Internet Access Provider May Be Vicariously Liable for Subscribers’ BitTorrent Downloads–Warner Bros. v. Charter

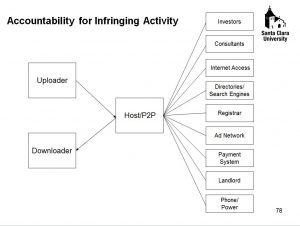

This is another copyright infringement lawsuit against an Internet access provider for subscribers’ allegedly infringing P2P file sharing activity. It extends the copyright owners’ successes in two similar lawsuits, BMG v. Cox and UMG v. Grande. In this ruling, the IAP sought to dismiss the vicarious copyright infringement claim. The judge rejects the motion, issuing an opinion that–if it stands–will be a major win for copyright owners in their irrepressible quest to deputize IAPs as their copyright sheriffs.

This is another copyright infringement lawsuit against an Internet access provider for subscribers’ allegedly infringing P2P file sharing activity. It extends the copyright owners’ successes in two similar lawsuits, BMG v. Cox and UMG v. Grande. In this ruling, the IAP sought to dismiss the vicarious copyright infringement claim. The judge rejects the motion, issuing an opinion that–if it stands–will be a major win for copyright owners in their irrepressible quest to deputize IAPs as their copyright sheriffs.

The Vicarious Copyright Infringement Ruling

The venerable test for vicarious copyright infringement is when the defendant (1) had the right and ability to supervise the infringer’s acts, and (2) had a direct financial interest in those acts. For unknown reasons, in Grokster, the US Supreme Court rearticulated the test as “profiting from direct infringement while declining to exercise a right to stop or limit it.” Since then, courts have split about which test to use. Some courts stick with the classic test; others use the Grokster rearticulation. In many cases, the two tests will lead to the same result, but this case highlights how the Grokster rearticulation may be more plaintiff-favorable. The judge explained why the motion to dismiss failed:

Direct Financial Interest.

The plaintiffs properly alleged the IAP had a direct financial interest in subscriber-committed copyright infringement with the following allegations:

Defendant’s subscribers are “motivated” by company advertisements promoting Defendant’s “high speed” service that “enables subscribers to … ‘download 8 songs in 3 seconds’”; Defendant’s subscribers have used such service to “pirate” Plaintiffs’ works, as evidenced by Plaintiffs’ identification between 2012 and 2015 of “hundreds of thousands” of instances in which Defendant’s subscribers used its service to distribute Plaintiffs’ songs illegally; despite notification of its subscribers’ infringement, Defendant did nothing to stop it; once Defendant’s subscribers realized that Defendant did not intend to stop or control the infringement, they “purchased more bandwidth” and continued using Defendant’s service to infringe Plaintiffs’ copyrights; and, the greater the bandwidth used for pirating content, “the more money [Defendant] made.”

Right and Ability to Supervise

The plaintiffs properly alleged the IAP had a right and ability to supervise its subscribers’ alleged copyright infringement with the following allegations:

Defendant’s own “Terms of Service/Policies” expressly prohibits users from engaging in copyright infringement and reserves to Defendant the right to terminate users’ accounts for participating in piracy. Plaintiffs provided Defendant with “hundreds of thousands” of notices of infringement; yet, despite the notices identifying the infringing users and the Defendant’s policy, Defendant failed to stop or limit the infringement by suspending or terminating these users’ accounts.

Implications

The Possible Irrelevance of 512(a). The DMCA was supposed to resolve IAPs’ liability for subscriber-caused copyright infringement. Section 512(a) eliminates damages and limits injunctions for “transmitting, routing, or providing connections for, material through a system or network controlled or operated by or for the service provider.” Unlike the more commonly litigated 512(c) safe harbor for web hosting, there is no notice-and-takedown predicate for 512(a); and 512(a) seemingly applies equally to direct, contributory, and vicarious infringement claims. For this reason, for the first ~15 years after the DMCA’s passage, copyright owners largely ignored IAPs as defendants. Obviously, that detente has broken down.

This opinion didn’t cite 512(a) at all because the IAP didn’t push it yet. Instead, the IAP thought it could get a quick win on the prima facie elements. Still, the fact the IAP isn’t making 512(a) the centerpiece of its defense is a warning sign about 512(a)’s utility. In BMG v. Cox, the court held that copyright owners could work around 512(a) if they could show that the IAP hadn’t done enough to terminate repeat infringers. Reviewing how an IAP handles repeat infringers necessarily makes a 512(a) defense factually intensive–the kind of thing that usually doesn’t support a motion to dismiss.

The IAP can still invoke 512(a), and I expect it will. But this ruling shows how the defense costs to IAPs has implicitly increased over time–from a situation where IAPs were never sued, to now a situation where IAPs can’t win motions to dismiss and must proceed to summary judgment or beyond.

The Detritus of the Copyright Alert System’s Demise. In 2011, major copyright owners and IAPs struck a deal called the Copyright Alert System, sometimes called the “6 strikes” program. The deal basically deputized IAPs to be copyright sheriffs. Copyright owners could send notices of claimed P2P infringement about an IAP’s subscribers, and the IAP would treat each notice as a “strike” that led to progressively stiffer discipline of the subscriber. The IAPs’ willingness to participate in the system was baffling, because 512(a) should have mooted their need to help copyright owners. Meanwhile, it was an even worse deal for consumers, who were being penalized based on claims that may have been bogus and that were hard to challenge.

Despite the fanfare associated with its launch, the Copyright Alert System imploded in 2017. The URL now rolls over to mattress[.]net. 💣💣💣

The demise of the Copyright Alert System sounded like good news, but now I’m wondering if it will lead to an even worse outcome. As bad as the system was, at least the copyright owners weren’t suing IAPs. Now, without the Copyright Alert System, copyright owners apparently have taken the litigation gloves off. Worse, by hammering what constitutes a “repeat infringer,” the copyright owners are basically forcing the IAPs to treat every notice of claimed infringement as legitimate, something that wasn’t mandatory in the Copyright Alert System. If the courts don’t shut down this litigation vector, it looks like copyright owners may successfully force IAPs to do more policing work that even the failed Copyright Alert System required.

What is “Direct Financial Interest”? The caselaw has been clear for years that monthly subscription fees do not constitute “direct financial interest” in infringement because they do not increase or decrease with the quantum of infringing activity. This judge nevertheless ruled against the IAP because the subscribers’ opportunity to infringe acts as a “draw” (going back to the old 9th Circuit Fonovisa language) to subscribe. This, of course, is garbage, and it should fail on summary judgment because the copyright owners should have trouble marshaling credible evidence backing up the claim. It’s especially galling that the court credited the IAP’s marketing (“download 8 songs in 3 seconds”) against the IAP. The court assumes that fast song downloads are only infringing….because? (Then again, I always feared Apple’s “Rip. Mix. Burn.” tagline would lead to this kind of problem). There are so many freely downloadable songs on the Internet now; why should the judge assume the marketing only appeals to infringers?

What is “Right and Ability to Supervise”? Relying on the troublesome Grokster rearticulation of the test, the court turns vicarious infringement into a glorified notice-and-takedown scheme. The court said that the IAP got notices about problematic subscribers and failed to terminate their accounts–i.e., notice-and-takedown, but with a massive twist. Instead of taking down an individual item of content, the copyright owners are demanding that the subscriber’s Internet access be terminated. That remedy is a major mismatch to the purported violation. Internet access is widely viewed as a fundamental human right in the modern era, and the copyright owners are demanding termination of the account in response to unverified assertions of copyright infringement.

The fact that this court converts vicarious copyright law into a “notice-and-takedown” scheme–the sort of thing ordinarily pertinent to contributory copyright infringement–shows how distinctions between vicarious and contributory liability have essentially collapsed online. As the Supreme Court said in Sony v. Universal City case, “the lines between direct infringement, contributory infringement and vicarious liability are not clearly drawn.” This case essentially obliterates those lines. Contributory copyright infringement normally requires scienter; direct and vicarious infringement normally don’t. Conflating contributory and vicarious infringement creates a real risk that courts will extend the zones where scienter isn’t required for liability.

More generally, IAPs lack the ability to “supervise” their subscribers’ activities at all. Unless the IAPs are doing deep packet inspection–which many people would consider to be a major privacy violation–then IAPs don’t really know what their subscribers are doing. Sure, the IAPs can review the metadata of subscribers’ activity, and that might suggest illicit behavior. Otherwise, IAPs are supposed to be passive conduits/tubes to agnostically move data between subscribers and third parties. Given IAPs’ non-interventionist role in the Internet “stack,” IAPs categorically should lack supervisory power over their subscribers.

IAPs as Preferred Tools of Censors. Another place where IAPs are deputized to police content: repressive and censorious regimes. So the copyright owners are embracing the same content control techniques as dictators. 👎👎👎

Conclusion

It’s always been clear that IAPs should not act as copyright cops, similar to how other utilities like telephone or power companies are in a terrible position to curb illegal usages of their services. IAPs are in a good position to move data. They are not in a good position to become content censors. Further, IAPs have a limited remedy toolkit–turning service on or off–that leads to remedies disproportionate to the violation. Finally, Internet access is so essential to everyday life that it should not be subject to sanctions imposed extrajudicially. That’s why 512(a) was so clear that IAPs aren’t a proper defendant for secondary copyright infringement.

Still, copyright owners aren’t going to stop until they turn IAPs into their copyright cops. This has their dream for decades, and this ruling moves one step closer to it.

To be clear, much of the damage in this case was done by the Cox and Grande litigation. That’s how copyright owners undermine a statutory deal like the DMCA. They start with test cases, then they put extra pressure on any cracks exposed in the trial balloons. This case extends the prior rulings and highlights the copyright owners’ end game. They seek to use the courts to force IAPs to implement a more copyright owner-friendly system than the Copyright Alert System. This ruling shows they are well on their way to achieving that.

Case Citation: Warner Bros. Records Inc. v . Charter Communications, Inc., 1:19-cv-00874-RBJ-MEH (D. Colo. Oct. 21, 2019)

Some Related Posts:

- Recap of the Copyright Office’s Section 512 Study Roundtable

- Court Blasts “Copyright Troll” for Treating Courts “as an ATM”–Strike 3 v. Doe

- 512(h) Doesn’t Preempt Doe Unmasking Lawsuits–Strike 3 v. Doe

- IP Address Subscriber Isn’t Liable for Copyright Infringement by Users Sharing That IP Address–Cobbler v. Gonzales

- Are Internet Access Providers Liable for Their Subscribers’ Copyright Infringements?–UMG v. Grande

- Cox Loses DMCA Safe Harbor but Gets a New Trial on Contributory Infringement–BMG v. Cox

- Before Graduated Response, There Was BSA’s “Define the Line” Program. What Happened to It? (Guest Blog Post)

- Six-Month Retrospective of SOPA’s Demise [Forbes Cross-Post, A Month Late!] + SOPA/PROTECT-IP/OPEN Linkwrap #3

- Why I Oppose the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA)/E-PARASITES Act

- The “Graduated Response” Deal: What if Users Had Been At the Table? (Co-Authored Post)

Pingback: Internet Access Provider May Be Vicariously Liable for Subscribers’ BitTorrent Downloads – RightsTech Project()

Pingback: Strike 3's Copyright Litigation Campaign Completely Strikes Out - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()