Quantifying the Media’s Section 230 Misreporting in 2020

2020 was filled with terrible memories, including the COVID pandemic/shutdown and Trump’s coup attempt, so it’s easy to forget how close we came to losing Section 230. In May 2020, Trump issued his performative executive order purporting to repeal Section 230, which was followed by the NDAA fiasco in December where Trump vetoed raises for our military servicemembers because Congress didn’t simultaneously repeal Section 230. The NDAA nonsense put numerous Congressmembers on record as anti-Section 230, and Sen. McConnell introduced a performative Section 230 repeal bill.

2020 was filled with terrible memories, including the COVID pandemic/shutdown and Trump’s coup attempt, so it’s easy to forget how close we came to losing Section 230. In May 2020, Trump issued his performative executive order purporting to repeal Section 230, which was followed by the NDAA fiasco in December where Trump vetoed raises for our military servicemembers because Congress didn’t simultaneously repeal Section 230. The NDAA nonsense put numerous Congressmembers on record as anti-Section 230, and Sen. McConnell introduced a performative Section 230 repeal bill.

Trump’s repeated attacks on Section 230 acted like a school exam for the mainstream media. Would they call out Trump’s brazen censorship and ignorance? Would they stenographically repeat his (and his acolytes’) many lies and misstatements about Section 230? Or would they engage in journalists’ typical anodyne bothsiderism, treating the keep-230 and repeal-230 camps as equally legitimate?

Kathryn Alexandria Johnson, a master’s student at the University of North Carolina Hussman School of Journalism and Media, wrote a thesis called “Characterizations and Misrepresentations of Section 230—A Content Analysis.” The thesis does a media studies analysis of the Section 230 coverage by the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. As you would expect from a media studies scholar, the thesis is fairly anodyne itself. Nevertheless, it’s impossible not to be horrified by the mainstream media’s failures in covering Section 230 when it mattered the most.

[Note: I thought the thesis’ focus only on the NYT and WSJ was fine. If you think that’s too limited, you are welcome to extend her study and methodology to other outlets.]

I’m going to highlight three findings from the thesis.

