Section 230 Doesn’t Apply to Publication of Private Emails–Crowley v. Faison

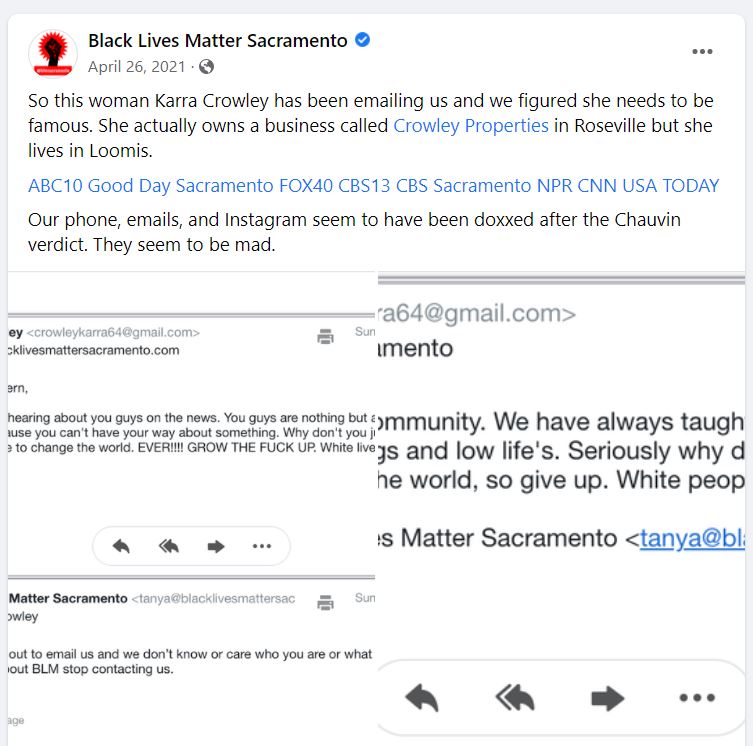

Faison runs the Sacramento chapter of Black Lives Matter (BLM). She received several racist and offensive emails from an email address purporting to be Karra Crowley. Faison posted the emails to BLM’s Facebook page and identified Karra as the sender.

Predictably, the blowback against Karra and her family/business was severe, including death threats. Months later, the sheriff apparently identified the actual sender, who wasn’t Karra. (Karra claims it’s a vengeful evicted tenant). Crowley sued Faison for defamation. Faison defended on Section 230 grounds. The court disagrees.

ICS User. Faison qualified as a Facebook user. A reminder that Section 230 applies to everyone connected to the Internet, including ordinary individuals. It’s not exclusively a tool for “Big Tech.”

ICS User. Faison qualified as a Facebook user. A reminder that Section 230 applies to everyone connected to the Internet, including ordinary individuals. It’s not exclusively a tool for “Big Tech.”

Provided by a Third-Party. The emails came from a third party, but this case raises a Batzel v. Smith issue. In that case, the Ninth Circuit said that republishing third-party emails would be protected by Section 230 only if the sender intended to have them published. The court cites three reasons why that’s not the case:

- The court says if the sender wanted the emails public, the sender could have posted them on the BLM Facebook page. Of course, Facebook posting would have made the impersonation hard or impossible, so it wasn’t a viable substitute for the emails.

- The actual Karra notified Faison that the emails were fake, yet Faison didn’t remove the Facebook posts. Normally, Section 230 doesn’t depend on whether the plaintiff sent takedown notices, but I think the court is implying that Faison should have known the emails weren’t meant for publication.

- Faison did more than just post the emails. Faison also encouraged readers to spread the word and claimed that the sender’s authenticity had been verified. The court says the defamation claim is based on those additional comments.

Sigh. The court could have made only that last point, i.e., that the plaintiff’s claim is based on Faison’s comments about the posted emails, not the email contents themselves. Or the court could have simply said that the emails were not meant to be published because nothing in the emails indicates that desire; plus the emails weren’t sent to a media outlet where everything is presumptively “on the record.” Instead, the court cluttered up what might have been a fairly simple and uncontroversial conclusion.

It’s impossible to miss the parallels between this case and the venerable Zeran v. AOL case. In the Zeran case, a malefactor posed as Zeran and posted grossly offensive fake ads on AOL that spurred a torrent of hate against Zeran, including death threats. More than 25 years after the cyberattack on Zeran, imposter attacks still succeed. Knowing the ease of online impersonation, any email recipient needs to sufficiently diligence the sender’s identity before publicly sharing inflammatory material.

Case citation: Crowley v. Faison, 2022 WL 624949 (E.D. Cal. March 3, 2022)