Trump’s Lawsuit Over The Trump Tapes is Dismissed (Trump v. Simon & Schuster) — Guest Blog Post

By Guest Blogger Tyler Ochoa

[UPDATE: for bonus coverage, see Prof. McFarlin’s supplement to this post.]

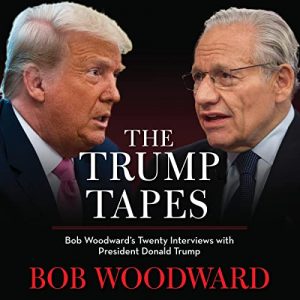

Last week, a federal judge in New York dismissed a lawsuit filed two-and-a-half years ago by then-former President Donald Trump against journalist Bob Woodward and his publisher, Simon & Schuster, over publication of The Trump Tapes: Bob Woodward’s Twenty Interviews with President Donald Trump. Trump v. Simon & Schuster, Inc., Case No. 1:23-cv-06883, 2025 WL 2017888 (S.D.N.Y. July 18, 2025).

Last week, a federal judge in New York dismissed a lawsuit filed two-and-a-half years ago by then-former President Donald Trump against journalist Bob Woodward and his publisher, Simon & Schuster, over publication of The Trump Tapes: Bob Woodward’s Twenty Interviews with President Donald Trump. Trump v. Simon & Schuster, Inc., Case No. 1:23-cv-06883, 2025 WL 2017888 (S.D.N.Y. July 18, 2025).

The lawsuit involves sound recordings of 19 interviews that President Trump voluntarily gave to Woodward between December 2019 and August 2020, plus one interview from 2016 (when Trump was still a candidate). More than eight hours of excerpts from those recorded interviews were published by Simon & Schuster in October 2022 as an audiobook, and transcripts were published in paperback and ebook formats. The Second Amended Complaint sought a declaratory judgment that Trump was a joint author and copyright owner of the recordings, or in the alternative, that he was the sole author and copyright owner in his interview responses; plus compensatory and punitive damages and disgorgement of profits, which the lawsuit (absurdly) valued at almost $50 million. It also pleaded state-law claims for an accounting of profits, unjust enrichment, and breach of contract.

I previously blogged my “preliminary analysis” of the case when the original complaint was first filed. On revisiting that blog post more than two years later, I am pleased how much of my original analysis still holds up, despite some substantive disagreements with the ruling. I will recap some relevant portions of that blog post as needed; but for a full analysis of all of the issues, please see the original post.

How We Got Here

The lawsuit was first filed in the Southern District of Florida on January 30, 2023. The original motion to dismiss was rendered moot by the First Amended Complaint, filed on April 24, 2023. On May 18, 2023, discovery was stayed pending the outcome of the second motion to dismiss, which was filed the next day. On August 4, 2023, the court granted the defendants’ motion to transfer venue to the Southern District of New York. Trump v. Simon & Schuster, 2023 WL 5000572 (N.D. Fla. Aug. 4, 2023). The Second Amended Complaint was filed on November 13, 2023; and the parties refiled their papers, including the motion to dismiss, opposition, and reply, in the first week of December 2023. (The briefs are available here.)

And then, the parties waited. And waited. On December 17, 2024, over one year later, Trump’s attorney sent a letter to the court, asking it to expedite the case. The court denied the motion the same day, saying “The Court is at work on the outstanding motion,” and refusing to lift the stay of discovery. Four months later, on April 25, 2025, Trump’s counsel sent another letter, requesting a decision within 30 days. The court did not respond. Two months later, on June 26, 2025, Trump’s counsel sent yet another letter, complaining “we remain in limbo, unable to proceed with discovery or obtain a resolution on the merits,” and implicitly threatening to file a petition for a writ of mandamus in the Second Circuit. Finally, the court issued its ruling on July 18, 2025, two-and-a-half years after the case was filed, and more than 19 months after the motion to dismiss was fully briefed.

