Are Internet Access Providers Liable for Their Subscribers’ Copyright Infringements?–UMG v. Grande

By 2018, you’d think it would be clear when Internet access providers (I HATE the term “ISP”) are liable for user-committed copyright infringements. After all, the 1995 Netcom case discussed Netcom’s functions as an IAP, and the DMCA in 1998 codified aspects of Netcom and included the 512(a) safe harbor specifically protecting IAPs. Furthermore, some IAPs “voluntarily” adopted the “Copyright Alert System,” a six-strikes system based on incidents of P2P copyright infringement, and you’d think that would satisfy the copyright owners (though the CAS failed, as expected).

Yet, here we are, still wrangling with this question 20+ years later. Indeed, last month’s troubling BMG v. Cox decision showed how many questions remain unanswered about IAPs’ liability for user-caused copyright infringement.

Grande is an IAP which has, like all IAPs, BitTorrent-using subscribers. UMG claims its DMCA agent, Rightscorp, sent millions of takedown notices to Grande, and Grande didn’t cut off service to these infringers. (As you may recall in the BMG case, Rightscorp’s voluminous robo-notifications were so frequently dubious that Cox categorically ignored them). UMG sued Grande for secondary copyright infringement. For kicks, UMG also sued Patriot, a management consulting firm, for allegedly “formulating and implementing the business policies, procedures, and practices that provide repeat infringers with continued internet service through Grande.” Both Grande and Patriot moved to dismiss. The court grants Patriot’s motion and part of Grande’s motion.

Direct Infringement. The complaint merely recites how Rightscorp’s notification system works, so it does not enumerate any specific act of infringement of a specific work by a specific Grande subscriber. Still, the court says that UMG provided enough “circumstantial evidence of copying” to satisfy the pleading requirement because everyone apparently agrees that some subscribers “made available” copyrighted works via BitTorrent, and the court doesn’t want to resolve whether “making available” constitutes a “distribution” at this stage of the litigation.

Sony Rule. Grande claimed that Sony’s “staple article of commerce” doctrine protected it because its services are capable of substantial non-infringing uses. Citing the BMG ruling, the court says “this is not yet a well-defined area of the law” but it wasn’t going to dismiss the case now because “the Court is persuaded that UMG has pled a plausible claim of secondary infringement based on Grande’s alleged failure to act when presented with evidence of ongoing, pervasive infringement by its subscribers.” This is an example of how Grokster turned Sony into an evidentiary rule that plaintiffs can plead around; and the BMG case reinforced how Sony offers limited protection to Internet services. (Though the BMG court said that general knowledge of infringement wasn’t enough to plead around Sony; the plaintiff had to plead specific acts of infringement, which I wonder if the plaintiff’s “circumstantial evidence” failed to do).

Vicarious Infringement. The court says “Grande can stop or limit the infringing conduct by terminating its subscribers’ internet access.” That’s a true statement, but perhaps a little tone-deaf. Terminating Internet access has far more consequences for the subscriber than just cutting off BitTorrent access. Still, this turns out to be a moot segue. Grande charges a flat monthly subscription fee, and most courts have held that isn’t direct financial benefit from infringing activity. UMG also tried the specious argument that music is a draw for Internet access, and the court rightly says that argument would sweep in all IAPs. Thus, the court dismisses the vicarious copyright infringement claim.

Tertiary Liability. Patriot says UMG is trying to hold it tertiarily liable for subscribers’ copyright infringement. In response, UMG cited UMG v. Bertlesmann and argued:

Patriot affirmatively performs executive, general counsel, and management functions for Grande, and thus is directly involved in the actions and inactions of Grande that gave rise to the infringement. UMG maintains that Patriot formulates and implements the policies and practices as to how Grande responds, or fails to respond, to notices of infringing activity.

The court responds that the complaint was deficient:

nowhere does the Complaint allege that Patriot itself, as an entity, was involved in the decisions or actions on which UMG bases its claim. Instead, it only alleges that employees of Patriot, who were also employees of Grande, may have assisted in formulating Grande’s policies in dealing with the underlying infringement as issue here….Thus, whatever decisions Grande made that might impose liability on it, they were made by Grande, not Patriot. UMG’s claims against Patriot are a very poorly disguised attempt to ignore Grande’s corporate form, and to impose liability on Patriot solely because it provides services to Grande. The relationship between the alleged direct infringers and Patriot is too attenuated to support a claim against Patriot.

