Messaging Apps Raise Tricky E-Discovery Issues (Guest Blog Post)

by guest blogger Philip Favro

Several recent court cases spotlight the challenges that messaging apps present in litigation. In particular, these cases show that messaging apps—whose features may cause message content to either be kept or deleted—have an outsized impact on litigation results. Those features—which vary from one app to the next—include the ability to:

- “Unsend” messages (Facebook Messenger),

- Share emotions using a “tapback” function (iMessage),

- Automate the deletion of messages on a user’s app (iMessage), and

- Automate the deletion of messages on both the sender’s and the recipient’s apps (Signal and Telegram).

Facebook Messenger’s “Unsend” Feature – Fast v. GoDaddy.com LLC, 340 F.R.D. 326 (D. Ariz. 2022).

Fast v. GoDaddy is exemplary of the problems that Facebook Messenger’s “unsend” feature can present in litigation. This feature allows a user to “unsend” a message, i.e., disable a recipient’s access to messages the user previously sent. In Fast, plaintiff used the “unsend” feature to prevent a former colleague (“Mudro”) from disclosing 109 relevant Facebook Messenger messages. Plaintiff’s action effectively prevented Mudro—who was helping plaintiff marshal evidence to support her discrimination claims—from producing the original, unaltered messages in response to a GoDaddy subpoena. Nevertheless, Mudro produced timestamps indicating the dates when she received the 109 “unsent” messages from plaintiff, the contents of which were replaced by the wording “this message has been unsent.” After GoDaddy filed its motion for sanctions against plaintiff, plaintiff finally produced 108 of the 109 “unsent” messages in their original, complete form just days before Mudro’s scheduled deposition, with one notable exception: Plaintiff permanently deleted a message memorializing an analysis she conducted with Mudro evaluating the strength of the evidence supporting her claims. The court concluded that the circumstances surrounding plaintiff’s elimination of this key message—the use of the “unsend” feature to prevent Mudro from disclosing the message’s contents and then plaintiff’s subsequent deletion of that message—warranted the issuance of an adverse inference instruction at trial (the court imposed additional sanctions to address plaintiff’s spoliation of other evidence including Telegram messages – see section four below). Shortly afterwards, plaintiff voluntarily dismissed her discrimination claims with prejudice, but not before paying $10,000 to GoDaddy in monetary sanctions. According to the court, the $10,000 sanctions award was the price of dismissal given plaintiff’s widespread and brazen spoliation of Facebook Messenger messages and other relevant data. See Fast v. GoDaddy.com LLC, No. CV-20-01448-PHX-DGC, 2022 WL 901380 (D. Ariz. Mar. 28, 2022).

iMessage’s “Tapback” Feature – Mod. Remodeling, Inc. v. Tripod Holdings, LLC, No. CV CCB-19-1397, 2021 WL 3852323 (D. Md. Aug. 27, 2021).

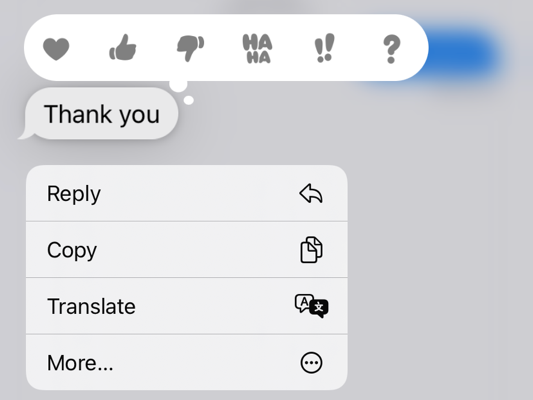

Many iPhone users find the iMessage “tapback” feature to be an indispensable form of communication; a quick way to acknowledge receipt of a message from their discussion partner by assigning an “expression” and without having to type out or dictate a responsive note. Displayed below, this feature is activated after the user touches the message at issue on an iPhone (or iPad) screen:

But if a message participant is using an Android phone or sending an SMS message rather than an iMessage, the “tapback” feature generates a replica of the original message, a sometimes annoying phenomenon, cluttering up messaging conversations with the likes of “Bob Emphasized Your Message” or “Alice Loved Your Message,” with the original message repeated afterwards. If a user deletes the original message but not the “tapback,” it can signal the existence of a deleted message, leaving adversaries and courts with a roadmap that can establish the user’s attempt to eliminate message content.

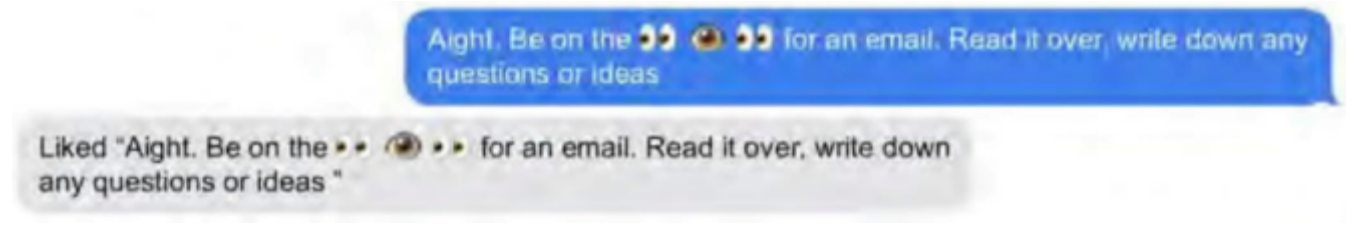

Modern Remodeling v. Tripod Holdings is instructive on this issue. In Modern Remodeling, the court found that a defendant (“Kimball”) selectively deleted relevant text messages he exchanged with his co-defendants as they were attempting to establish a company that would compete against plaintiff. The court determined that Kimball deleted relevant messages after finding the existence of “tapback” messages from his co-defendants even though the original message Kimball sent did not appear in the message string. The court provided an example of a “tapback” message (in grey below) and its corresponding original (in blue below) from Kimball that he had not eliminated:

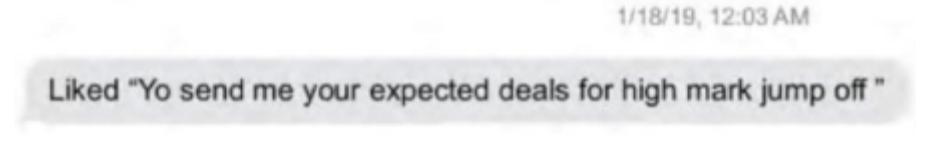

To demonstrate the contrast, the court displayed a “tapback” response where Kimball eliminated his original message:

The foregoing example was apparently representative of several other relevant messages that Kimball deleted, but for which he apparently neglected to eliminate the corresponding “tapback” message. The substance of the eliminated messages demonstrated that Kimball and other defendants were attempting to misappropriate plaintiff’s intellectual property or otherwise interfere with its business operations. The elimination of this evidence and other relevant information resulted in the court issuing a mandatory adverse inference instruction to the jury that Kimball intentionally deleted text messages which were unfavorable to him. In most cases where the court issues an adverse inference instruction against a party resulting from evidence spoliation, the jury generally finds against that party. The result in Modern Remodeling was no different, with the jury returning a verdict against Kimball (and his co-defendants) in this action.

iMessage’s “Automated Deletion” Feature – Paisley Park Enters., Inc. v. Boxill, 330 F.R.D. 226 (D. Minn. 2019); Nuvasive, Inc. v. Absolute Med., LLC, No. 6:17-CV-2206-CEM-GJK, 2021 WL 3008153 (M.D. Fla. May 4, 2021).

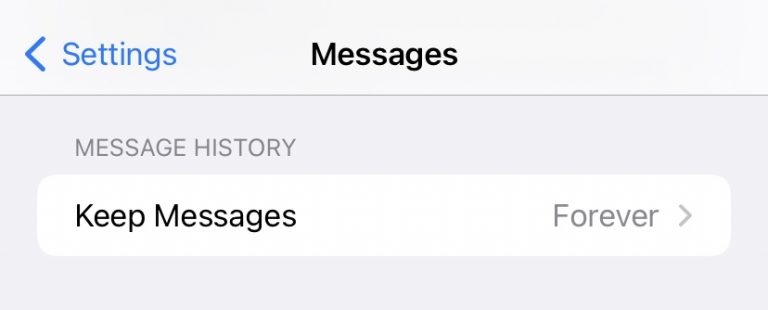

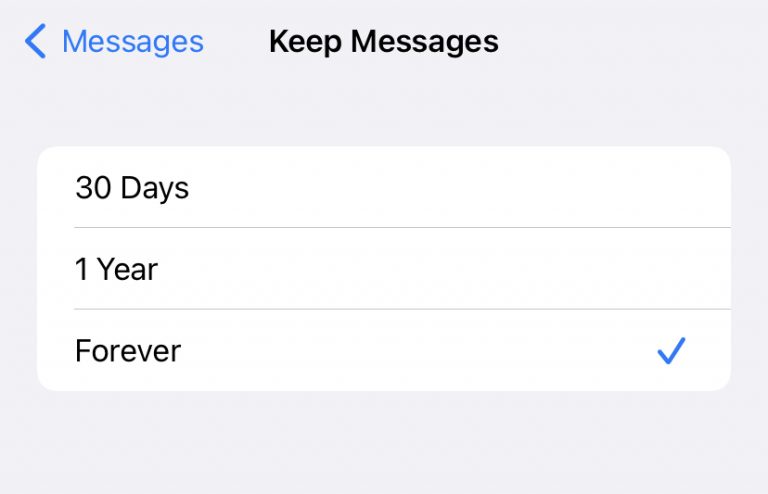

Certain Apple mobile device users are familiar with the iOS automated deletion feature that allows users to modify the retention of text messages (both iMessages and SMS messages) on their device. While Apple’s factory default setting is “Forever,” users may change that setting to retain messages for only 30 days or one year (depending on which preference is selected).

If an individual or organizational client employee has enabled the automated deletion feature for either time period, this may cause relevant information to be eliminated. This is precisely what transpired in Paisley Park Enterprises, Inc. v. Boxill, where the court imposed sanctions on defendants for failing to preserve relevant text messages on their smartphones. Among other things, defendants did not disable the user-enabled automated deletion feature on their iPhones after the court issued multiple orders requiring the parties to keep relevant text messages. Given the court’s preservation orders and the ease at which they could have reset the automated deletion feature to ensure messages would be kept “Forever,” defendants’ failure to do so was unreasonable and resulted in sanctions. See also Mod. Remodeling, Inc. v. Tripod Holdings, LLC, No. CV CCB-19-1397, 2021 WL 3852323 (D. Md. Aug. 27, 2021) (imposing sanctions on parties who failed to preserve relevant text messages because they neglected to disable the automated deletion feature on their iPhones).

Even though the automated deletion feature may cause messages to be eliminated, some parties have attempted to rely on the feature as a way of exculpating their deletion of messages, asserting it was “only a mistake” and does not merit severe sanctions. In several of these cases, courts have found that such an assertion cannot withstand scrutiny given other evidence suggesting the parties selectively eliminated certain text messages. Nuvasive, Inc. v. Absolute Medical, LLC is exemplary on this point. In Nuvasive, a defendant (Soufleris) argued that his text messages were eliminated as a result of his iPhone’s automated deletion feature. The court rejected this argument because evidence confirmed Soufleris selectively eliminated text messages during the six-month period leading up to the filing of the lawsuit: “[The] auto-delete function would delete all text messages prior to a certain date, not just messages within a timeframe crucial to the issues in this litigation.” The court found Soufleris’s selective deletion of messages evinced his intent to eliminate relevant evidence, which the court held warranted the issuance of an adverse inference instruction to the jury. See also Kixsports, LLC v. Munn, No. 17 CVS 16373, 2019 WL 4766249 (N.C. Super. Sept. 30, 2019) (“Pye’s smartphones contained thousands of messages from 2017 but none exchanged with Carr, even though it is undisputed that such messages once existed. This cannot be explained by a theory of automated deletion; it is strong evidence of selective deletion of messages between Pye and Carr.”).

Telegram’s Ephemeral Messaging Feature – Fast v. GoDaddy.com LLC, 340 F.R.D. 326 (D. Ariz. 2022).

Ephemeral messaging apps go a step beyond iMessage by automating the deletion of text messages on both the sender’s and the recipient’s devices after a short, preset time (30 seconds, 10 minutes, one hour, etc.). By so doing, ephemeral messaging apps can cause relevant evidence (messages, audio files, images, video files, and message metadata) to be functionally deleted (technically rendered inaccessible by eliminating the decryption key), which courts have found to merit the imposition of severe sanctions. Several cases over the past few years are exemplary on this point, particularly the aforementioned case of Fast v. GoDaddy.

In Fast, the court also imposed sanctions against plaintiff for improperly disposing of relevant messages from Telegram, an ephemeral messaging app. The court found that the circumstances surrounding plaintiff’s use of Telegram to communicate with Mudro suggested their messages would have reflected relevant, responsive information. For example, after plaintiff began using Telegram, plaintiff stopped exchanging messages with Mudro on Facebook Messenger (their preferred medium for communication) for five consecutive days. Nor were there Facebook Messenger messages between plaintiff and Mudro discussing the “stuff” plaintiff apparently indicated she wanted to share with Mudro over Telegram. Finally, no messages were ever found on plaintiff’s Telegram account. While plaintiff argued that the lack of messages (“no messages here yet”) suggested she never communicated with Mudro on Telegram, the court disagreed. In particular, the court spotlighted the automated deletion feature Telegram offers its users—“A hallmark of Telegram is that a user can delete sent and received messages for both parties”—and held that these collective details, supported by the testimony of defendant’s forensics expert, warranted the imposition of an adverse inference instruction at trial against plaintiff.

Fast represents a growing number of cases where courts have issued case determinative sanctions for a party’s use of ephemeral messaging that resulted in the deletion of relevant messages. See, e.g., F.T.C. v. Noland, No. 20-cv-00047-PHX-DWL, 2021 WL 3857413 (D. Ariz. Aug. 30, 2021) (imposing sanctions on defendants for failing to preserve relevant messages exchanged on Signal after the duty to preserve attached); WeRide Corp. v. Kun Huang, No. 5:18-cv-07233, 2020 WL 1967209 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 24, 2020) (holding that default judgment was a proper sanction against defendants for their elimination of relevant evidence from, among other locations, DingTalk, a workplace ephemeral messaging app made by Alibaba and popular in China with over 500 million users).

While courts have punished parties for using ephemeral messaging during litigation, there are generally no prohibitions (unless your company is regulated by the SEC) against using this method of communication outside of litigation. Indeed, ephemeral messaging offers many benefits for enterprises, particularly in the areas of information governance and compliance with data protection and privacy statutes. And yet, given the negative reactions that many reflexively experience toward ephemeral messaging—“Why do you need your messages to disappear? What are you trying to hide?”—organizations and individuals should carefully consider when and why they use ephemeral messaging to communicate.

Pingback: Preserving Text Messages | mtanenbaum()