2H 2018 Quick Links, Part 4 (Trespass, Contracts)

Trespass

* Ryanair v. Expedia, 2018 WL 3727599 (W.D. Wash. Aug. 6, 2018). CFAA can apply when a US company scrapes data from an international website.

* Jackie’s Enterprises, Inc. v. Belleville 2018 N.Y. Slip Op. 07225 (N.Y. App. Div. Oct. 25, 2018):

Generally, the factual allegations underlying plaintiff’s trespass to chattels and/or conversion claim are that defendants unlawfully canceled shipments of goods, attempted to divert goods, supplies and mail from plaintiff’s possession, unlawfully accessed plaintiff’s Facebook and Yelp! online accounts and web pages and unlawfully attempted to gain access to and control of plaintiff’s credit card processing service account. Assuming that a cause of action for trespass or conversion even applies to intangible items such as websites, as noted above, plaintiff had no possessory interest in the online accounts and web pages because the seizure order permitted Belleville to lawfully gain control of them. Additionally, defendants did not actually interfere with plaintiff’s control of the credit card processing service account. Regarding orders and deliveries, plaintiff was required to point to “specific identifiable” property that defendants interfered with or over which defendants allegedly exercised control. Setting aside general allegations in the complaint and Keto’s affidavit, plaintiff only specifically referred to defendants interfering with deliveries from one particular supplier, but Keto averred that she ultimately received the delivery in her new location with no appreciable delay and no alleged damage. For the remainder of the alleged orders or deliveries, plaintiff failed to sufficiently identify them, or assert that defendants either actually interfered with them or were not lawfully authorized to do so by the seizure order. Thus, Supreme Court properly dismissed the cause of action sounding in trespass to chattels or conversion. Accordingly, the court properly dismissed the entire complaint.

* Andrew Sellars, Twenty Years of Web Scraping and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 24 B.U. J. Sci. & Tech. L. 372 (2018). The abstract:

“Web scraping” is a ubiquitous technique for extracting data from the World Wide Web, done through a computer script that will send tailored queries to websites to retrieve specific pieces of content. The technique has proliferated under the ever-expanding shadow of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), which, among other things, prohibits obtaining information from a computer by accessing the computer without authorization or exceeding one’s authorized access. Unsurprisingly, many litigants have now turned to the CFAA in attempt to police against unwanted web scraping. Yet despite the rise in both web scraping and lawsuits about web scraping, practical advice about the legality of web scraping is hard to come by, and rarely extends beyond a rough combination of “try not to get caught” and “talk to a lawyer.” Most often the legal status of scraping is characterized as something just shy of unknowable, or a matter entirely left to the whims of courts, plaintiffs, or prosecutors. Uncertainty does indeed exist in the caselaw, and may stem in part from how courts approach the act of web scraping on a technical level. In the way that courts describe the act of web scraping, they misstate some of the qualities of scraping to suggest that the technique is inherently more invasive or burdensome. The first goal of this piece is to clarify how web scrapers operate, and explain why one should not think of web scraping as being inherently more burdensome or invasive than humans browsing the web. The second goal of this piece is to more fully articulate how courts approach the all-important question of whether a web scraper accesses a website without authorization under the CFAA. I aim to suggest here that there is a fair amount of madness in the caselaw, but not without some method. Specifically, this piece breaks down the twenty years of web scraping litigation (and the sixty-one opinions that this litigation has generated) into four rough phases of thinking around the critical access question. The first runs through the first decade of scraping litigation, and is marked with cases that adopt an expansive interpretation of the CFAA, with the potential to extend to all scrapers so long as a website can point to some mechanism that signaled access was unauthorized. The second, starting in the late 2000s, was marked by a narrowing of the CFAA and a focus more on the code-based controls of scraping, a move that tended to benefit scrapers. In the third phase courts have receded back to a broad view of the CFAA, brought about by the development of a “revocation” theory of unauthorized access. And most recently, spurred in part by the same policy concerns that led courts to initially constrain the CFAA in the first place, courts have begun to rethink this result. The conclusion of this piece identifies the broader questions about the CFAA and web scraping that courts must contend with in order to bring more harmony and comprehension to this area of law. They include how to deal with conflicting instructions on authorization coming different channels on the same website, how the analysis should interact with existing technical protocols that regulate web scraping, including the Robots Exclusion Standard, and what other factors beyond the wishes of the website host should govern application of the CFAA to unwanted web scraping.