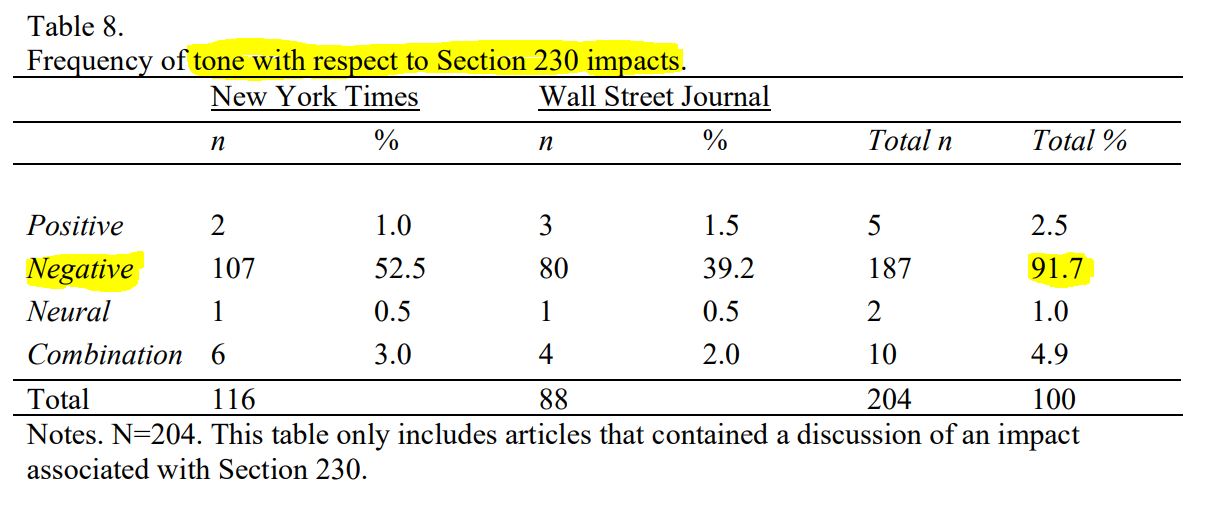

1) Reporters shat on Section 230 in 2020. The thesis doesn’t isolate whether the coverage’s anti-230 skew came from reporters repeating the invective coming from the Trump/#MAGA camps or the reporters’ own biases (such as their own personal concerns about “Big Tech”). Nevertheless, the consequences are overwhelming: 92% of the NYT/WSJ stories had a negative framing of Section 230.

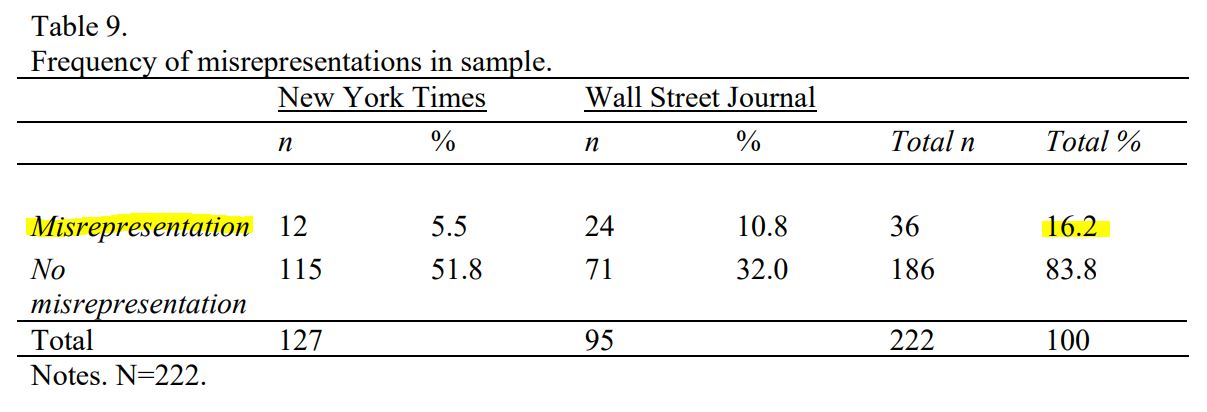

2) About 1 in 6 Stories Made an Error About Section 230. Getting 84% right is B-level work in school, but we expect better from two of the country’s flagship newspapers.

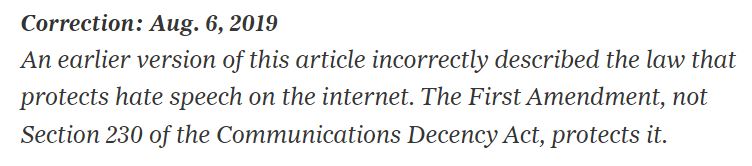

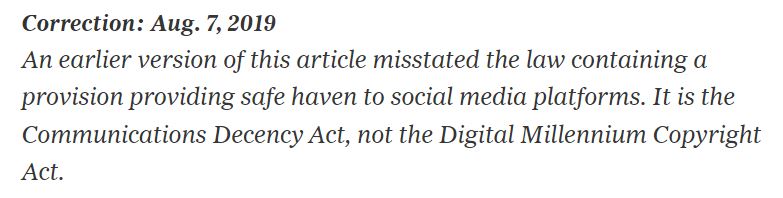

Honestly, the media’s error rate about Section 230 felt far higher than 1-in-6. Remember these terrible and repetitive NYT corrections?

August 6, 2019:

August 7, 2019:

October 4, 2019:

July 10, 2021:

(There may be others–this was a quick-and-dirty assemblage). For more on the topic of newspapers correcting their Section 230 coverage, see this post.

(There may be others–this was a quick-and-dirty assemblage). For more on the topic of newspapers correcting their Section 230 coverage, see this post.

