Ninth Circuit Doubles Down on Bad Ruling That Undermines Cybersecurity–Enigma v. Malwarebytes

This PUP Is definitely having a bad day after this ruling.

photo by Anik Shrestha, https://www.flickr.com/photos/anikshrestha/

This case involves rival makers of anti-threat software. The defendant, Malwarebytes, classified its rival’s software as a PUP, or Potentially Unwanted Program. The rival sued. Malwarebytes defended on 47 USC 230(c)(2)(B), which provides a safe harbor for filtering software. Malwarebytes won on that ground in the district court. Then, in a troubling ruling that broke with precedent, a 3-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit held that (1) 230(c)(2)(B) requires good faith on the part of filtering software makers, and (2) mere allegations that filtering was based on ant-competitive animus defeat the 230(c)(2)(B) safe harbor. Thus, Malwarebytes cannot rely on the safe harbor that Congress custom-developed for this circumstance.

Malwarebytes sought rehearings by the panel and en banc. In support of that request, Venkat and I, on behalf of 7 other cybersecurity law professors, submitted an amicus brief explaining how the ruling undermined cybersecurity, because it will discourage anti-threat software makers from legitimately downgrading their shady AF rivals (and many anti-threat software vendors are indeed shady AF). Any benefits consumers might gain from policing anticompetitive downgrades surely will be overwhelmed by the greater proliferation of harmful software that undermines our online security.

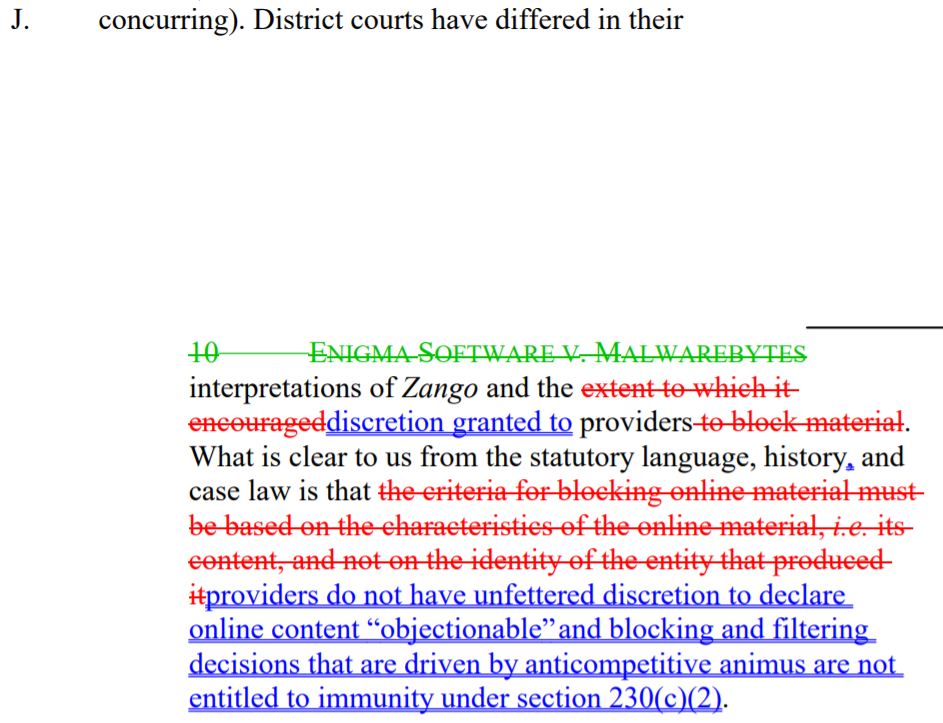

On New Years Eve (in a fitting end to an awful year for Internet Law), the Ninth Circuit denied the petition and issued an amended opinion. Unfortunately, the court made only minor substantive amendments. The redline of those substantive changes:

There are two good aspects of this amended opinion. First, the court got rid of the murky language that filtering software makers could not consider the identity of the threat’s maker in its filtering decision. That legal standard contravened central tenets of cybersecurity, so good riddance. Second, the amended language expresses the court’s holding exceptionally clearly: “blocking and filtering decisions that are driven by anticompetitive animus are not entitled to immunity under section 230(c)(2).”

I have nothing else good to say about the amendments. The court still collapses 230(c)(2)(A), which has a “good faith” requirement, with 230(c)(2)(B), which does not; and the amended opinion still gives purveyors of shady AF anti-threat software an easy workaround to any future 230(c)(2)(B) defense. For reasons that Venkat and I explain in the amicus brief, this makes the Internet less secure.

As for this case, Malwarebytes has a choice. It can appeal to the US Supreme Court, which I personally hope it does not do because the case’s legal issues aren’t the best fact setup for SCOTUS review of Section 230. Malwarebytes would have favorable odds on appeal, but the odds of something going dreadfully wrong are too high for my tastes. Alternatively, Malwarebytes can pursue the case on remand and win on the merits. Rebecca Tushnet explores some of the likely arguments. On remand, Malwarebytes probably will show that its filtering decision lacked anti-competitive animus, in which case it deserved the Section 230(c)(2)(B) safe harbor that this court denied. That wouldn’t be the first time that the Ninth Circuit eviscerated Section 230’s procedural benefits for no corresponding gains. Recall, for example, how the court denied Section 230 for Roommates.com because it allegedly engaged in illegal content, only to conclude four years later that Roommates.com actually qualified for Section 230 all along because Roommates.com never had illegal content at all.

Case citation: Enigma Software Group USA v. Malwarebytes, Inc., 2019 WL 7373959 (9th Cir. Dec. 31, 2019)

Case library:

- Malwarebytes’ petition for rehearing. Supporting amicus briefs from cybersecurity law professors, EFF/CAUCE, ESET, and Internet Association. Blog post on the filings.

- Ninth Circuit ruling. Blog post on that ruling.

- District court opinion. Blog post on that ruling.

- Related decision in Enigma Software v. Bleeping Computer. Blog post on that ruling.

Pingback: News of the Week; January 15, 2020 – Communications Law at Allard Hall()