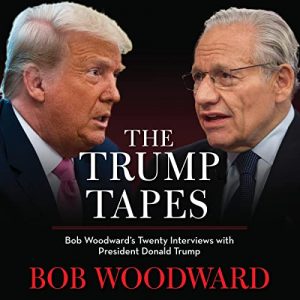

Trump Lost the Trump Tapes Ruling, But Could He Still Prevail? (Guest Blog Post)

by guest blogger Tim McFarlin

Is the Trump Tapes suit truly over? It’s been dismissed, but not without leave to move to amend for a third time. Would another amended complaint stand a chance? This question is why I’ve accepted Eric’s gracious invitation to chime in on a case that Tyler Ochoa has already expertly covered twice on this blog (here and here).

So as not to bury the lede, here’s how I think the case could perhaps be revived: by including a count specifically claiming state-law copyright infringement. I think the court opened the door to such a claim by deciding that Trump did not (and perhaps cannot) plausibly allege that his part in the interviews was “fixed” under federal copyright law.

The U.S. Copyright Act only applies to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” 17 U.S.C. § 102. Such fixation only can occur “by or under the authority of the author.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. For any work that is not so fixed, the Act specifies that “[n]othing in this title annuls or limits any rights or remedies under the common law or statutes of any State with respect to . . . subject matter that does not come within the subject matter of copyright as specified by sections 102 and 103, including works of authorship not fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” 17 U.S.C. § 301.

As it stands, in the court’s eyes Trump “played no role in ‘fixing’ either Woodward’s questions or his answers to Woodward’s questions,” and his consent to Woodward’s recording of the interviews did “not mean that fixation occurred” under Trump’s authority. I’m skeptical of the court’s reasoning here—that Trump’s disagreement with a later use of the recordings means that he did not authorize their initial creation—for reasons that Tyler explains well in his commentary. But taking it as the law of the case, as it is for now, I think it may bring everything outside the ambit of federal law.

In other words, given (a) that Trump is claiming he’s the author of his words (as a literary work) as well as of his vocalization of them (as a sound recording), and (b) that the court has apparently decided he cannot plausibly allege that either his words or vocalization was fixed under federal copyright law, I think the gravamen of the suit may shift to state-law copyright.

I’ve written fairly extensively about the possibility of state-law copyright in unfixed expression, e.g., this Journal of the Copyright Society piece, and I have a new article forthcoming in the Texas A&M Law Review on the potential for state-law copyright in AI-generated expression (draft soon to be posted on SSRN). The Copyright Society piece revolves around whether a formerly enslaved person named Mary Ann Cord had a New York copyright in an autobiographical story she told to Mark Twain, which he later wrote down and published, initially in the Atlantic, with credit and compensation to him alone.

My answer to that question was yes, Cord likely did have a copyright, particularly given Twain’s own recognition that her story “was a curiously strong piece of literary work,” so teeing up (as further detailed in this Wisconsin Law Review piece) a plausible claim for state-law copyright infringement against Twain, as well as against the Atlantic, which features the story on its website to this day.

Coincidentally, the court here has indicated that any state claim would, like Cord’s, be governed by New York law. So far, though, the court has held that Trump’s (non-copyright-based) state-law claims are preempted by the U.S. Copyright Act. But state-law copyright claims in unfixed works of authorship are, as noted above, expressly not preempted under that Act. 17 U.S.C. § 301.

The key going forward, then, is whether Trump can articulate how one or more of his answers, either in their substance or in his vocalization of them, constitute a work of authorship that the common law of New York should recognize and protect, at least in part, against the unauthorized (by Trump) publication of The Trump Tapes. (It would be under the common law because there is, to my knowledge, no New York statute on point. And the “at least in part” caveat is because any answers already included in Woodward’s book Rage were presumably published with Trump’s authorization, such that it’s likely only in Trump’s vocalization that a state-law copyright could still persist in them.)

