There Are Multiple Types of “Clickwrap.” They Should All Be Enforceable–Calderon v. Sixt

This case involves rental car contracts. Typically, a rental car company can form a contract at three different times: when making an online reservation, when actually completing the reservation in person (nowadays, usually it’s an electronic signature on a point-of-sale device), and through adhesive terms in the printed paperwork (what the court calls a “rental jacket”–a sartorial complement to a wrap, I guess). In this case, the plaintiffs are suing over allegedly undisclosed fees added on to the damages allegedly caused by renters. The rental car company, Sixt, invoked an arbitration clause.

(Tip: credit cards often provide insurance to cover these damage claims by rental car companies. I used it successfully when I got a windshield crack on a recent vacation. The tendering process worked quite smoothly and insurance paid everything, so I didn’t care what ridiculous fees the rental car company might have buried into the damages estimate. Unfortunately, my primary credit card has canceled this insurance coverage, so now I have to choose another card for my rental car bookings. Of course, there’s been no urgency for this during the pandemic shutdown).

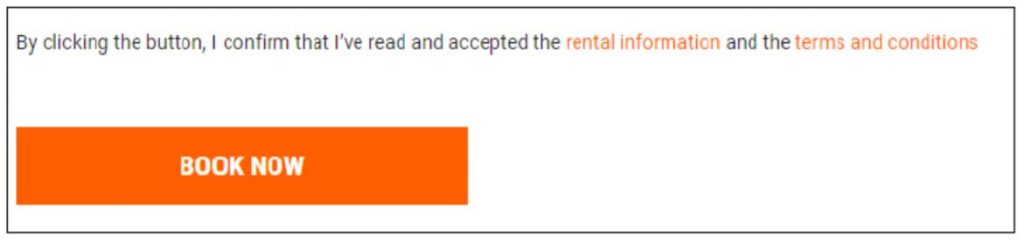

It appears the dispositive contract formation process occurred through the online reservation booking process, which included this mandatory screen:

The court says this “online booking process involves a modified or hybrid clickwrap agreement.” As I’ve told you before, the online contract formation field is overrun by junk terminology, including the fact that a “clickwrap” (what the court calls a “pure” clickwrap) could be a “modified or hybrid” clickwrap. FFS. Personally, I think Sixt used a “sign-in wrap,” but who am I to quibble with the wrap characterizations when I want to burn all of them to a crisp?

[Jargon watch: I checked in Westlaw this morning and there are 16 case references to “modified clickwrap” and 13 to “pure clickwrap.” 🤔]

The court says this formation process works because “Sixt’s website contained an ‘explicit textual notice’ that clicking the “BOOK NOW” button would manifest Charnis’s intent to be bound by Sixt’s Rental Jacket, including the arbitration provision.” The court could have, and should have, said this without getting into any of the wrap garbage.

The court also addresses the evidence Sixt introduced to demonstrate formation. This was on a motion to compel arbitration, not a motion to dismiss, so Sixt could provide evidence and the court evaluates it like on summary judgment. Sixt’s key evidence comes from a declaration from Dennis Boehringer, its director of corporate development. Boehringer claimed personal knowledge of the reservation booking process and that he had personally made some test reservations at the relevant time period. The court says this is good enough:

Boehringer manages projects for Sixt and tests the reservation process himself for those projects. He personally made reservations on Sixt’s website on November 11 and 25, 2019—around the same time as Charnis—and attests that the current website layout and booking process is the same as it was back then. The screenshot in Boehringer’s declaration shows that, by clicking the “BOOK NOW” button to complete the booking, customers confirm that they have read and accept the “terms and conditions.” Clicking the “terms and conditions” hyperlink sends the customer to the general “Terms and Conditions Rental Jacket,” a copy of which Boehringer attached to his declaration; that version was in effect in November 2019 and contains an arbitration provision.

The plaintiff didn’t introduce sufficient contrary evidence. “For example, Charnis does not assert that the layout of Sixt’s website was not as Boehringer described or that he did not actually click the ‘BOOK NOW’ button.”

Your periodic reminder: having a strong contract formation process is good; having credible evidence to convince the judge of that process without a fact trial is priceless.

Case citation: Calderon v. Sixt Rent a Car, LLC, 2021 WL 1325868 (S.D. Fla. April 9, 2021)