The Issues

In my previous blog post, on February 13, 2023, I identified “six major issues raised by the case” that Trump would have to overcome:

First, were the recorded interviews a copyright-eligible “work of authorship”? Second, if so, who is the initial owner of the copyright(s)? Third, is Trump’s claim of ownership barred by 17 U.S.C. §105, as a “work of the United States Government”? Fourth, if not, can Trump circumvent the registration requirement by seeking a declaratory judgment, or will he have to comply with the registration requirement? Fifth, assuming Trump owns a valid copyright, did he grant an implied license to Woodward to publish transcripts of the interviews and/or the recordings themselves? Sixth, assuming Woodward published copyrighted material without Trump’s authorization, was he permitted to do so, either as a fair use, or by the First Amendment?

Two weeks later, on February 28, 2023, Trump’s counsel filed an application to register a copyright in the The Trump Tapes (as published) as a work of sole authorship, with himself as the author. (I have no idea whether my blog post informed Trump’s counsel of the registration requirement.) The Copyright Office issued the registration (Registration #SR0000975712) on October 13, 2023, but as work of joint authorship. Under 17 U.S.C. § 410(d), “[t]he effective date of a registration is the day on which an application, deposit, and fee, which are later determined … to be acceptable for registration, have all been received in the Copyright Office,” so the effective date was backdated to February 28, 2023. By filing a Second Amended Complaint that included the registration, Trump’s counsel took the fourth issue that I identified off the table.

The court’s decision involved only the first two issues outlined above. Because it found the case barred by the second issue, the court did not address the remaining issues.

The Merits: Joint Authorship

On the first issue, as I wrote in my initial blog post:

“Original, as the term is used in copyright, means only that the work was independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works), and that it possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity.” [Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340, 345 (1991)] The words spoken, and the manner in which they were spoken, were original to Woodward and Trump, and there is no doubt that they are minimally creative. The inescapable conclusion is that the recorded interviews are copyrightable works of authorship, both as sound recordings and as literary works.

Although it did not expressly say so, the court implicitly accepted the premise that The Trump Tapes was an original work of authorship. “Although the Copyright Act does not explicitly address interviews, courts have afforded them protection as “literary works,” “sound recordings,” or “compilation[s].” [Slip op. at 16.] Instead, the court focused on the second issue: who is the legal author of The Trump Tapes?

As I wrote in my original blog post:

A “joint work” is defined as “a work prepared by two or more authors with the intention that their contributions be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole.” [§101] … Questions and answers are normally interdependent; often the answers only make sense in the context of the questions. If the parties wanted to claim authorship of an interviews as a joint work, they may do so.

Case law, however, has imposed two additional requirements. [See Childress v. Taylor, 945 F.2d 500 (2d Cir. 1991) …] First, each author’s contribution must be independently copyrightable; that is, it must consist of original expression (as opposed to ideas or research). [945 F.2d at 507-09 … ] … Second, the parties must have intended to be joint authors. [945 F.2d at 506-07 … ] Here, it seems quite clear that neither Woodward nor Trump intended to be joint authors with each other….

Thus, under existing case law, the answer is quite clear: the interviews are not joint works.

The district court agreed. It quoted Childress and two other Second Circuit cases on the elements of joint authorship [Slip op. at 17-19]; and it marshalled all of the allegations in the Second Amendment Complaint indicating that neither party intended to be joint authors [Slip op. at 19-20]. The court also relied on the fact that both the initial Complaint and the First Amended Complaint sought sole authorship and alleged that “President Trump never sought to make a work of joint authorship.” [Slip op. at 20 n.10] “Litigation is not a game, and where — as here — a complaint’s allegations directly contradict allegations made in earlier pleadings, courts may disregard the contradictory allegations in resolving a motion to dismss.” [Id.]

The court also pointed to “objective factual indicia” indicating a lack of intention to be co-authors: the interview tapes were compiled, edited, and published by Woodward and Simon & Schuster, without Trump’s involvement [Slip op. at 21-22]; and although Trump is credited as a joint reader on the audiobook (“Read by Donald J. Trump and Bob Woodward”), all published versions credit Bob Woodward as the sole author (“By Bob Woodward”). [Slip op. at 22-23] (The court dismissed an online Barnes & Noble advertisement that credited both as authors, on the ground that the views of third parties were legally irrelevant; only the intentions of the purported joint authors were material. [Slip op. at 23 n.11])