3) Reporters Made Unforced Errors About Section 230. While the media’s propensity for bothsiderism ensures the verbatim replication of false claims about Section 230 from ignorant or bad-faith sources, the Section 230 errors flagged in the thesis came from the reporters themselves (or their editors, who don’t get a separate callout):

The thesis offers some suggestions for journalists covering Section 230, including:

- “journalists should strive to accurately and concisely describe what Section 230 is and what it does….journalists should rely more on verified sources of authority such as the statute itself, case law that illustrates the proper application of the law, or experts in this subject area when preparing articles for publication.”

- “journalists should make clear that they convey that Section 230 is not what allows platforms to engage in content moderation….journalists should avoid using the term “safe harbor” to describe Section 230. Doing so will help further distinguish Section 230 from the DMCA”

Conclusion

In addition to those sensible recommendations, I have some to add:

Reporters Need to Recognize Their Self-Bias Against Section 230. The media loves the “anti-Big Tech” narrative because it comports with their intuition (big = bad), allows for journalists’ standard framing pitting two sides against each other, and supports doomsayer narratives that drive reader engagement. Knowing this propensity, reporters owe it to their readers to recognize and overcome their own biases.

Politicians Are a Prime Source of Misinformation About Section 230. Very few politicians publicly characterize Section 230 correctly. Reporters are used to repeating government sources verbatim and then contextualizing those statements with other sources, but using that approach for their Section 230 coverage ensures the spread of politicians’ misinformation. This issue will heat up again if/when the Republicans take control over one or both chambers of Congress in 2023, because Section 230 will be one of their top targets and most of their public statements about Section 230 will be demonstrably false. Will reporters continue their anodyne approach in those conditions?

If Reporters Don’t Acknowledge Section 230’s Benefits, They Are Doing Their Bothsiderism Wrong. We saw how bothsiderism amplified not-credible statements during the Trump era, so sometimes reporters need to call BS on the lies their sources are giving them. However, if reporters are going to keep doing their standard bothsiderism, it requires them to present Section 230’s benefits alongside the negatives. This is not about noting how Google or Facebook derive huge profits due to 230, but actually noting the many ways that we as individual Internet users benefit from Section 230 on an hourly basis. The media’s overwhelming emphasis on the negatives of Section 230, without equal coverage of the counterbalancing benefits, contributes to a widespread perception that Section 230 only has problems and has no merit at all, which fosters a toxic regulatory environment because regulators and their constituents get the misperception that changing Section 230 couldn’t make things worse.

Reporters Need to Screen Section 230 Sources Carefully. As Section 230 became a mainstream topic and a partisan talking point for both parties, there was a flood of newcomers to the Section 230 field. Some of them have valuable perspectives, but far too many are not credible at all–they don’t understand what Section 230 actually says, don’t track the caselaw to understand how courts are actually applying it, don’t understand that all media policies involve tradeoffs, haven’t thought through the likely countermoves from Internet services in response to any policy changes, or are just cranks or trolls who will advance their pet theory or bash Big Tech regardless of the policy merits. Further, some reporters are pretty good about highlighting possible source conflicts based on financial ties to the major Internet services, but they can ignore conflicts from other sources, such as the dark money coming from other tech companies who hate 230 or Google.

Public Surveys About Section 230 Need to Acknowledge the Unrelenting Negative Coverage of Section 230. I don’t trust surveys that ask citizens if they like or dislike Section 230. Those surveys are going to mirror the pervasive negative comments from politicians and the mainstream media. I think it’s far more insightful to ask citizens if they like the policy principles underlying Section 230. They do: 1, 2.

Finally, the thesis empirically demonstrates how Section 230 was a brutal year for pro-Section 230 sources who regularly interviewed with reporters. It felt like we were on a never-ending treadmill to combat the misinformation and unjustified antipathy towards Section 230. It was truly exhausting. Odds are high that we’ll get to do it all over again starting in 2023.