DMCA 512(c) Safe Harbor Applies to Embedding–Harrington v. Pinterest

This is a long-running class action copyright case (filed in 2020!) led by the photographer Blaine Harrington (now deceased). The plaintiffs complain about user-uploaded photos appearing in Pinterest’s off-website notifications to its users (e.g., email, in-app, and mobile push). This case was put on hold due to the Davis v. Pinterest case, but that case doesn’t preempt this one because Davis ultimately only addressed onsite displays, not off-site notifications. On summary judgment, the court says that Pinterest qualifies for 512(c) for in-line linking the UGC files into Pinterest’s notifications.

Service Provider. “Pinterest operates one of the largest social media platforms in the world, allowing users to upload content to servers operated by Pinterest.”

Repeat Infringer Policy. “Pinterest users earn a strike when they upload content that is the subject of a valid DMCA takedown notice, and accounts that accumulate too many strikes are terminated.”

Standard Technical Measures. The plaintiffs alleged the “International Press Telecommunications Council (ITPC) Metadata” was possible STM but didn’t adequately close the thought.

Stored at a User’s Direction

This factor vexes the court. The fact that Pinterest reformats the content doesn’t disqualify it from the safe harbor:

When a user uploads content to Pinterest, Pinterest automatically standardizes the file format and generates variants so it can algorithmically display Pins to other users in its signature grid formation. This is the same accessibility-enhancing format standardization and tag creation that was entitled to safe harbor in Ventura. This is also substantially similar to the video format standardization and “chunk” creation that automatically occurred in UMG when a user uploaded content. Pinterest does not modify user-uploaded content for use in e-commerce as the Atari defendant did. Nor does Pinterest significantly control what user-created Pins appear on its site as the defendant in Mavrix did. Although Pinterest’s machine learning algorithms do choose which Pins to display to which users, the Ninth Circuit specifically held that these algorithms exist for purposes of facilitating access

Still, what about the fact that the photos are displayed outside of Pinterest’s network? Given that those displays are in-line links, this case implicitly turns into an evaluation of the legitimacy/legality of embedding–though the court never uses that term… (In a footnote, the court acknowledges the server test and 512(d) but says it can ignore those).

The court says Pinterest’s embedding of UGC files in its offsite notifications still mean the files are being stored at the direction of users:

there appears to be little difference between an infringing display via web browser, which was entitled to safe harbor in Davis, and an infringing display via email. In both cases, Pinterest’s service merely provides the user’s software with a hyperlink. The software, be it a web browser or otherwise, then requests the image the hyperlink corresponds to from Pinterest’s server and displays it. Because both a hyperlink in an email and a hyperlink on a browser link back to images on Pinterest’s service, there is no clear reason why the first form of display would arise “by reason of the storage at the direction of a user” while the second would not.

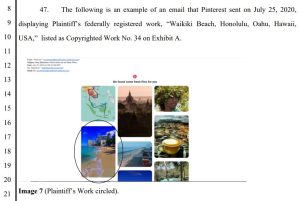

To be clear, the embedding caselaw doesn’t direct apply to Pinterest’s defense here. The embedding precedent generally addresses if embedding qualifies as direct infringement (as well as related isues like TOS consent), while this court was interpreting 512(c)’s statutory standard for storing files at a user’s direction. But I think the issues ultimately merge into one: if the incorporation test applied, the court could have said that the displayed image wasn’t displayed at the user’s direction because Pinterest incorporated into the email interface. (See the screenshot to the right, showing how the user-uploaded image looks integrated into the email).

To be clear, the embedding caselaw doesn’t direct apply to Pinterest’s defense here. The embedding precedent generally addresses if embedding qualifies as direct infringement (as well as related isues like TOS consent), while this court was interpreting 512(c)’s statutory standard for storing files at a user’s direction. But I think the issues ultimately merge into one: if the incorporation test applied, the court could have said that the displayed image wasn’t displayed at the user’s direction because Pinterest incorporated into the email interface. (See the screenshot to the right, showing how the user-uploaded image looks integrated into the email).

