FitBit’s Contract Formation Upheld Despite Different Ways of Linking to the TOS—Houtchens v. Google (with Bonus Contracts Quick Links)

This is a consumer protection lawsuit against FitBit, now owned by Google. Google sought to send the case to arbitration based on the TOS provisions. The court sees this as a simple formation question because FitBit used a “clickwrap” (i.e., a checkbox confirming acceptance of the TOS in addition to the account creation button). Google represented, and the court accepted, that a consumer could not proceed with the account creation until the box was checked.

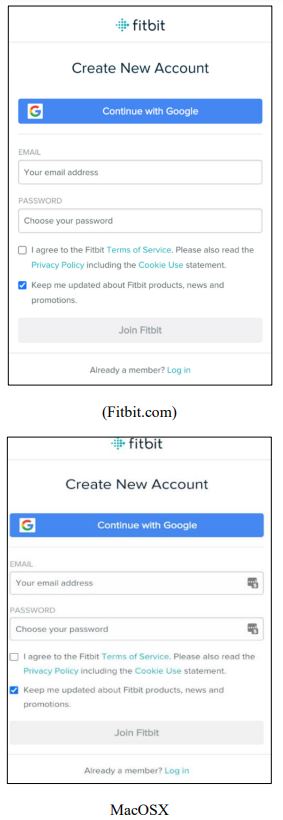

To get around the TOS’s arbitration clause, the plaintiffs argued that they didn’t realize the formation language linked to the TOS. Here are the screenshots at issue:

The court says:

In the first three screens, the hyperlinks to Fitbit’s Terms of Service are presented in blue text in a sentence that otherwise uses gray text; they are next to the box a user must select to accept the terms; and the screens on which they appear are uncluttered. Court’s [sic] have routinely found that such a presentation supplies reasonably conspicuous notice of hyperlinked terms….In the final screen, the hyperlinks are again presented next to the box that a user must select to accept the terms and the screen on which they appear is uncluttered; but instead of using blue font to distinguish the hyperlinks from the surrounding text, the page uses bold-underlined font. The Court finds that this page, too, provides reasonably conspicuous notice of the terms to which a consumer will be bound.

Although the court wasn’t explicit about it, notice what the court approved. In the first three screenshots, the TOS link is denoted solely by the offsetting blue-green color—no bold, no underline. In the final screenshot, the court says it’s OK that the TOS link is marked by the bold and underlined presentation, even though it’s in the same white-colored font. In other words, the coloring of TOS links shouldn’t affect TOS formation so long as consumers understand that it’s a link; and the courts are open to a range of different UIs indicating that something is a link. Still, you should never leave the court having to wonder what consumers thought.

The plaintiffs said they couldn’t remember seeing the TOS. The court says that’s irrelevant when “Google has offered evidence that Plaintiffs checked a box agreeing to Fitbit’s Terms of Service when they created their Fitbit accounts….Plaintiffs’ assertion that they may not have read the Terms of Service does not undermine their assent to the terms.” Two clicks FTW.

The plaintiffs argued that they were not warned of the additional service terms when they bought their devices. The court tersely dismisses this issue by focusing only on the service signup: “Plaintiffs were on inquiry notice of Fitbit’s Terms of Service due to the clickwrap agreement to which they assented when they created their Fitbit accounts. Fitbit’s alleged failure to include the Terms of Service or reference to the Terms of Service in the packaging of its devices does not negate this notice.” This outcome is consistent with other “Internet of Things” cases, such as the 23andMe litigation (and, in a sense, the ProCD v. Zeidenberg case from way back when). Still, it seems troublesome because it ignores that some contract was formed at point of purchase, and those terms should be relevant to governing the device and possibly whether or not the service TOS is an amendment, a conflicting contract, or something else. In particular, what recourse does the consumer have if they balk at the service TOS after buying their device? Can they return their device for a full refund? (That wasn’t possible with 23andMe, because the login to get the test results occurred after the test was consumed, yet the court shrugged off that concern). If the consumer balks at the service TOS and functionally bricks the device, there should be some meaningful recourse. The court sidestepped all of that.

Google overcame the unconscionability challenge because it gave consumers the ability to opt-out of arbitration. (Consumers could send an email within 30 days of purchase).

Case citation: Houtchens v. Google LLC, 2022 WL 17736778 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 16, 2022)

* * *

BONUS: Additional contracts links from the past six months

* Amadasun v. Google, Inc., 2022 WL 2829644 (N.D. Ga. July 19, 2022). Upholding the arbitration clause in Google Ads’ TOS.

* California Crane School, Inc. v. Google LLC, 2022 WL 3348425 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 12, 2022). Antitrust lawsuit over Google search engine ads gets sent to arbitration per Google’s TOS, but co-conspirator Apple doesn’t get the benefit of the Google TOS and thus no arbitration. SEPT. 2025 UPDATE: The Ninth Circuit upheld dismissal of the plaintiff’s case.

