Web Page Framing Isn’t Trespass to Chattels–Best Carpet Values v. Google

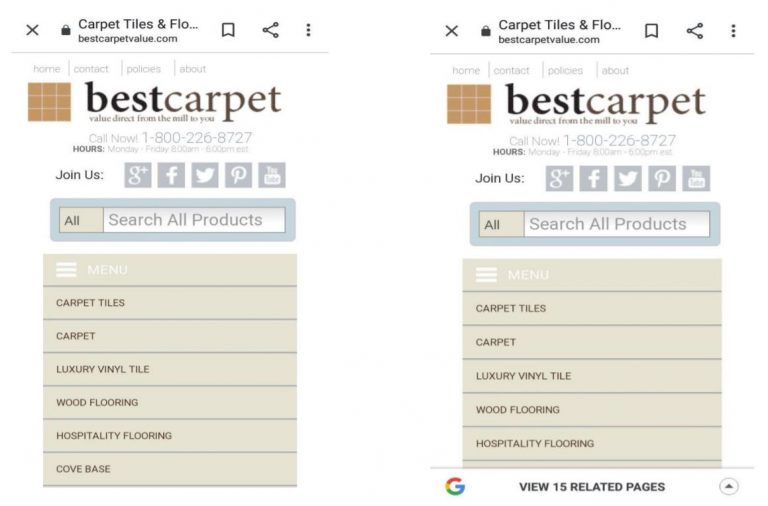

This case is an old-school turn-of-the-century throwback (and not the good kind). Google’s search app framed the web pages users visit, and the frame included ads. Some screenshots depicting the framing (the first image shows Google’s superimposed frame on the right; the second shows what happens if users click on the frame in the first image):

If this issue sounds familiar, it’s because framing generated huge discussion in Internet Law circles….20+ years ago. The plaintiffs lost all of the framing cases then, but here we are in 2024, still litigating framing cases. #YOLO.

Why are we revisiting this crusty old topic? The plaintiffs in this case apparently thought they were more clever than everyone else who looked at this issue over the past quarter-century. Instead of asserting copyright and trademark claims, they tried trespass to chattels. Voila! It was an audaciously mockable pivot…and yet, the district court judge shockingly bought the argument. My angst-filled blog post on that ruling.

Fortunately, the status quo has been restored. The Ninth Circuit concludes, as everyone knew, that framing isn’t trespass to chattels. Unfortunately, the court expresses this intuitively obvious result in a baroque, technical, and inaccessible opinion.

Trespass to Chattels

I teach my Internet Law students that the first step in the prima facie trespass to chattels analysis is to identify the chattel at issue. In a framing case, the plaintiffs’ web servers aren’t the affected chattel because the plaintiffs’ web servers delivered the web pages directly to users’ devices, after which the framer (Google) superimposed its frame on the web pages once the copies were in users’ RAM. Thus, the framer never interferes with the web servers.

The district court said the “website” was the chattel. This is the kind of ambiguous generalization I see on Internet Law final exams that get a C. By using an overly general descriptor, the analysis can sidestep key (and legally significant) technical distinctions. In this situation, the generic noun “website” collapses several different elements: the website hardware (the servers), the domain name, the web pages as electronic files, the web pages’ HTML code, the web pages’ substantive content, and more. In other words, the district court judge was imprecise about exactly what chattel was being trespassed.

The Ninth Circuit fixes that obvious error, saying the chattel in question “are the copies of Plaintiffs’ websites.” Even this correction is suboptimal. The “copies” in question are not copies in the abstract sense. They are the electronic copies of requested web pages that reside in the web user’s device RAM.

Once we qualify the copies as “electronic,” it becomes unmistakable that this case deals with intangible items, not traditional “chattel” that are, by definition, tangible items. For that reason, the Ninth Circuit could have easily said that electronic files categorically aren’t chattel and the trespass to chattels doctrine *never* applies to any manipulation of or interference with electronic files.