[Note: As a default setting, Gmail does not display in-line images in email. So if I received Pinterest’s notification emails, I would likely not have seen the image unless I took the extra step to show them. The court opinion doesn’t address this scenario.]

The plaintiffs tried a reductio ad absurdum argument that doesn’t persuade the court:

Harrington contends that extending Section 512(c) safe harbor protections to infringement outside of Pinterest’s platform would open the door for infringement on, for example, billboards in Time Square. But Section 512(c) is a fact-intensive inquiry. Though possible, like all things, Harrington’s hypothesis would require extreme facts outside the bounds of this case. The email notifications here merely provide a link to Pinterest users of material uploaded by other Pinterest users, and therefore narrowly facilitates access to users’ posts by sharing them with other users. By contrast, a billboard would presumably need to copy the image from the platform and display it to the general public—including those who are not Pinterest users—without providing a direct link to the user’s post. Such conduct would likely not be narrowly tailored at facilitating access to the user’s post.

To be fair, the plaintiffs have a point. If a Times Square billboard used in-line links to infringing user content to create the ad copy, this opinion would indicate that 512(c) still applied to the UGC. Rather than being ridiculous, this conclusion struck me as well within 512(c)’s sweet spot so long as the UGC remains hosted on Pinterest’s servers.

[Still, the plaintiffs’ hypothetical is ridiculous because (1) no one would rely on potentially breakable in-line linking for a high value venue like a Times Square billboard, and (2) ad copy goes through extra layers of legal review, so it would be weird for any ad to feature infringing content if the reviewers did their jobs].

Actual/Red Flag Knowledge. “Harrington never sent Pinterest a takedown notice or other prior communication identifying infringing material on the Pinterest service.”

Right and Ability to Control

Pinterest has presented evidence that the linked-to images in its notifications leads to user-uploaded images on Pinterest’s website, and Pinterest does not direct users to upload that content. The only facts potentially relevant to whether Pinterest has the “right and ability to control” the user-uploaded content is its algorithms and advertisements. On substantially similar facts, the court in Davis I found that Pinterest’s control over its algorithms and advertisements did not “constitute[ ] the kind of control that is necessary to lose safe harbor protection” under Section 512(c)….the connection between Pinterest’s algorithms and advertisements is insufficient to show Pinterest’s “right and ability to control” the allegedly infringing display

Direct Financial Benefit

a direct financial benefit requires facts showing revenue derived specifically from Pinterest’s display of Harrington’s copyrighted photo. Showing that advertisements generally appear in notifications is not enough

Implications

This opinion reaches a sensible “output agnosticism” about 512(c)’s applicability. So long as a UGC file remains hosted on the defendant’s servers, it doesn’t matter to 512(c) how many different ways the file may be accessed by others. This is consistent with the statutory text, which says that the defendant isn’t liable for “infringement of copyright by reason of the storage at the direction of a user of material that resides on a system or network controlled or operated by or for the service provider.” Because this statutory language doesn’t mention how the stored files are accessed, this court appropriately rejected the plaintiffs’ efforts to add doctrinal confusion where none existed.

This case is frustrating because the plaintiffs never sent 512(c)(3) takedown notices, and the case would not have existed if the plaintiffs had done so because Pinterest surely would have honored the takedown notices. In other words, this lawsuit was yet another attempt to overturn in the courts Congress’ 512’s notice-and-takedown statutory structure so that plaintiffs could win even if they never sent takedown notices. The judge rightly rebuffed that effort. Nevertheless, plaintiffs have made some progress undermining 512(c) in other cases, even cases that ultimately produced a defense win.

Case Citation: Harrington v. Pinterest, Inc., 2026 WL 25880 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 5, 2026)

Pingback: Copyright Takedown Notices Don't Require Services to Find and Remove Other Identical Copies-Athos v. YouTube - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()