Trump argued that his certificate of registration created a rebuttable presumption of joint authorship that was sufficient to defeat a motion to dismiss. [17 U.S.C. § 410(c)] The court rejected this argument. “The presumption of ownership accompanying a copyright registration may be rebutted by … evidence that the registrant is not an author of the work.” [Slip op. at 25] “Moreover, … where parties submit conflicting adverse copyright registration applications, the Copyright Office does not sit as a tribunal resolving those competing claims…. When conflicting claims are received, the Office may put both claims on the record if each is acceptable on its own merits.” [Slip op. at 26] (Note that although we speak of registering a copyright, the statute consistently says that what is registered is a copyright “claim.” [17 U.S.C. § 408(a); 17 U.S.C. § 410(a); 17 U.S.C. § 411(a)]) “Where … a court is faced with conflicting or adverse registrations, it must make an independent determination as to ownership, and [it] may concluded that no competing registration has prima facie validity.” [Slip op. at 26] Because there were conflicting registrations, and Trump’s registration was contradicted by his allegations, the court concluded that the Second Amended Complaint “does not plausibly allege joint authorship.” [Slip op. at 28]

Commentary: This portion of the judge’s decision is quite correct under current case law. As I wrote in my previous blog post:

Second Circuit case law is clear: there cannot be inadvertent joint authorship. In 16 Casa Duse, LLC v. Merkin, 791 F.3d 247 (2d Cir. 2015), … both parties sued, each claiming exclusive ownership of the movie footage. The court held that because each of them was seeking a declaration of sole ownership, the parties could not be joint authors. Because their contributions were inseparable, the court therefore had to determine which one of them was the “dominant” author …

I also wrote that “[i]n my opinion, this decision was incorrect; there should be limited situations where the parties have created a joint work through collaboration in fact, even if they subjectively did not intend for the work to be a joint work.” I adhere to that opinion. The Second Circuit’s position makes sense in the context of relatively unequal contributions, where there is a “dominant” author and someone else makes helpful suggestions which the dominant author is free to accept or reject. It does not make sense where the contributions of the parties are relatively equal. The Second Circuit’s holding in 16 Casa Duse gave the producer the equivalent of work-made-for-hire ownership without satisfying the statutory requirements of that doctrine.

Nonetheless, I cannot fault the district judge for following binding Second Circuit precedent. And the Second Circuit is notorious for almost never taking cases en banc, so it is almost certain that if there is an appeal, this part of the ruling will be affirmed. Since there is no circuit split (the Ninth Circuit and the Seventh Circuit agree with the Second Circuit on this issue), it is also highly unlikely that the U.S. Supreme Court would agree to take the case.

The Merits: Divided Authorship

So if The Trump Tapes are not a work of joint authorship, who owns the copyright? As I wrote in the earlier blog post, the practice of the Copyright Office is clear:

“The U.S. Copyright Office will assume that the interviewer and the interviewee own the copyright in their respective questions and responses unless (i) the work is claimed as a joint work, (ii) the applicant provides a transfer statement indicating that the interviewer or the interviewee transferred his or her rights to the copyright claimant, or (iii) the applicant indicates that the interview was created or commissioned as a work made for hire.” [Compendium of Copyright Office Practices (3d ed. 2021) (Compendium III), §719]

The interviews cannot meet the statutory definition of a work made for hire: Trump was not an employee of either Woodward or Simon & Schuster, and a “specially ordered or commissioned” work cannot be a work made for hire unless it falls within one of nine specified categories … and there is a signed written agreement specifying that the work is made for hire. [17 U.S.C. §101] A transfer of copyright ownership also requires a signed writing. [17 U.S.C. §204(a)] Thus, in the absence of a signed writing, [under the Compendium] Woodward and Simon & Schuster cannot claim a copyright in Trump’s responses to the interviews [or vice versa] unless the work was a “joint work.”