Contracts

* Thomas v. Facebook, Inc., 2018 WL 3915585 (E.D. Cal. Aug. 15, 2018):

Plaintiff has not satisfied her “heavy burden” of showing that the forum selection clause in Facebook’s SRR was fraudulent or overreaching, that its enforcement would deprive her of day in court, that it contravenes public policy, or that it otherwise does not comport with fundamental fairness. On the contrary, Plaintiff offers no explanation for why this Court should not enforce the forum selection clause contained in Facebook’s SRR, nor is the Court aware of any legal reason why that clause should not be enforced.

* Biltz v. Google, Inc., 2018 WL 3340567 (D. Hawaii July 6, 2018).

In a transparent effort to evade the contractual forum selection clause that he acknowledges binds him, Brian Evans has enlisted the aid of his colleague, Mark Biltz, to stand in his shoes as Plaintiff. According to Biltz, he is not bound to litigate this action in Santa Clara County, California because unlike Evans, he did not agree to the YouTube Terms of Service agreement or Google’s advertising program’s terms, and his claims are, in any event, based on an oral, not written, contract that has no forum selection provisions.

The evident gamesmanship gets Biltz (and Evans) nowhere. The gravamen of this action is that Google owes Biltz unpaid royalties for an internet video entitled, “At Fenway,” that Biltz produced, Evans starred in, and which Evans uploaded to Google’s YouTube platform in March 2013. There is no dispute that the YouTube Terms of Service agreement in effect now, and then, requires any claim arising out of YouTube’s services to be brought in Santa Clara County, California. Whether the agreement’s signator was Evans, Biltz, both, or neither, it matters not. They could not have availed themselves of YouTube’s services without subjecting themselves to the same terms of service as every other user. The claims arising out of YouTube’s services, which include all of the claims here, must be brought in California.

* Daniel v. eBay, Inc., 2018 WL 3597654 (D.D.C. July 26, 2018). The court rejects eBay’s request to arbitrate the buyer’s claim over a counterfeit sale. The buyer signed up in 1999, when eBay’s user agreement didn’t have an arbitration clause but did have a unilateral amendment clause. eBay added the arbitration clause in 2012 and amended the agreement again in 2015, in both cases notifying its users about the changes. The court says the buyer didn’t get sufficient notice. Posting the new terms to the web wasn’t good enough, and a form email to all users didn’t prove that the buyer had received it. This is a troubling ruling, and I hope it doesn’t take root as precedent.

* Lopez v. Terra’s Kitchen, LLC, 2018 WL 4489588 (S.D. Cal. Sept. 19, 2018): “The Court finds that the agreement at issue in this case is a browsewrap [Eric’s comment: ugh] agreement because the consumer assents to the Terms & Conditions simply by using the website or purchasing a subscription, without visiting the Terms & Conditions page or even acknowledging that use of the website constitutes assent to the Terms & Conditions….the hyperlink to Defendant’s Terms & Conditions appears in the bottom left-hand corner of the website footer of Defendant’s webpages, below a grouping of 21 other hyperlinks, arranged in five columns, that cover topics like “Careers,” “Buy a Gift Card,” “Mediterranean Diet,” and “Newsroom.”…Here, the Terms & Conditions hyperlink is more or less buried at the bottom of Defendant’s webpage. Under Nguyen, without more, this is insufficient to give rise to inquiry notice.”

