Court Upholds Gaming App’s Clickthrough TOS–Ball v. Skillz

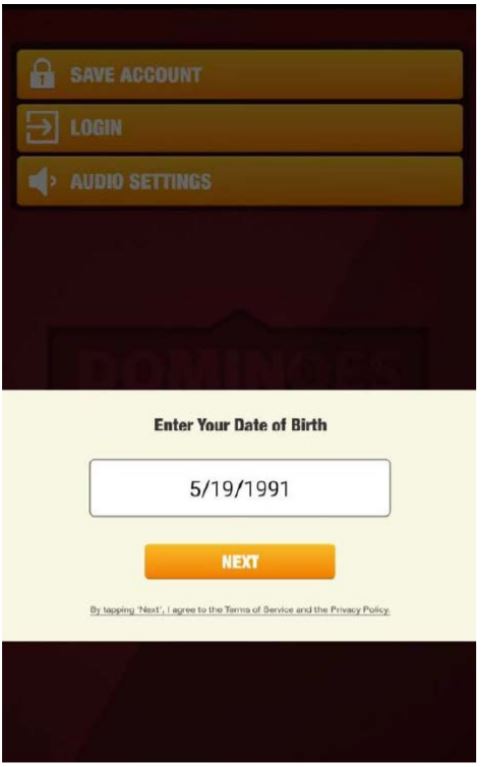

Skillz’s app 21 Blitz allowed players to play blackjack against each other. To sign up for the app, players had to navigate the following screen:

The linked TOS contained a prominent arbitration clause. Two plaintiffs sued Skillz for locking them out of their accounts, apparently impounding significant winnings. Another plaintiff sued after significant losses, claiming the app fueled a gambling addiction. Skillz moved to send the case to arbitration. The court agreed.

The screenshot above depicts a fairly straightforward old-school clickthrough agreement. The court does the standard recitation of “clickwrap” and “browsewrap” definitions and, as usual, says they don’t apply: “The Skillz agreement falls somewhere between browsewrap and clickwrap: users do not have to take an extra step to acknowledge the agreement before creating their accounts, but Skillz does not attempt to bind users with a passive statement about the existence of the terms either.” (This is what the Berkson case called a “sign-in-wrap,” but fortunately the court doesn’t dignify that term by using it).

The court says the call-to-action is sufficiently visible due to its contrasting color. Thus, the TOS is enforceable. The court surprisingly doesn’t take issue with the small font, which was not kind to my aging eyes.

The plaintiffs argued that only “pure clickwrap” agreements are enforceable. (Those of you familiar with my animosity towards the “-wrap” nomenclature can imagine my reaction to seeing the term “pure clickwrap”: 🤯). The court says a second click is nice but not required:

Just because courts approved one method of obtaining assent to online agreements does not mean that any other method is invalid. While an additional step would provide additional notice to users that there were consequences to signing up for a Skillz account, plaintiffs have not shown that the law required that step.

The court also rejects an unconscionability challenge. The TOS is a contract of adhesion. The contract also required the plaintiffs to split arbitration fees and costs, which the court says would be substantively unconscionable. However, the court invokes the severability clause to excise that term, leaving the rest of the arbitration clause intact.

Though Skillz got the outcome it wanted, it had some obvious opportunities for improvement:

- Bigger font size for the call-to-action. As I’ve said before, the call-to-action’s font size should never be the smallest font size on the page.

- A second click would have been trivially easy to add and would have functionally eliminated the formation challenge.

- Polish up the substantive arbitration terms to remove any risky terms. Who bears the costs of arbitration is a tricky issue to navigate. The vendor should bear the costs to make it comparable to litigating in court, but recall that plaintiffs have also weaponized that cost-shifting provision.

Case citation: Ball v. Skillz Inc., 2020 WL 6685514 (D. Nev. Nov. 12, 2020) [I love this case caption]

Pingback: News of the Week; November 18, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall()