation and debate. That seems likely to ensure a steady stream of appeals to the Ninth Circuit.

* * *

The court classifies all of the screens below as sign-in-wraps.

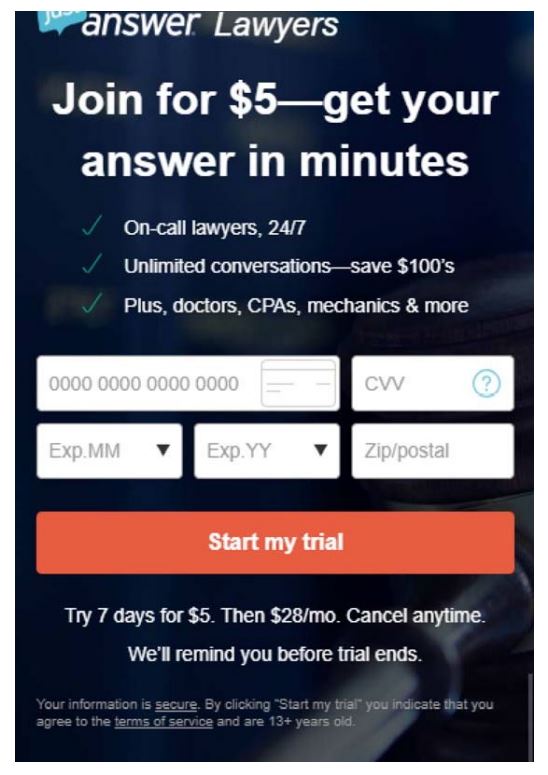

Davis’ screen:

The panel says:

The advisal text is printed in relatively small text and not located “directly above or below” the action (“Start my trial”) button. This creates the impression of being visually “buried.”

Additionally, the color of the advisal text blends into the background and is displayed in a lighter color than other text on the page. In fact, portions of the text are hard to read as they do not contrast with the lighter portions of the background image. This gray-on-gray presentation also suggests that the advisal is inconspicuous, and we would not expect a reasonable internet user’s attention to be drawn to it. While each of these factors may not be enough on their own to support Plaintiff Davis’s argument, under the totality of the circumstances, the advisal was not visually conspicuous.

Nelson’s page:

The panel says: “The advisal is not…located directly above or below the action button and is displayed in relatively small text.” Not good enough.

Godun/Faust/McDowell pages: Note: the panel indicates that the boxes were prechecked, and no one knows if consumers could uncheck the boxes.

and

The panel says: “The advisal lacked an explanatory phrase indicating that “By clicking connect now” or “By connecting,” or “By chatting,” etc., she agreed to the terms. Like the faulty advisals in Berman and Chabolla, it instead simply said “I agree” without explaining more….an advisal that simply states that “I understand and agree to the Terms and Conditions” but fails to “indicate to the user what action would constitute assent” is not enough to invite an unambiguous manifestation of assent.”

That’s some ticky-tack parsing of the call-to-action. Note that if the box had been unchecked and the consumer had to check it, the court would have deemed this a clickwrap and enforced it (it literally says so in FN 6). So the call-to-action wording isn’t the real problem; it’s the prechecked box that’s the problem. In other words, JustAnswers miraculously navigated to a legal deadzone by pre-checking the box AND not having a proper if/then call-to-action.

As a last-ditch argument, JustAnswers points out that Godun also navigated through this screen:

The panel doesn’t like this screen either:

the black background is outside the main frame of the screen. Placing the notice on the black border (coupled with an “x” button apparently permitting the user to close a dialogue box) creates the visual impression of being “tucked away” or not important to the transaction. While the page is generally uncluttered, the placement of the advisal on the black border creates an impression of visual discontinuity. This does not “capture the user’s attention” and direct her to the notice.

The distinction between the white field and the black border also seemed ticky-tack. The white call-to-action lettering is impossible to ignore if you see the “Start Chat” button, even if there is a visual separator.

* * *

Oof. Five different screens. All of them failed. An impressive display of futility. But also, I don’t have any sympathy for JustAnswers. They knew how to do it right. They just didn’t.

The takeaways from this ruling are obvious, and they aren’t new:

(1) Courts will pixel-police the formation screens in great detail.

(2) They will make all inferences regarding TOS formation against the drafter.

(3) If you want to avoid the first two points, use a two-click process (a “clickwrap”).

* * *

Judge Nelson, author of the panel opinion, wrote a concurrence to his own opinion. (This is not his first self-concurrence; and it feels to me like self-concurrences are becoming a status symbol among TAFS judges). It appears that his panel opinion went along with the other two judges as a matter of precedent, but he also objects to the precedent and registers his discontent in his self-concurrence.

First, he says that this call-to-action was reasonably conspicuous:

He explains: “if an internet user did not recognize that this underlined text is a hyperlink, she is not reasonably prudent.”

Second, he doesn’t like the ticky-tack demands for the if/then call-to-action requirement. He says:

we demand magic words—or, at least, we come very close…We got it wrong, the Second Circuit got it right [cite to the Klarna case], and we should pivot to follow its lead by revisiting Berman’s explicit advisement rule.

So in the snippet most immediately above, he would say that the “I agree” preface to the call-to-action would be sufficient.

Case Citation: Godun v. JustAnswer LLC, No. 24-2095 (9th Cir. April 15, 2025)