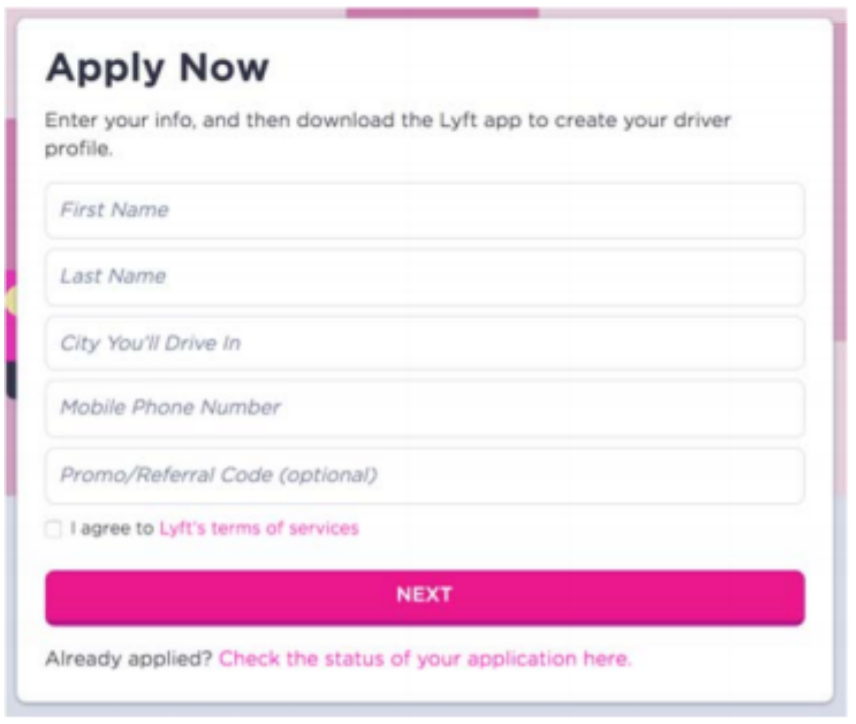

* Wickberg v. Lyft, 1:18-cv-12094-RGS (D. Mass. Dec. 19, 2018). Lyft’s TOS for drivers requires arbitration. Drivers saw the following screen as part of signing up:

Relying heavily on Cullinane v. Uber, the court deems this a “clickwrap” (ugh):

Lyft’s screen required Wickberg to click a box stating that he “agree[d] to Lyft’s terms of services” before he could continue with the registration process. And although, as Wickberg asserts, “Lyft’s terms of service” appeared towards the bottom in a smaller font and without a typical blue-colored hyperlink, the phrase was pink and distinguishable on the screen…. Wickberg affirmatively adopted those terms by clicking “I agree.”

[Personal self-congratulatory note: my Fall 2018 Internet Law final exam asked students to discuss if a pink hyperlink had the same legal effect as a blue hyperlink. 💯]

The plaintiff said he couldn’t remember clicking on the TOS. The court responds: “the relevant inquiry is not whether he actually viewed the terms but whether they were reasonably communicated to him.”

The court distinguishes two other Lyft losses based on different state law (ugh):

In Applebaum v. Lyft, Inc., a court in the Southern District of New York invalidated an online Lyft agreement because “the text is difficult to read: ‘I agree to Lyft’s Terms of Service’ is in the smallest font on the screen, dwarfed by the jumbo-sized pink ‘Next’ bar at the bottom of the screen and the bold header ‘Add Phone Number’ at the top.” Similarly, in Talbot v. Lyft, Inc., a California state court invalidated a Lyft agreement identical to the one at issue here because “nothing supports the conclusion that (i) the pink words ‘Terms of service’ were a hyperlink or that (ii) they linked to the contract that governed the working relationship between Lyft and drivers.” I find these cases unpersuasive, as they apply New York and California law, and not the law of Massachusetts.

So the court enforces the Lyft TOS and sends the case to arbitration. The correct result IMO.