Instead of taking such a clean and intuitive approach, the court says that the plaintiffs don’t have any possessory interests in the electronic copies of their web pages once delivered to users’ devices:

Under Plaintiffs’ theory, they maintain a possessory interest in an intangible copy that (1) is created when a user visits a website via the Search App, (2) exists on the user’s device, and (3) is deleted by the user when they leave the page. Plaintiffs’ possessory interest is thus entirely dependent on actions taken by an individual user unassociated with Plaintiffs or their websites. A possessory interest does not lie under these circumstances.

I guess? This is a bass-ackward way of discussing the issue. We’re talking about electronic bits zinging around the network, and it’s mostly nonsensical to talk about who “possesses” those electronic bits. Worse, it’s not clear the users have a “possessory interest” in those bits due to the possibility that copyright and contract law that may limit what users can do with those bits. What if no one has a “possessory interest” in those bits? What are we even talking about?

The Ninth Circuit takes this baffling approach in part due to the 20-year-old Sex.com case (Kremen v. Cohen), which held that a domain name could be “converted.” Domain names are also intangible, as are the records documenting domain name ownership, yet the court held they were capable of being converted. Accordingly, the Kremen case has long vexed the trespass to chattels jurisprudence by collapsing the distinction between intangibles and tangibles for property law purposes. However, I think there are numerous ways a court could distinguish between an electronic record that determines purported ownership and the many other types of electronic files, ranging from Word documents on my hard drive to web pages floating around the Internet.

Instead, to honor precedent, the Ninth Circuit applies the ill-suited three-element Kremen test to decide when intangibles qualify as chattels:

1) “an interest capable of precise definition.” The court says “there is no single way to display a website copy.” That’s true. In my prior blog post, I said: “Underlying this litigation is an epistemological question: what does a “canonical” version of a web page look like? Every browser software makes its own choices about how to render a page; every browser software “frames” every web page with its software features; and every browser software lets users configure the display in ways that affect website owners’ expectations.” The Ninth Circuit explains:

This translation of website code into a visual appearance necessarily varies across browsers and devices. Plaintiffs respond that the lack of a fixed display does not defeat their property interest. Although in Kremen we held that updating records in a document did not defeat a finding of a property interest, Plaintiffs’ argument elides the core inquiry of the “capable of precise definition” part. California law requires that the property interest be “well-defined” and “like staking a claim to a plot of land at the title office.” A website copy possesses neither of these qualities

2) “it must be capable of exclusive possession or control.” The court says:

once the website copy is generated and sent to the user’s device, users have control over what to do with it—whether to click on a link on Plaintiffs’ sites, resize the page, navigate away from the page themselves, or click on one of the links provided in the results

This is true as a technical matter, but is it true as a legal matter? Copyright and contract law that may restrict legally what the user may do with the “copies” that are now resident in the device RAM.

3) “the putative owner must have established a legitimate claim to exclusivity.” The court says “Plaintiffs themselves recognize that they do not control how their websites are displayed on different devices or web browsers.”

The Kremen test is so obviously ill-fitting to this inquiry, but the court gets to the right place: “there is no cognizable property interest in website copies that may serve as the basis for a trespass to chattels claim under California law.”

Implied-in-Law Contract/Unjust Enrichment

The court says that these state law claims are preempted by copyright law. As I’ve already indicated, copyright law casts a huge shadow over any litigation about the disposition of web pages. To reinforce the point, the court says: “a commercial website, like computer software, may qualify for copyright protection.”

[Notice that, like the district court, the 9th Circuit misuses the generic descriptor “commercial website” in a way that collapses the many disparate component parts. I guarantee that copyright owners will quote this statement to improperly assert ownership over uncopyrightable components of their “commercial websites.” The 9th Circuit just chided the district court for sloppy nomenclature, then it makes the exact same error. Why is this so hard??? SIGH.]