(This explains why the Copyright Office issued the registration to Trump as a “joint work” rather than as a work of sole authorship)

The district court, however, rejected the Copyright Office’s position. The Compendium was not the product of notice-and-comment rulemaking, so it would not have been entitled to Chevron deference even before Chevron was overturned by Loper Bright. Instead, “the Compendium is a non-binding administrative manual that at most merits deference under Skidmore…. That means we must follow it only to the extent it has the ‘power to persuade.’” [Slip op. at 44, quoting Georgia v. Public.Resource.org, Inc., 590 U.S. 255, 271, 140 S.Ct. 1498, 1510 (2020), quoting Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944)] For that reason, the Compendium states that “[t]he policies and practices set forth in the Compendium do not in themselves have the force of law and are not binding …” [Compendium III, at 2] The district court cited six cases in which courts had rejected a position of the Copyright Office as set forth in the Compendium. [Slip op. at 45-46]

Instead, the court held that question-and-answer interviews are a single unitary work for purposes of copyright law, for several reasons. First, “Plaintiff’s responses and Woodward’s questions have ‘little or no independent meaning standing alone,’ and thus the interviews reflecting their exchanges must be treated as what they are: a unified, integrated work.” [Slip op. at 43] The court illustrated this point with a 22-page Appendix of excerpts comparing the question-and-answer transcripts with Trump’s responses alone; without the questions, “the result is often unintelligible gibberish.” [Slip op. at 43 n.16] Second, case law almost uniformly rejects the idea that an interviewee has a copyright interest in the interview. Two courts rejected such an argument on the theory that the interview responses are “ideas” rather than “expression,” but the court was not persuaded by that rationale, saying one court improperly made a “value judgment” and the other improperly required “careful thought and preparation” to claim a copyright. [Slip op. at 31 n.12 and 32 n.13] The court was more persuaded by the rationale that “an interviewee is not an “author” who “fixe[s]” a work “in a tangible medium of expression.” [Slip op. at 29] “As a general rule, the author is the party who actually creates the work, that is, the person who translates an idea into a fixed, tangible expression entitled to copyright protection.” Community v. Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730, 737 (1990). [Slip op. at 29, 30, 33] “Here, Woodward recorded the interviews at issue, … and thereby fixed the interviews in a ‘tangible medium of expression.’” [Slip op. at 33]

“Fixation can, of course, occur ‘under the authority of the author,’ 17 U.S.C. § 101, even where the author does not personally perform the act of fixation.” [Slip op. at 35, collecting cases] “Here, the SAC pleads that Plaintiff consented to Woodward’s recording of the interviews, whereby the interviews were ‘fixed in a tangible medium of expression” for purposes of the Copyright Act.” [Slip op. at 36] “Such consent does not mean that fixation occurred ‘under the authority of [Plaintiff],’ however.” [Id.] The court cited Garcia v. Google, 786 F.3d 733, 744 (9th Cir. 2015) (en banc) for the proposition that “where the fixation of a work is ‘in derogation of [a party’s] permission,’ the fixation is not done ‘under the authority’ of that party.” Here, although the fixation was not in derogation of Trump’s permission (he gave his consent to be interviewed and for Woodward to record the interviews), the subsequent use of the recordings allegedly was in derogation of Trump’s permission.

The court also cited Del Rio v. Virgin America, Inc., 2018 WL 5099720 (C.D. Cal. June 28, 2018), in which a voice-over actress went to a studio and was asked to record the FAA regulations for airline safety. As she was doing so, “[s]omeone in the room pitched the idea for a rap sung by a young child,” and she spent the next three hours improvising a sound recording of the flight-safety regulations as a rap song performed in a child-like voice. The recording subsequently “went viral” and was used in Virgin Airlines’ on-board air-safety video. Plaintiff alleged she had never signed a contract or release with Defendants or any other party. The defendants made the same argument as in this case: she was not an “author” of the recording because she was not the one who had fixed it in a tangible medium of expression. The court acknowledged Garcia v. Google as precedent, but it actually held to the contrary:

Taking the allegations in the light most favorable to Plaintiff, the Complaint sufficiently alleges that Plaintiff fixed her performance by or under her authority. Though discovery might reveal facts counter to the allegations in the Complaint, Plaintiff alleges that she “alone created the voice, melody, and rhythm for the rap heard in the Virgin Safety Video.” … Though Defendants might have had a role in creating the rap that could bear on the question of joint authorship, … [t]his situation is not sufficiently similar to Garcia, where “[h]owever one might characterize Garcia’s performance, she played no role in the fixation.”

