Plaintiffs’ Law Firm Can Reference Targeted Business’ Name In Ad Copy–McHugh Fuller v. Pruitt

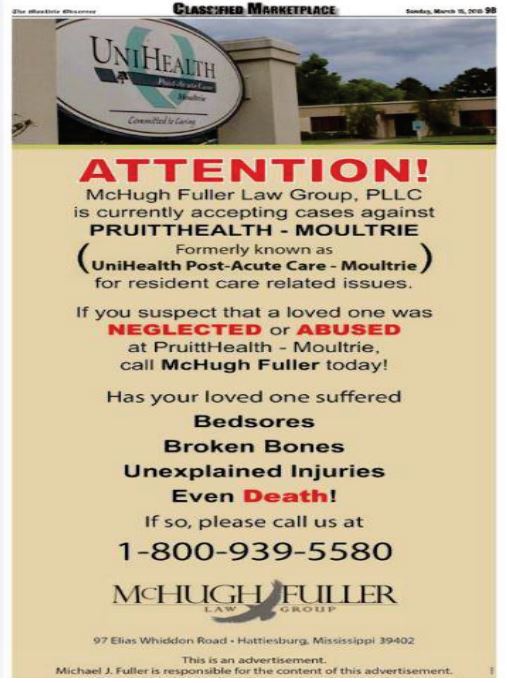

PruittHealth operates nursing homes in the Southeast. The McHugh Fuller law firm regularly sues nursing homes (their tagline: “Nursing Home Law…It’s What We Do”). To drum up business, in March 2015, it ran the following ad in the Moultrie, Georgia community as part of a larger Georgia-wide ad campaign targeting PruittHealth:

Apparently the advertisement successfully generated responses from potential clients: “since running ads targeting specific PruittHealth facilities in 2014, McHugh Fuller had received about 200 calls from potential clients, was engaged by roughly 50 clients, and filed about 11 negligence lawsuits against PruittHealth alleging that patients had suffered bedsores, broken bones, unexplained injuries, or death.”

Not surprisingly, Pruitt wasn’t too pleased with ads raising questions about the prevalence of neglect, abuse and death at its nursing homes. Citing tarnishment, Pruitt sued McHugh Fuller for trademark dilution under Georgia’s state trademark law. The trial court enjoined the ad. For reasons that are unclear to me, McHugh Fuller bypassed the intermediate appellate court and could appeal the injunction directly to the Georgia Supreme Court, which unanimously reversed the order and handed an unqualified win to McHugh Fuller.

Had this been a federal trademark dilution claim, it would have been an easy defense win. My understanding is that PruittHealth is a regional brand (I had never heard of it on the West Coast), so it may lack the required national fame. Furthermore, federal dilution law expressly excludes nominative uses, which is exactly what McHugh Fuller is making here. Unfortunately, state trademark dilution laws are a doctrinal backwater and often lack the features of a modern trademark dilution law like those in the Lanham Act. Thus, the Georgia Supreme Court’s opinion never once uses the phrase “nominative use” (indeed, the court expressly declines to interpolate into the state dilution claim a fair use defense analogous to the federal defense).

Nevertheless, the court finds its way to the same result. It says:

The ad used PruittHealth’s marks in a descriptive manner to identify the specific PruittHealth facility; indeed, McHugh Fuller was counting on the public to identify PruittHealth-Moultrie by the PruittHealth marks used in the ad. The ad did not attempt to link PruittHealth’s marks directly to McHugh Fuller’s own goods or services. McHugh Fuller was advertising what it sells – legal services, which are neither unwholesome nor degrading – under its own trade name, service mark, and logo, each of which appears in the challenged ad. No one reading the ad reproduced above would think that McHugh Fuller was doing anything other than identifying a health care facility that the law firm was willing to sue over its treatment of patients. In short, the ad very clearly was an ad for a law firm and nothing more.

All true, but notice how the court implicitly reintroduces the concept of consumer confusion into a tarnishment dilution claim. It’s also clumsy for the court to say that the law firm didn’t attempt to “directly link” the PruittHealth brand to its own. The law firm isn’t offering its services under the PruittHealth brand, but unquestionably the law firm sought to establish a cognitive link between the brands (i.e., “we’re the firm that sues PruittHealth!”). So avoiding the words “nominative use” leads to some unnecessarily convoluted explication.

The court goes on to suggest (without actually saying) that there may not have been any actual tarnishment. The court favorably cites an article by Prof. Sandy Rierson for the proposition that “cases where dilution by tarnishment has been found [all] involve the defendant’s association of a mark with sex or illegal drugs,” which isn’t the case here.

The court then summarizes:

trademark law does not impose a blanket prohibition on referencing a trademarked name in advertising…prohibit[ing] the use of PruittHealth’s marks to identify its facilities and services in any way, as the company urges, would raise profound First Amendment issues.

The trademark dilution doctrine remains controversial decades after Frank Schechter proposed it. We struggle to find empirical evidence showing that trademarks actually can be blurred or tarnished in consumers’ minds, and we continue to see brand owners wield the trademark dilution doctrine to advance anti-competitive and, as evidenced by this lawsuit, profoundly anti-consumer objectives. The 2006 amendments to the federal dilution law ameliorated some of federal dilution law’s worst attributes, and now we rarely see successful standalone dilution wins (i.e., that aren’t coupled with an infringement finding). This case reminds us that we still have cleanup work to do at the state level to fix antiquated dilution statutes; or better yet, rulings like this should prompt us to reconsider if and when we really need dilution laws at all.

Case citation: McHugh Fuller Law Group, PLLC v. PruittHealth, Inc., S16A0655 (Ga. Sup. Ct. Nov. 21, 2016)

Selected blog posts on trademark dilution:

* Brief Brand Reference in TV Ad Constitutes Trademark Dilution–Louis Vuitton v. Hyundai

* Puzzling 9th Circuit Dilution Opinion Over eVisa.com–Visa v. JSL

* Union Organizers’ Activist/Gripe Sites Don’t Support Trademark Claims–Cintas v. Unite Here

* Trademark Dilution Symposium Videos

* Griper Selling Anti-Walmart Items Through CafePress Doesn’t Infringe or Dilute–Smith v. Wal-Mart

* Lycos Not Liable for Objectionable Message Board Posting–Universal Communication Systems v. Lycos

* Competitive Keyword Purchase Doesn’t Contribute to Actual Dilution–Nautilus v. Icon

* Beebe on Trademark Dilution

* Trademark Dilution Revision Act of 2006