Thus, Patriot is dismissed from the suit with prejudice.

Implications

Virtually every IAP allows subscribers to use BitTorrent. This case is a direct assault on that practice. If it succeeds, it would require IAPs to categorically turn off BitTorrent somehow; or to terminate subscribers who use BitTorrent based on unsubstantiated DMCA notices from a robo-notice outfit like Rightscorp. Thus, this lawsuit’s objectives seem to go far beyond the already decrepit policies of the Copyright Alert System, which had a 6 strike mechanism that did not necessarily require account termination on the 6th strike.

For reasons that aren’t clear to me, 512(a) doesn’t get mentioned at all. That is disappointing, because 512(a) was supposed to have resolved this issue in the IAPs’ favor. Without 512(a) protection, IAPs face industry-ending liability for copyright infringement by their subscribers. I don’t see how a plaintiff win here ends without severe repercussions for all IAPs. See this article for more on the withering of the DMCA safe harbors.

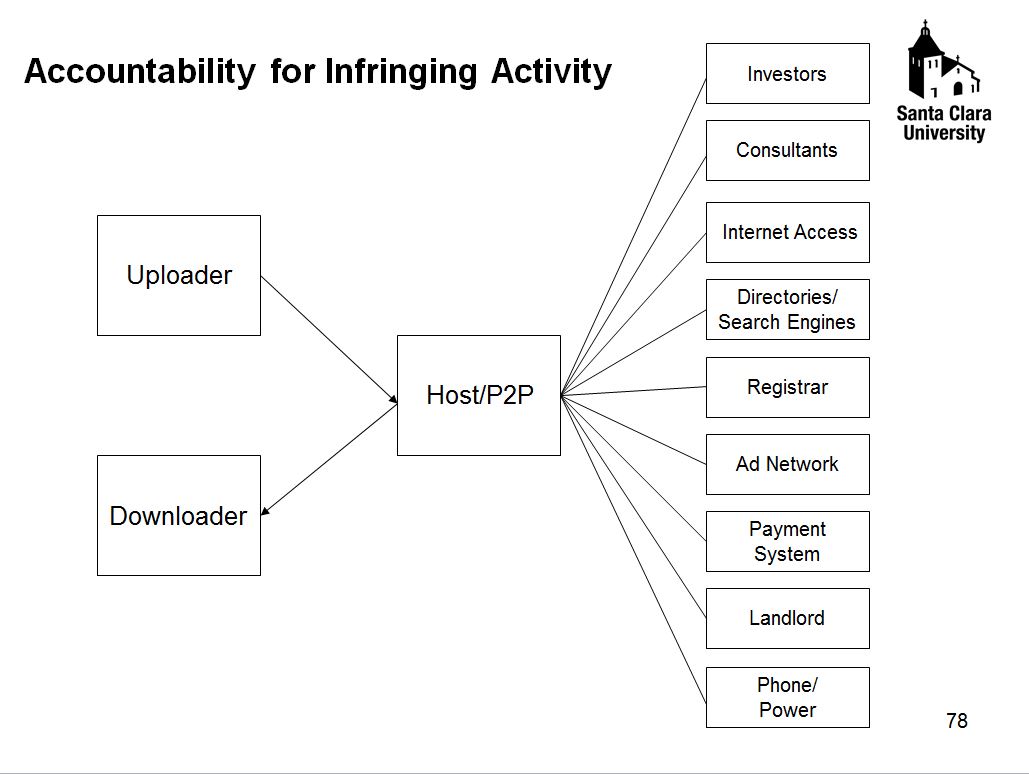

More generally, this case reminds us that copyright owners are still suing many other defendants beyond the direct infringer(s) to deputize increasingly distant players as copyright cops. After SOPA/PIPA, I put together this slide that shows the range of potential defendants. Online copyright litigation has increasingly migrated from the left side defendants to the right side defendants:

As this case illustrates, UMG is still chasing defendants (including “consultants”) on the right side on tertiary liability grounds. They will keep doing so until we fix the safe harbors or underlying doctrines to shut down such overreaches. This is one of the reasons why the legislative flameout of SOPA/PIPA did not really resolve the underlying policy issues.

Case citation: UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Grande Communications Networks, LLC, 2018 WL 1096871 (W.D. Tex. Feb. 28, 2018). This is a magistrate R&R, so it’s possible the supervising judge will do something different.