2018 WL 5099720, at *6.

More persuasive to me was the court’s public policy reason for not granting an interviewee a separate copyright in his or her interview responses:

By splitting the copyright interest in an interview into two parts, neither of which alone is commercially valuable as a stand-alone work, the interviewer’s work is essentially stripped of value, forcing potentially costly negotiations with the interviewee in order for the journalist to utilize the interview, which cuts against the central goal of copyright law.

Slip op. at 40, quoting Mary Catherine Amerine, Wrestling Over Republication Rights: Who Owns the Copyright of Interviews?, 21 Marquette Intell. Prop. L. Rev. 159, 173 (2017).

Ultimately, the court concluded that “the work resulting from an interview is an inseparable unitary whole,” and that Trump “does not have a copyright interest in his stand-alone interview responses.” [Slip op. at 46]

Because Trump lacked a copyright interest, the court did not address the remaining issues: whether Trump’s claim was barred by 17 U.S.C. §105, because his interview responses were a “work of the United States Government”; and whether the use was a fair use. The court did note, however, that both of those were “fact-intensive” defenses that generally are not amenable to resolution on a motion to dismiss. [Slip op. at 47 n.17]

Commentary

Having decided that each interview was a unitary work, the court was faced with competing copyright registrations, one from Simon & Schuster and one from Trump, and it ruled out both of Trump’s legal theories: that The Trump Tapes were a work of joint authorship, or that they were a work of divided authorship. Although the court did not directly answer the question of who owns the copyright in The Trump Tapes, the implications of its decision are clear: the sound recordings were authored by Woodward, the interviewer who “recorded the interviews at issue, … and thereby fixed the interviews in a ‘tangible medium of expression,’” [Slip op. at 33] and the copyright(s) in those sound recordings was (were) assigned to Simon & Schuster. (Thus, somewhat more precisely, each interview was a unitary work, and The Trump Tapes is a compilation or collective work comprising twenty such unitary works.)

As a purely statutory matter, I am not entirely persuaded by the court’s conclusion that Trump cannot be one of the authors of those interviews, just because he was not the one who “fixed” the interviews by pressing the record button. As the Copyright Office pointed out, the only choices are sole authorship, joint authorship, or work-for-hire status (unless one of those default choices is altered by a signed, written agreement). Because the Second Circuit’s case law ruled out joint authorship status, and the work clearly was not a work-made-for-hire, the only choice left to the court was sole authorship. But the cases that persuaded the court all involved audiovisual works, which can be distinguished on the ground that the camera work contributes at least as much copyrightable expression as the interview itself. Moreover, both Garcia v. Google and 16 Casa Duse v. Merkin involved scripted audiovisual works where the actors spoke lines authored by others, using sets, costumes, lighting, and camera work created by others. Audiovisual works present a much stronger case for not disaggregating the work and therefore for finding one party to be the “dominant” author (and copyright owner) and other party to be subsidiary. But unlike an audiovisual work, or even a studio recording with sound engineers, in my opinion there is no “authorship” involved in just pushing a “record” button. The only authorship in formal interviews are the questions and the answers, which are a collaborative enterprise in which copyrightable expression is produced by two authors, not just one.

Thus, in my opinion, it is inconsistent to conclude that Trump contributed approximately half of the original expression to a copyrightable work, but to also conclude that Trump cannot be an author because he himself did not “fix” the copyrighted work. In my previous blog post, Eric and I disagreed on this point. I expressed the opinion that Trump was an “author” and that his consent to be recorded was sufficient for the work (or his portion of the work) to be “fixed … by or under the authority of the author.” Eric expressed the opinion that Trump could not be an author, because for Eric, “the statutory requirement of ‘authority’ connotes something more than mere ‘consent to record.’” The district court came down squarely on Eric’s side of the debate. To me, that is too similar to the outdated “instance and expense” test for work-made-for-hire under the 1909 Copyright Act: because the interviews were initiated and recorded by Woodward, they were made at his “instance and expense,” so (the work is a work made for hire and) Woodward is the sole owner of the copyright. The court’s decision gives Woodward the same outcome as a work made for hire without having to satisfy the more demanding statutory requirements of the 1976 Act’s work-for-hire definition.

At the same time, I am also persuaded by the judge’s holding that an interview is a single unitary work; and his demonstration of that (comparing the responses alone to the full question-and-answer transcript) is quite persuasive. It makes sense not to “make Swiss cheese of copyrights” by dissecting them into their component parts (which was Eric’s primary objection in our fixation debate). To the extent my earlier blog post relied on the Copyright Office’s opinion that interview questions and answers should be disaggregated, I have changed my mind on reconsideration. But that brings me back to a point on which I have not changed my mind: in my opinion, both parties were “authors” of original expression, so the work should be considered a work of joint authorship, notwithstanding their subjective intention not to be joint authors. That is especially true of the sound recordings, in which Trump’s “performance” is at least as important an expressive contribution as his actual answers.

The result of joint authorship would be that Woodward and Simon & Schuster can each publish The Trump Tapes without further permission, but they would have to share the profits from that publication with the other joint author, unless the action was barred by one of the other defenses (“work of the U.S. government,” implied license, fair use, or the First Amendment). I think that is the correct result under the statute, purely as a doctrinal matter; and in many contexts (such as a celebrity profile), I would be fine with that result. But where the interview subjects are public officials and political candidates, I admit that I find the result to be distasteful, especially where (as here) there is clearly an adversarial relationship between the subject and the journalist, notwithstanding Trump’s consent to be interviewed.

Furthermore, I am also persuaded by the public policy reasons identified in Amerine’s article. Journalists have an ethical obligation to obtain consent for an interview to be “on the record,” but they should not have to negotiate further to be able to publish such an interview without compensating the subject. “Checkbook journalism” is also an ethical violation in the journalism profession. For reasons of public policy, it makes a lot of sense to conclude that the copyright in an interview lies solely with the journalist as a default matter; and that the interview subject should have to negotiate a written agreement if they want to share the profits. Narrowly construing the requirement that a work be fixed “by or under the authority of the author” serves as a convenient doctrinal hook for reaching that result. It also avoids the need to resort to the First Amendment as a Constitutional check on the Copyright Act (which so far the Supreme Court has been unwilling to do). And it was the only way for the court to decide the case on a motion to dismiss, as the other defenses depended on factual issues that would have had to wait for a motion for summary judgment.

Bottom line: While as a doctrinal matter I would have preferred that the court decide the case on one of the other grounds outlined in my blog post, as a matter of public policy the court reached the correct result. I can live with a little doctrinal discomfort when the result protects both journalists and the public interest in holding public officials and public figures to account.

Preemption

Trump also brought state-law claims for an accounting of profits, unjust enrichment, and breach of contract. (He abandoned his claim for breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. [Slip op. at 48 n.20]) The court dismissed all of the claims on the ground they were preempted by Section 301 of the Copyright Act.

Section 301 preempts state-law causes of action if two conditions are met: first, the plaintiff must be claiming rights “in works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible medium of expression and come within the subject matter of copyright.” Second, the state-law right must be “equivalent to any of the exclusive rights within the general scope of copyright.” [17 U.S.C. § 301(a)] Importantly, “[t]he scope of copyright for preemption purposes … extends beyond the scope of available copyright protection.” [Slip op. at 48-49 n.21, quoting Forest Park Pictures v. Universal TV Network, Inc., 683 F.3d 424, 429-30 (2d Cir. 2012)] Thus, “Plaintiff’s state-law claims may be preempted even where he does not possess a valid copyright interest.” [Slip op. at 49 n.21]

On the first prong, “[t]here is no dispute here that The Trump Tapes come within the subject matter of copyright.” [Slip op. at 51 (cleaned up)] “The paperback and audiobook versions of The Trump Tapes … are, respectively, a ‘literary work’ and a ‘sound recording’ …” [Id.]

Under the second prong, state-law rights are “equivalent” when they “may be abridged by an act which, in and of itself, would infringe one of the exclusive rights.” [In re Jackson, 972 F.3d 25, 43 (2d Cir. 2020)] The unjust enrichment claim simply pleads that defendant was enriched at plaintiff’s expense and that equity requires restitution. Citing Second Circuit precedent, the court ruled (without further explanation) that “Plaintiff’s unjust enrichment claims are not qualitatively different from a copyright infringement claim.” [Slip op. at 53, citing Briarpatch Ltd. v. Phoenix Pictures, Inc., 373 F.3d 296, 306 (2d Cir. 2004)] This makes sense, because any enrichment could not be at Trump’s expense if he did not have a property interest in the copied material.