I’ve not parsed all of Trump’s answers to form my own definitive view, though the court has already expressed its skepticism, at least as to their substance:

Indeed, if Plaintiff’s answers in The Trump Tapes are considered separate and apart from Woodward’s questions, the result is often unintelligible gibberish. To illustrate this point, the Court includes in the attached Appendix numerous examples of Plaintiffs’ responses, first separately and then together with Woodward’s questions. This exercise reveals that it is Woodward’s questions that make Plaintiff’s answers intelligible. Because an interviewer’s questions are of little to no value absent the interviewee’s answers, and because an interviewee’s answers are frequently unintelligible absent the interviewer’s questions, providing for the separate copyrightability of questions and answers in an interview setting is not rational, does not advance the purposes of copyright law, and ignores the reality that an interview must be considered as a unified whole.

But note the hedging: “often unintelligible gibberish” and “an interviewee’s answers are frequently unintelligible absent the interviewer’s questions.” I agree with “often” and “frequently,” though I think they make the conclusion at the end (“the separate copyrightability of questions and answers in an interview setting is not rational”) necessarily less than categorical.

Sometimes the substance of an answer, whether “in an interview setting” or otherwise, might separately constitute a “work of authorship.” Consider the question, “Tell me about that time in your life,” being answered with a long and vivid description, one which has all the hallmarks of autobiographical expression. And outside the realm of the hypothetical, consider how Cord told Twain her story of enslavement and emancipation in response to him simply asking her, “[H]ow is it that you’ve lived sixty years and never had any trouble?”

Beyond overbroad categorization, the problem with the court’s analysis of Trump’s answers is that it’s founded in “the animating principles of the Copyright Act.” But as explained above, if his answers were not fixed as defined in that Act, then it seems it’s the principles of New York common law that must be looked to in deciding if his answers are separately copyrightable.

Now, I’m not arguing that this situation is, on balance, desirable. Federal copyright is challenging enough to administer without bringing state law into the mix. But the dichotomy is how copyright seems to function in the United States, stemming from Congress’s apparent determination in 1976 that its power to “promote the progress of science . . . by securing for limited times to authors . . . the exclusive right to their . . . writings,” U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8, cl. 8 (emphasis added), is generally limited to works fixed by or under the authority of an author. My own hedging here (“seems to function,” “apparent determination”) is because claims in unfixed works have rarely been brought, much less decided. That such cases have been so rare is likely because it’s typically been presumed that “under the authority of the author” is synonymous with consenting to someone else pressing the “record” button.

My guess here is that if Trump were to include a state-law copyright claim in a third amended complaint, the court would reconsider its fixation analysis. That seems the easiest way to avoid the challenging additional issues that would come into the case, including the specter of the Dormant Commerce Clause, on top of the numerous issues already at play as detailed in Tyler’s posts. (Though a state-law copyright route would presumably avoid one of those issues—the prohibition on federal copyright in works prepared by officers of the U.S. government as part of their official duties, per 17 U.S.C. §§ 105 and 101—the policy implications of that avoidance are troubling.) So the court could plausibly revise its take on fixation, finding instead that Trump’s answers were all fixed under federal law because he permitted Woodward to press “record” and because, unlike in Garcia v. Google, there were no blatantly false pretenses involved in why Woodward was recording Trump. And even if, as Eric had suggested in Tyler’s first post, the “authority” to fix a work of authorship under the Copyright Act means something more than mere permission to fix (such as an intent at the time of fixation to claim federal copyright), the allegations seem to point to Trump having had that intent.

From there, for reasons well described in Tyler’s second post, the court’s decision that Trump’s answers are not separately copyrightable seems solid enough under federal law, particularly given the concern that journalism, and thus the “progress” purpose of federal copyright, would otherwise be hindered. But of course it’s not certain that this is how the court, or a court on appeal, would handle a state-law copyright claim.

In sum, then, I think there may be at least one way to revive the case—a claim of state-law copyright infringement—and it’ll be very interesting (at least to me) to see what happens if it’s included in a proposed third amended complaint.

Pingback: Trump’s Lawsuit Over The Trump Tapes is Dismissed (Trump v. Simon & Schuster) — Guest Blog Post - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()