My California Young Lawyers Association Interview About Emojis

[In August, I did an interview with Skyler Gray that ran in the California Young Lawyers Association newsletter.]

How did an intersection of emojis and the law begin? Were there legal issues concerning the original punctuation emojis, such as “:)” or “:-)”?

The first time a U.S. court opinion referenced emoticons was in 2004. Emoticons have been referenced in dozens of cases since (though sometimes courts imprecisely characterize emojis as emoticons). The first time a U.S. court referenced emojis was in 2014.

What are the common types of cases that interpretation of emojis comes into play? Criminal? Civil? Or a mix of both?

The most common emoji case involves sexual predation of children. Other common cases include murder, discrimination, and harassment. Emojis tend to appear in opinions dealing with online conversation transcripts as evidence. For example, sexual predation prosecutions often include an online conversation between the victim and the defendant as part of the grooming process. Emojis crop up in these conversations.

Do you think there will be a time when online legal databases can search based on emoji?

Yes, but we are so far away from that. First, judges need to depict emojis in their opinions. Second, the database needs to include the visual images in its index. Third, the search mechanism needs to recognize emojis as valid search queries and be able to process such queries against its index. All of this is technically feasible today, but I haven’t seen a lot of motivation yet on the part of judges or legal databases to address these issues.

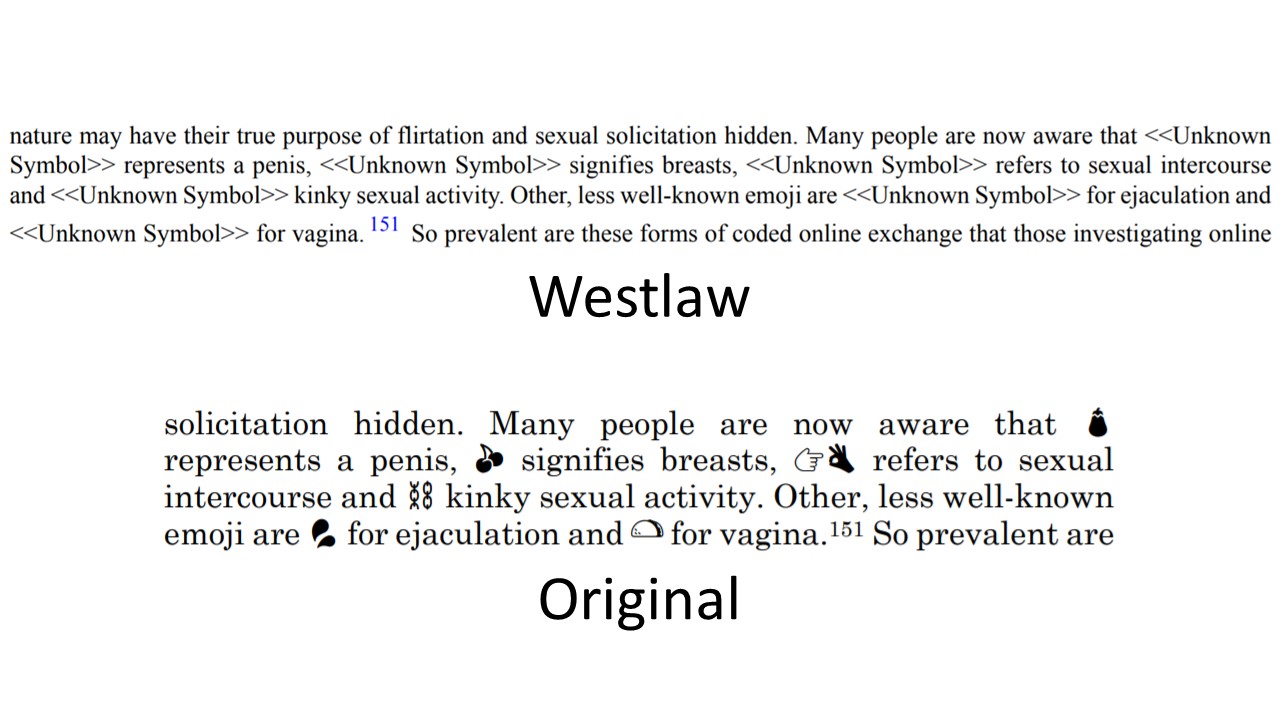

[Bonus: here’s a sample of how Westlaw currently handles emojis today:]

What is the highest court that has dealt with the interpretation of emojis? Are there any precedents as to the meaning of a particular emoji?

The U.S. Supreme Court dealt with a case partially involving emojis (Elonis v. US), but its opinion didn’t discuss the emojis. Numerous federal appellate courts and state supreme courts have discussed emojis. One recent example is an opinion from the Colorado Supreme Court, where the court held that emojis helped a teen avoid jailtime.

Dozens of cases have interpreted the meaning of individual emojis. As just one example, a court interpreted the specific meaning of the “crown” emoji in the sex trafficking community.

What inspired you to conduct research on discussion of emojis in legal cases?

I typically read 100+ cases a week, and sometimes I see something unusual that I don’t recall seeing before. In those circumstances, I may be curious how often that phenomenon has happened before. So when I saw a reference to “emoticon” in an opinion in 2016, I wondered how often emoticons had appeared in court opinions previously. All of the subsequent research questions naturally flowed from there.

Situational question: Let’s say an attorney is referencing a prior text message record of a witness in a criminal matter while that witness is on the stand. How does this work if a text contains an emoji? Does the attorney ask the judge to take judicial notice of the emoji?

Emojis can raise tricky issues in trial. The emoji needs to be properly introduced in evidence. That includes making sure that the visual depiction accurately reflects what the sender and recipient(s) actually saw. Then, it needs to be presented to the fact-finder. In circumstances where the evidence is being discussed orally in court–such as, say, your cross-examination example–how can the evidence be properly referenced? In the Silk Road trial, in this situation the prosecutor simply omitted references to the emoticons when recounting evidence. The defense counsel successfully objected, and the prosecutor had to orally characterize the emoticon. In those circumstances, I think visual depictions of the evidence, including the emojis, would be more helpful to the factfinder.

How does the First Amendment and free speech interact with an individual’s use of emojis?

Emojis need to be accorded full weight when interpreting online conversations. An emoji can flip the meaning of textual statements, or create a context indicating that the remarks should not be taken seriously. This can easily support First Amendment defenses, such as when an emoji indicates that seemingly threatening remarks are, in fact, meant to be interpreted facetiously or that the entire conversation is joking and thus aren’t legally actionable.

More generally, emojis support free expression by expanding our communication toolkit. They fill in gaps with other communicative options, helping us express ourselves more fully or precisely.

Have you ever testified in a case as an “emoji expert”? Is there such a thing and what are the common qualifications of an emoji expert?

I haven’t been an emoji expert yet, but one can dream 😍. Courts have occasionally introduced expert testimony to interpret emojis, but typically these are experts from the community, not linguistics or communications experts. For example, in the crown emoji/sex trafficking case, a law enforcement officer testified about his understanding of the slang in that community.

What advice do you have for new attorneys who want to get involved in cutting-edge technological issues?

It’s actually surprisingly easy to become a trusted specialist in new technological issues, even as a junior attorney. At minimum, the attorney needs to keep up with both the technical and legal literatures on the topic. Better yet, the attorney tracks new developments that other people aren’t seeing, and then evangelizes and interprets these new developments to the community. For example, to keep up with emojis, I have keyword alerts set up in Lexis and Westlaw, and I read every new opinion discussing them. I then blog interesting new developments in the caselaw when I see them. Any junior attorney could replicate this process for any emerging technology.