* Chien v. Bumble Inc., 2022 WL 17069842 (S.D. Cal. Nov. 17, 2022):

Rather than hiding the fact that users were agreeing to contract terms by proceeding through the App, Bumble presented an isolated page, akin to a pop-up, with the solitary purpose of alerting users to the updated arbitration agreement in the Terms and Conditions. In large bold font the notice alerted users that there were “[u]pdated terms and conditions of use.” There were no other buttons or information drawing the user’s eye away from the fact that Bumble was offering contractual terms to the user. Although users may have been inclined to click the bright yellow button so that they could continue swiping on the App, the fact that the yellow button said “I accept” would have further put the user on notice that they could be manifesting assent to an agreement. And though the hyperlink with the full extent of the Terms and Conditions stands out in terms of font only for being underscored, the Court finds that it was sufficiently apparent to a reasonably prudent user that the hyperlink existed because, unlike the links in Berman, the link here consisted of its own block of text and did not simply constitute part of the same sentence alerting the user to the terms and conditions. Furthermore, the other information within the blocker card puts a reasonably prudent person on notice that the Terms contained additional information not present on the screen: “The updated Terms contain an Arbitration Agreement that includes a class action waiver ….” and “Bumble users who signed up before January 18, 2021 will have the option to opt out ….”

* Rosskamm v. Amazon.com, Inc., 2022 WL 16534539 (N.D. Ohio. Oct. 28, 2022)

the text notifying the customer of the COUs when creating an account reads: “By creating an account, you agree to Amazon’s Conditions of Use and Privacy Notice.” That text referencing the COUs is linked in blue directly below the “Continue” button on the “Create account” page. The text referencing the COUs when a customer must “Sign-In” to their Amazon account reads: “By continuing, you agree to Amazon’s Condition of Use and Privacy Notice.” Again, this text is linked in blue immediately below the “Continue” button. Lastly, when placing an order, the text referencing the COUs reads: “By placing your order, you agree to Amazon’s privacy notice and conditions of use.” This text is also linked in blue and appears directly beneath the “Place your order” button. Because Defendant’s COUs are contained in language directly beneath the “Sign-in,” “Continue,” or “Place your order” buttons, in blue ink indicating a hyperlink, and not surrounded by other language or hidden in any way, the Court deems the COUs to be reasonably communicated to Plaintiffs, and thus enforceable.

* Johnson v. Meta Platforms, Inc., 2022 WL 4777586 (D. Md. Oct. 3, 2022). Upholding the venue selection clause in Instagram’s TOS.

* Chilutti v. Uber Techs, Inc., 2022 PA Super 172 (Pa. Superior Ct. Oct. 22, 2022). Uber’s TOS formation has had a checkered history in court, but this opinion really goes to an extreme. This passage gives some context for the judge’s normative objections:

a court should not enforce an arbitration provision in an Internet purchase agreement unless the court finds that the party agreeing to an arbitration provision was aware that he was waiving the right [to a jury trial]. It is reasonable to assume that if the arbitration provision is buried deep in webpages in tiny print, the person was not aware of the provision and it is unenforceable….With these Internet contracts, it is now easier than ever for corporations to bind inexperienced, unaware, and unsuspecting consumers to arbitration agreements with the simple click or swipe of their finger ─ all from the convenience of 3-inch by 6-inch smartphone screen.

Applying the Ninth Circuit’s Berman case, the court says Uber’s contract formation was a “browsewrap.” Hmm. The court explains:

Uber’s website and application did not provide reasonably conspicuous notice of the terms to which Appellants were bound. For example, in Shannon Chillutti’s case, the “terms and conditions” agreement was encapsulated in tiny, blue font at the very bottom of a cluttered webpage. The relevant text was not underlined or capitalized. With respect to Keith Chillutti, he was on the fifth screen of the registration process, after he had already provided substantive personal information, when the “Terms and Conditions” page could be reviewed in small font that, again, was not underlined or capitalized.

Because the court thinks that commercial arbitration clauses are analogous to criminal defendants making the informed decision to waive jury trials at potential peril of their liberty, the court demands a higher standard for TOS formation than other courts have required:

because the constitutional right to a jury trial should be afforded the greatest protection under the courts of this Commonwealth, we conclude that the Berman standard is insufficient under Pennsylvania law, and a stricter burden of proof is necessary to demonstrate a party’s unambiguous manifestation of assent to arbitration. This is accomplished by the following: (1) explicitly stating on the registration websites and application screens that a consumer is waiving a right to a jury trial when they agree to the company’s “terms and conditions,” and the registration process cannot be completed until the consumer is fully informed of that waiver; and (2) when the agreements are available for viewing after a user has clicked on the hyperlink, the waiver should not be hidden in the “terms and conditions” provision but should appear at the top of the first page in bold, capitalized text.

This is a classic layered notice problem. Sure, the waiver of a jury trial is significant, but there are dozens of other also-significant consequences of agreeing to TOSes, and they can’t all be simultaneously “highlighted” to consumers. So specially calling out the waiver of a jury trial for heightened consumer visibility is bizarre, especially because odds are that the jury trial waiver is further down on the consumers’ lists of things they want highlighted.

Having embraced this fiction, the court then starts to question everything about arbitration clauses in TOSes…

the definition of arbitration is not contained in the agreement and there is no link to the definition. Likewise, there is no explanation as to the difference between binding and non-binding arbitration in the agreement. Notably, if a party wants to review the AAA Rules that govern the process, they are required to click on a second hyperlink to access that document. Further, we believe that the term, “arbitration,” is ambiguous in that there is nothing to explain its meaning and any non-lawyer subscriber could easily believe that arbitration is simply another step in the litigation process that does not involve relinquishing the constitutional right to a jury trial in its entirety. As such, Appellants were not informed in an explicit and upfront manner that they were giving up a constitutional right to seek damages through a jury trial proceeding

I’m pretty sure Uber’s TOS is not the best place to do basic civics education LOL.