Breach of contract claims usually are not preempted, because the existence of a contract (offer, acceptance, mutual consideration) usually is an “extra element” that goes beyond the exclusive rights protected by copyright law. But this is not categorical: where the contractual promise sought to be enforced is simply to refrain from exercising one of the exclusive rights, the claim is preempted. Here, “[t]he gravamen of the [breach of contract] claim is that Woodward ‘distributed’ the alleged protected work (Trump’s responses to Woodward’s interview questions) in violation of their [alleged] agreement.” [Slip op. at 55] The court cited Second Circuit precedent “reject[ing] the argument that exceeding the scope of a license entails an ‘extra element’ that saves a breach of contract claim from preemption.” [Slip op. at 55, citing Universal Instruments Corp. v. Micro Sys. Eng’g, Inc., 924 F.3d 32, 49 (2d Cir. 2019)] Otherwise, any use exceeding the scope of a license agreement could be pleaded both as a copyright claim and as a breach of contract.

Finally, “claims for [an] accounting based on the defendant’s alleged misappropriation and exploitation of a copyright work are preempted by the Copyright Act.” [Slip op. at 57]

Political Implications

Trump is well-known for filing meritless lawsuits against journalists and others, in an attempt to silence and/or deter criticism of him and his policies. This lawsuit fits that pattern, although there are two reasons why it might be a little different. First, as I opined in my initial blog post, although “Trump will almost certainly lose the lawsuit as it is currently framed,” nonetheless, I thought it was “not completely crazy,” and I opined that “an amended complaint … stands a significant chance of surviving a motion to dismiss.” (For now, at least, I was wrong about that.) Second, Trump did not ask for an injunction, only damages and an accounting of profits. On the other hand, that may have been strategic, as a request for an injunction would likely have put the judge into full “the First Amendment does not allow government censorship” mode. And any claim seeking $50 million in damages is likely to have a deterrent effect, whether meritless or not.

An interesting twist is that there has always been a third defendant in the case: Paramount Global, the parent company of Simon & Schuster as well as other media properties, such as CBS and Viacom. In July 2024, Paramount Global announced a planned merger with Skydance Media. That merger must still be approved by the Department of Justice; and it is widely believed that Paramount agreed to pay $16 million to settle a meritless lawsuit against CBS and 60 Minutes in order to smooth the way for the merger (which will net Paramount Chair Shari Redstone $2.5 billion). Three days after criticizing the settlement as a “big fat bribe,” late-night host Stephen Colbert announced that CBS was canceling his show, Late Night with Stephen Colbert, at the end of the season. Although the Trump v. Simon & Schuster lawsuit was filed well before the merger was planned, Trump will likely appeal the dismissal; and it is possible that he may demand a settlement in this case before the merger is approved.

Conclusion

The federal district court decided that 1) the twenty interviews in The Trump Tapes were not works of joint authorship, because neither party intended to be a joint author; 2) each interview is a unitary work, so that the questions and answers cannot be disaggregated and ownership cannot be divided between Woodward and Trump; 3) Trump does not have a copyright interest in the interviews, because Woodward was the person who “fixed” them “in a tangible medium of expression”; and 4) even though the interviews were fixed with Trump’s consent, they were not fixed “by or under [his] authority,” so he could not claim to be an author. It also held that his state-law claims were preempted by the Copyright Act.

While the court doubted that Trump could plead a claim sufficient to overcome a motion to dismiss, it gave Trump one more opportunity to move to amend, on the condition that the proposed Third Amended Complaint be attached, and that the motion explain how the defects identified in the ruling have been addressed. [Slip op. at 58]

If Trump chooses to stand pat and appeal the ruling, the court’s holdings are likely to be upheld on appeal; and even if Trump succeeds in defeating the motion to dismiss, he still has numerous obstacles to overcome on a motion for summary judgment (as explained in my prior blog post). Trump would be better advised to cut his losses and to abandon the case; but that is not in his nature. Instead, I expect him to appeal, and to use the planned merger with Skydance as leverage to try to extract a settlement from Paramount Global.

Pingback: Links for Week of July 25, 2025 – Cyberlaw Central()