As for the claims’ equivalency to copyright law:

We need not decide whether it is more appropriate to characterize Plaintiffs’ Complaint as implicating rights to (a) display or reproduce copies or (b) prepare derivative works because the Complaint invokes both rights and both rights are recognized under federal copyright law. Plaintiffs alleged that Search App “obtains a copy of the requested website page from the host web server and delivers the copy to the user by translating the website’s codes” and then “recreat[es] the website page on the user’s . . . mobile device screen.” Displaying and reproducing a copy of a copyrighted work (Plaintiffs’ website) falls squarely within the scope of 17 U.S.C. § 106. Plaintiffs further alleged that Search App “superimpose[ed] advertisements on their websites’ homepages and other landing pages” when displayed on screens. Google’s reproductions of Plaintiffs’ websites, which necessarily vary in appearance on users’ screens, can be recognized as an act of “prepar[ing]” “derivative works.” Either way, these allegations implicate the exclusive rights to copyright holders bestowed by federal statute.

The claims didn’t have the requisite “extra element” to overcome preemption because these claims were really just repackaged copyright claims.

Implications

Let’s start with the good news. The Ninth Circuit fixed the misguided district court ruling and reached the common-sense outcome that electronic files can’t be trespassed. This has the salutary effect of reinstating the status quo that web browser framing is legal.

Now, the less-good news.

First, this opinion requires mental gymnastics because sometimes intangible assets are legally treated as chattel (like domain name records). That outcome makes sense, but the collapse of the legal distinctions between intangibles and tangible assets ensures ongoing jurisprudential tensions.

Second, we desperately need more clarity on the Ninth Circuit’s positions regarding trespass to chattels in the wake of the hiQ v. LinkedIn chaos. I tried to teach the topic in my Fall Internet Law course and left the students with so many unanswered questions that they loudly complained that they didn’t understand the state of the law. (In fact, the students’ confusion was confirmation that they actually did understand the situation just fine, but it wasn’t satisfying to them). I’ve declared the trespass to chattels doctrine “unteachable” in its current status. Unfortunately, this opinion doesn’t do anything to clean up that doctrinal mess.

Third, the court’s decision also sidesteps the obvious issues with the jurisprudential line of web-browsing-as-copyright-infringement. If downloading the electronic copy implicates copyright law, could that copyright interest be weaponized to control the user’s use of framing or the framer’s activities? Under prevailing law, that question isn’t as ridiculous as it might sound.

Finally, I’ll note the parallels between this case and the Edible IP case in Georgia state court, where local lawyers claimed that Google’s keyword advertising program “converted” their intangible assets (their trademark/goodwill). That lawsuit also failed. To me, it’s a sign of desperation, not cleverness, when plaintiffs’ lawyers try to extrapolate offline physical-space doctrines to the intangible activities on the Internet.

Case Citation: Best Carpet Values, Inc. v. Google LLC, No. 22-15899 (9th Cir. Jan. 11, 2024)

Selected Related Blog Posts

* If “Trespass to Chattels” Isn’t Limited to “Chattels,” Anarchy Ensues–Best Carpet Values v. Google

* Georgia Supreme Court Blesses Google’s Keyword Ad Sales–Edible IP v. Google

* Creditors Can’t Seize Country Code Top Level Domains

* Ohio Appeals Court: GoDaddy can be Held Liable for Wrongly Transferring Control Over Domain Name and Email Accounts — Eysoldt v. ProScan

* Internet Rewards Program Class Action Survives Initial Motion to Dismiss — In re Easysaver Rewards

* Ninth Circuit Applies California law to Domain Name Ownership Dispute and Remands for Determination of Whether “Innocent Purchaser” Defense Applies — CRS Recovery, Inc. v. Laxton

* Ninth Circuit: Creditor Can Execute Against Domain Name Where Registry is Located — Office Depot v. Zuccarini

* Domain Names as Property Subject to Creditor Claims–Bosh v. Zavala

* Taking Intangible Electronic Files is Criminal Fraud–NM v. Kirby

* Sex.com — An Update